The child suicide rate is low but increasing. It should be zero. The tragedy of loss is real. Schoolchildren coped with the COVID lockdown. Catch-up pressure combined with fractured families adds to the stress. Should the education system embrace holistic well-being to prevent teen suicide? Oasis Hu seeks ways society can address the crisis.

(INFOGRAPHICS: DONG KAI, MOK KWOK-CHEONG)

(INFOGRAPHICS: DONG KAI, MOK KWOK-CHEONG)

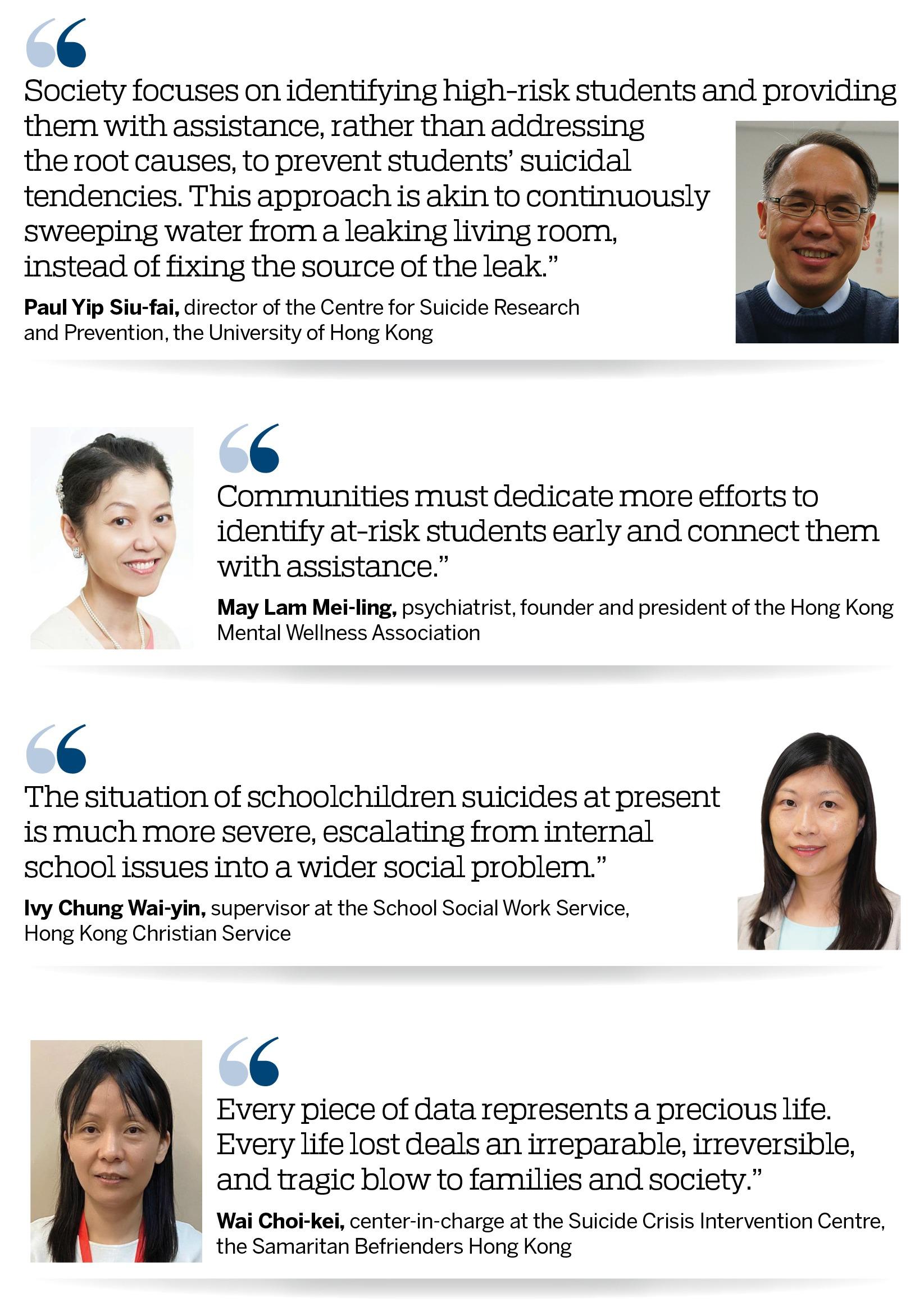

Paul Yip Siu-fai, a professor in the Department of Social Work and Social Administration and director of the Centre for Suicide Research and Prevention at the University of Hong Kong, views the data on schoolchildren suicides as a key indicator and “report card” for society, as rising suicide rates flash societal failure to address at-risk pupils.

Yip urges a shift away from obsession with academic success to more balanced interpersonal connections, to reframe student identities and guide children to find meaning in life for holistic well-being. He concedes this will require a long-term and challenging effort but the change can no longer wait. The alarming increase in suicide cases among schoolchildren in Hong Kong demands immediate attention.

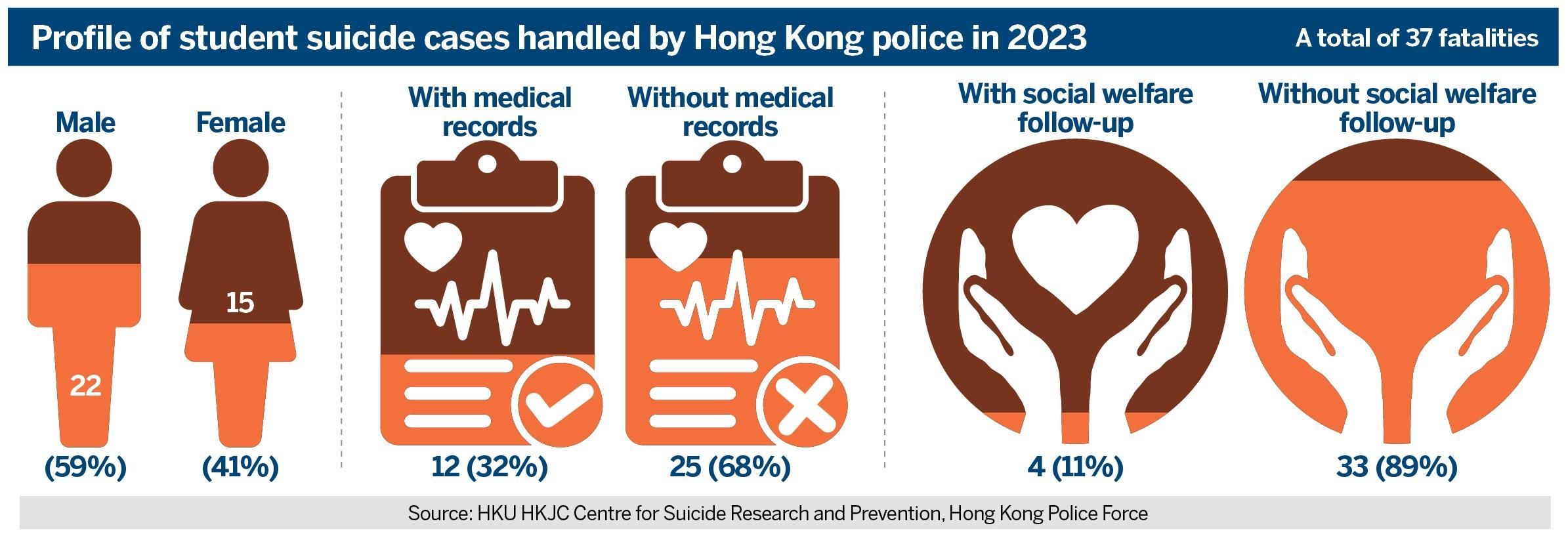

Police data revealed that, as of November, 306 schoolchildren attempted suicide, with 37 fatalities at an average age of 16.3 years old, and 15.7 years old for the 269 who survived. The numbers indicate teenagers as the most vulnerable group.

Early detection

The Hong Kong Special Administrative Region government implemented a Three-Tier School-based Emergency Mechanism in secondary schools from December last year to January this year for early identification of at-risk students, establishing off-campus support networks, and referring severe cases to the Hospital Authority’s psychiatric specialist services.

Within this brief implementation, principals made 30 referrals to the Hospital Authority. Ivy Chung Wai-yin of the School Social Work Service at the Hong Kong Christian Service says this mechanism has the potential to be effective but is concerned the impact will be limited if it has not been implemented for long enough. She is also concerned about suicide-prone students hiding their distress.

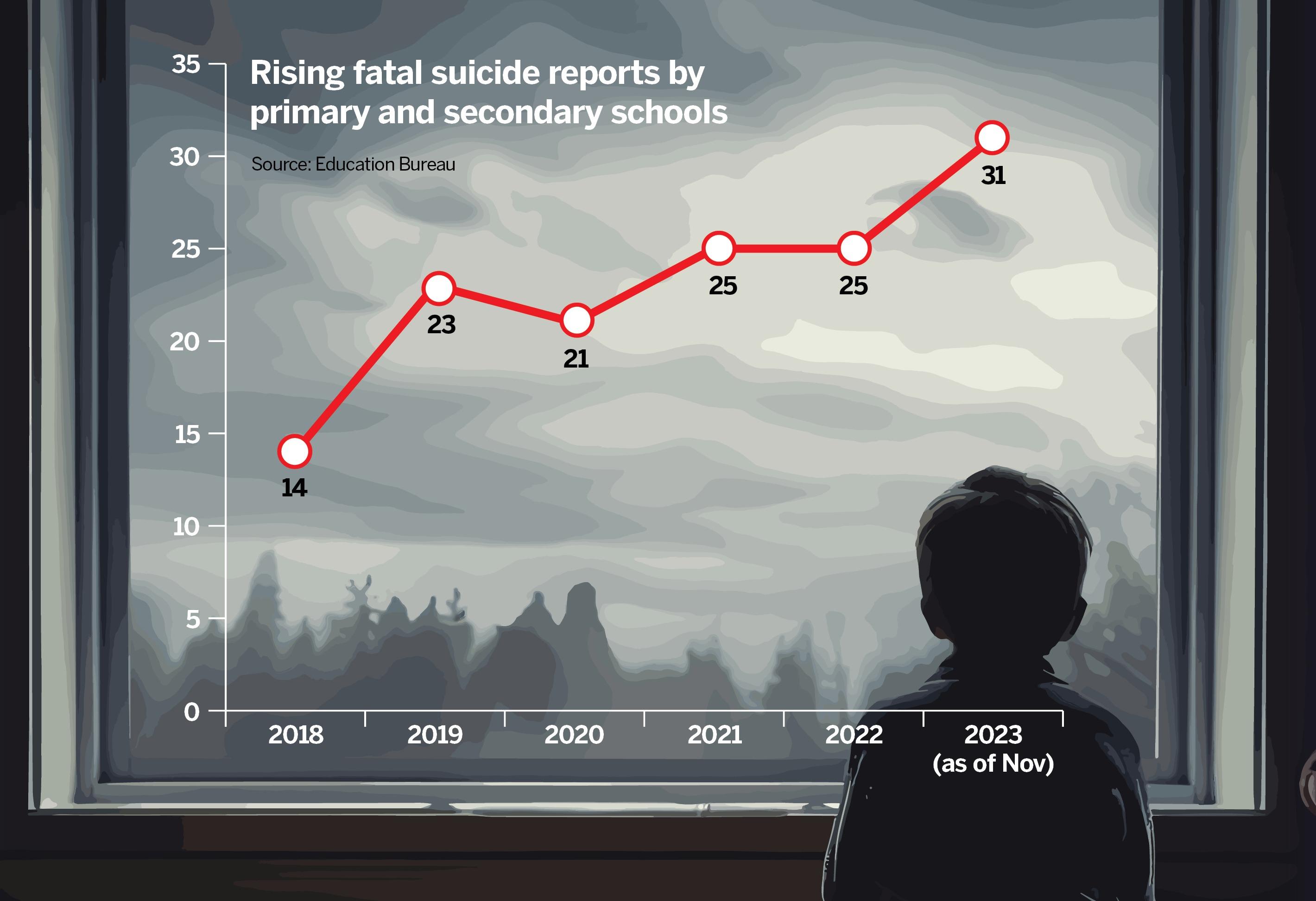

Education Bureau data also confirm an increasing trend, with primary and secondary schools’ reports of suspected suicide deaths of students increasing from 14 to 25 a year between 2018 to 2022. The figures for 2023 (post-pandemic), as of November, had reached 31 deaths — a 121 percent leap in five years.

The Samaritan Befrienders Hong Kong also reported a significant increase in the number of individuals under 19 contacting them for suicide-related help, totaling 188 cases in 2023 versus 148 in 2022, a jump of nearly 30 percent.

Chung and Phoebe Chan Hoi-man, supervisors at the School Social Work Service of the Hong Kong Christian Service, note that the increase in the number of suicides seems severe, expanding from internal school issues into a wider social problem.

Wai Choi-kei, who is responsible for the Suicide Crisis Intervention Centre at the Samaritan Befrienders Hong Kong, notes that every single piece of suicide data represents a precious life. Every life lost deals an irreparable, irreversible, and tragic blow to families and society.

Gender differences

Out of the 306 suicide-related cases in 2023, 217 were female, while 89 were male. Of these, 269 were attempted suicides, with a gender split of 202 females and 67 males. Of the 37 fatalities, 22 were males and 15 females.

Yip observes that women are more likely to survive suicide attempts as they opt to use less lethal means, while men exhibit a greater determination to follow through once they decide to end their lives.

May Lam Mei-ling, psychiatrist and founder and president of the Hong Kong Mental Wellness Association, says that while some attempted suicide cases are prevented, there is a continuing risk of repeated suicide attempts within this group. Lam advocates priority support for them.

Wai, suicide-crisis center-in-charge at the Samaritan Befrienders Hong Kong, says that in 2023, cases contacting them for suicide-related help rose sharply over 2022 among younger schoolchildren — up 36.3 percent for 13-year-olds, 45.5 percent for 12-year-olds and 87.5 percent for 11-year-olds. Of the 118 cases in 2023 at her center, the youngest was only six years old, exclaims Wai.

Matrix of causes

Chung and Chan, supervisors at the School Social Work Service of the Hong Kong Christian Service, conducted 150 interviews with schoolchildren in November to survey reasons for suicide. Academic stress at 72.7 percent ranked foremost, with family relationship issues second at 48 percent. Interpersonal relationship difficulties followed at 26 percent.

Chan notes that the factors contributing to suicide cases are often a multifaceted and interconnected matrix. It is common for vulnerable individuals to experience multiple stress points simultaneously, leading to an overwhelming loss of hope.

Chan says that suicide tendencies intensify when students return to school following long breaks — in the months after summer recess, winter holidays, Chinese New Year, and Christmas. Police data also found clustering of suicide cases and outreach for help in May and October. Post-COVID, normalized schooling, which resumed in 2023, added complications to students’ lives as well.

Chan notes that students experienced enormous academic pressure trying to catch up after almost three years of lockdown. This academic burden weighed especially on pupils sitting for the pivotal Hong Kong Diploma of Secondary Education examination. No allowance for the pandemic factor was made for students sitting the HKDSE exam. Extracurricular activities, tutorials and special interest classes returned to full swing, adding to the overall burden, says Chan.

Chan’s colleague Chung notes that extensive changes to Hong Kong’s entire education system over the past four years have made it harder for both teachers and students to adapt. Some institutions saw about 15 to 18 teachers leaving the profession during the pandemic, disrupting several schools. In the scramble to replace teachers, emotional care for students lost priority in the affected schools, observes Chung.

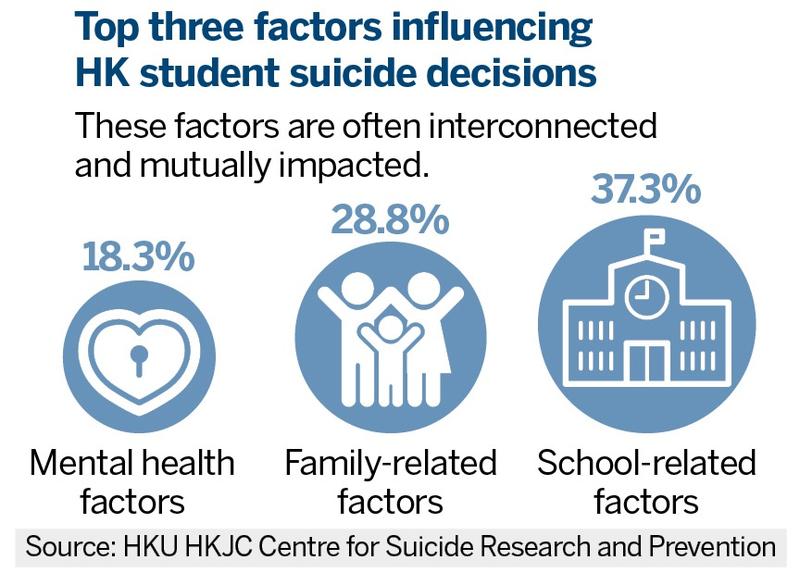

The 306 suicide-related cases in 2023 highlighted that the school environment was a contributing factor, accounting for 37.3 percent of student suicide cases, for reasons including difficulties in adapting to academic progress, bullying issues, and the pressure of examinations, etc.

Family factors contributed to 28.8 percent of suicides. Wai of the Samaritan Befrienders, says that fractured family settings, such as divorced or separated parents, domestic violence, unemployed parents, etc, added to student stress. Dysfunctional families remove a critical home support factor for students already disadvantaged at school.

Busy work schedules deprived parents of time and attention for children, leading to a lack of emotional security and well-being. They may also adopt an overly strict and performance-oriented approach, prioritizing academic results over their children’s emotional needs, further exacerbating anxiety, says Wai.

Psychiatric counseling

Police data revealed that among 37 suicide cases, mental health factors, such as depression, agitation, etc, accounted for 18.3 percent of the causes. The Samaritan Befrienders’ Wai notes that mental illnesses can stem from predispositions like pessimistic temperaments or physiological factors, or be triggered by traumatic shocks. Hong Kong has consistently reported elevated mental illness prevalence, with one study in November finding nearly 25 percent of youth grappling with at least one mental health condition.

Yip points out that among the 37 cases, only 12, or approximately 30 percent, had medical records indicating any pre-existing illness or mental health condition. For the remaining 70 percent of cases without medical records, it is challenging to determine whether they had illnesses, or undisclosed mental health conditions, or if they did not have any illnesses at all. Yip’s point is that student suicide is prompted not only by mental illness, and should not be overmedicalized. To effectively address the problem requires a holistic approach beyond just students’ mental condition.

Lam of the Mental Wellness Association says most international scientific research papers declared 90 percent of suicide cases experienced at least one mental disorder. She argues that it is highly likely that most schoolchildren who commit suicide have underlying psychiatric issues. She therefore advocates a community-approach to identify at-risk students early and connect them to professional help and emotional care to prevent suicides.

Among the 37 suicides in 2023, only four cases had social welfare care, reflecting the low detection rate of students at risk of suicide. Lam says warning signals precede some suicides, such as sudden and abnormal changes in behavior, avoiding school, dropping out of activities, opting not to interact socially, neglecting personal grooming, etc.

These signals were easier to detect before the pandemic, as teachers, classmates and friends could readily notice when someone was unhappy. However, during the pandemic, with reduced contact between students and teachers, lockdowns, emigration of friends, teacher resignations, etc, these signals went unnoticed, Lam says.

Chung at the School Social Work Service of the Hong Kong Christian Service mentions that of the six suicide cases the center handled, only one student had been monitored by a social worker. The remaining five displayed no noticeable abnormalities in their daily lives, with one seemingly having a good time at school the day before suicide. Chung says it was hard to identify suicide-risk students if they deliberately conceal their problems.

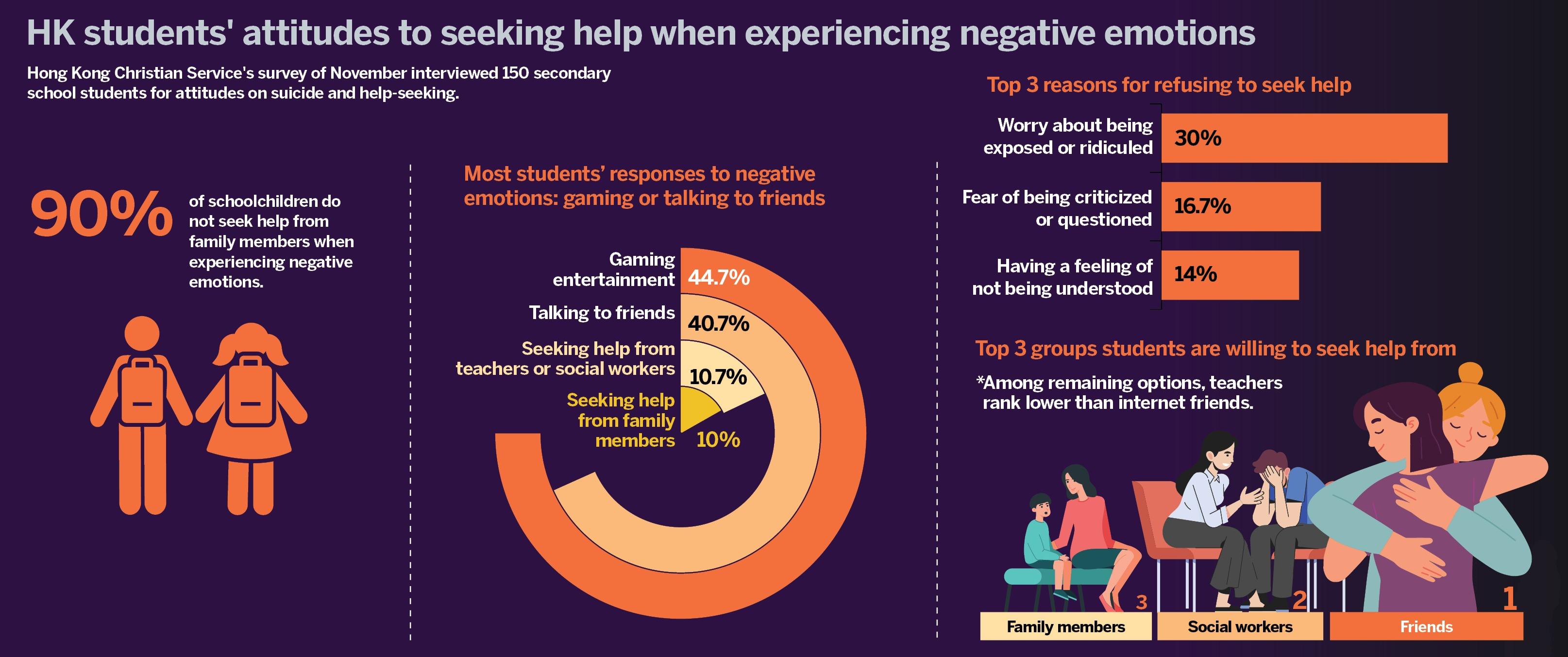

Could fellow students be a source of identification? Research shows that the majority of schoolchildren do not confide in others when facing negative emotions, as they fear “spreading or being ridiculed” (30 percent), “being criticized or questioned” (16.7 percent), or “not being understood” (14 percent).

Coping behaviors under stress include resorting to gaming and entertainment (44.7 percent), and confiding in friends (40.7 percent). Only about 20 percent seek help from teachers, social workers and family members, and when they do, they rank social workers, family members and teachers in descending order. Among remaining options, teachers rank lower than internet friends.

Global challenge

Direct comparisons across regions are problematic due to different data collection methods, but statistics generally indicate teenage suicide trending upward across the world.

In Taiwan, suicide mortality climbed sharply from 0.4 to 1.6 per 100,000 for 10- to 14-year-olds and from 4.1 to 5.4 for 15- to 19-year-olds between 2017 and 2022. The Chinese mainland records rose from 0.96 to 1.7 and 1.4 to 3.34 within similar age brackets over this period. Singapore reported more than tripling of cases among 10- to 19-year-olds, advancing from 12 in 2017 to 34 by 2022.

Data from England and Wales showed the 15-19 age group’s suicide rate up from 5.4 to 6.3 between 2017 and 2021. In the United States, suicide was the second and third leading cause of death for those aged 10-14 and 15-24 respectively in 2020.

Yip says that the causes of suicide may differ across regions, but the available data indicates that adolescent suicide has emerged as a pressing global challenge. Young people nowadays are exposed to a multitude of distressing factors, including fractured families, unemployment, poverty, pandemics, climate change, intense competition, negative social media, etc.

Yip emphasizes that as teenagers progress from a state of depression and unhappiness to contemplating suicide and formulating a suicide plan, they undergo crucial psychological shifts in helplessness and hopelessness. Unfortunately, the prevailing societal framework fails to offer young people enough hope and help.

Community effort

Wai of the Samaritan Befrienders says recognizing potential suicide signs should not be limited to professionals. Parents, teachers, and classmates can all play a role, but society must first offer them the required emotional education, coaching, and mental health awareness.

Students may exhibit abnormalities in physical, behavioral, emotional, and mental aspects, notes Wai. For example, physically, they may suffer headaches, insomnia, or stomach pain. Behaviorally, there may be a sudden decline in grades or a reluctance to socialize. Emotionally, they may exhibit depression and sadness. Mentally, they may harbor negative thoughts.

When noticing these signs, parents, teachers, and friends must prioritize the emotional well-being of students. When students consistently fail to complete homework, a teacher might investigate emotional stress, instead of readily disciplining the pupil, suggests Wai.

Christian Services’ Chung calls for society to combat the stigmatization of mental health issues and eliminate the shame around help-seeking, empowering youth to openly discuss distress without fear of judgment. Also, since students often confide their problems only to those to whom they are closest and whom they trust, society must foster closer relationships and connections within communities and schools.

Addressing root causes

HKU’s Yip suggests we go beyond identifying high-risk students and providing them with assistance. Society should address the root causes of youth anguish to prevent students’ suicidal tendencies. “Our approach is akin to continuously sweeping water from a leaking living room instead of fixing the source of the leak,” says Yip.

Yip emphasizes that the high suicide rate is a warning and a reflection of society as a whole. It compels us to introspect about why students reach such desperation to end their life, and what causes such profound unhappiness? Society must promptly take action to instill hope in young people, says Yip. Corrective actions can reduce stress in schools, create more opportunities for students with lower academic results, and offer life and emotional growth counseling.

Parents and teachers need coaching about teen stress and early suicide detection. Within families, parents should offer effective care, provide high-quality companionship, avoid harsh criticism, and learn better ways to interact with teenagers.

Yip explains that society needs to review its conventional measures of success and embrace a more inclusive and flexible educational philosophy. Redefining success, prioritizing holistic development and joyful learning for students are crucial. Success should not be limited to degrees, grades, or high-paying jobs, at the expense of the well-being of students. Although this transformation takes time, it is vital to begin now, he says.

What's next

Society: Redefine success, prioritize holistic development, value students’ well-being.

Schools: Make learning joyful, offer mental health education, create growth paths for all students.

Parents: Monitor children’s emotional changes, foster open communication, provide companionship, avoid harsh criticism.

Individuals: Note abnormal behavior, be alert to distress and suicide plans, seek help.

Contact the writer at oasishu@chinadailyhk.com