More than six decades after the local government erected its first disaster relief housing blocks, the gap between HK’s private and public housing seems to be narrowing. Rebecca Lo reports.

Mei Ho House is Hong Kong’s last remaining example of a Mark I building in a single-block configuration. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Mei Ho House is Hong Kong’s last remaining example of a Mark I building in a single-block configuration. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

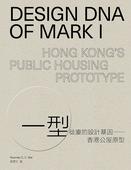

On a sunny morning in late 2019, the basement auditorium in Hong Kong Museum of Art was packed with architects, students, civil servants and museumgoers interested in learning about public housing. They were attending the first event held at the renovated venue: a conversation between professors Rosman Wai and Lee Ho-yin of the University of Hong Kong’s Division of Architectural Conservation Programmes. The talk centered around Wai’s book, Design DNA of Mark I: Hong Kong’s Public Housing Prototype.

It was fitting that an art museum’s first public forum opened with a talk about public housing architecture, as architecture has long been considered a functional art. Wai’s long career as a senior architect with Hong Kong Housing Authority and personal fascination with public housing typology led to a quest to uncover its roots, culminating in the publication of Design DNA of Mark I.

The local government’s response to the 1953 Christmas Day fire that left 53,000 people in Shek Kip Mei homeless had resulted in one of the world’s most successful public housing programs. Today, 3.3 million people — roughly 45 percent of Hong Kong’s population — live in public housing. It takes five years on an average to get past a queue of approximately 270,000 applicants waiting at any given point in time to secure a flat in public housing, making the distribution system a frequent target of criticism. Yet, it can be argued that the government — the city’s biggest landlord and developer — has done more toward sheltering its residents than many private developers.

Manfred Yuen of Groundwork Architect likes adapting old public housing structures to create co-living facilities. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Manfred Yuen of Groundwork Architect likes adapting old public housing structures to create co-living facilities. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Community bonding

Interior designer Walter Li was born and bred in public housing. “My earliest memory was living with my six siblings and parents in a Mark I estate,” Li says. “My parents are from Chaozhou. There was no work after the war, so they sought better opportunities in Hong Kong.”

Upon arrival in Hong Kong, the couple lived in a shanty in the hills of Kowloon for eight years before qualifying for three 120 sq ft units in the now demolished Jordan Valley Public Housing. The family eventually moved to a trident-style estate nearby in Choi Ha. After Li returned to Hong Kong in 2016 following 15 years of living and working in Shanghai, he began sharing a one-bedroom public housing unit with his brother in Sheung Shui.

Architect-academic Rosman Wai notes the Hong Kong Housing Authority was a pioneer in replacing cement with more sustainable options. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Architect-academic Rosman Wai notes the Hong Kong Housing Authority was a pioneer in replacing cement with more sustainable options. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Li has fond memories of his childhood. “We were a very close community,” he recalls. “Unit doors were always open. If my mother ran out of salt for the evening meal, there was always someone willing to share since everyone cooked in the open corridors outside their units. There were always kids to play with. In the 360 sq ft that we were allocated, my parents divided a room for themselves and a room for my sisters. We boys slept on the floor on boards, which were folded up during the day so we could eat together or do homework.”

Wai feels that memories of Mark I and subsequent public housing estates from the 60s and 70s have a lot to do with nostalgia. People today have different living habits and seek different things from their homes. “The community aspect of public housing estates was the result of the situation at that time,” she believes. “All the people living there had similar economic circumstances. They helped each other out. The purpose of communal facilities, such as toilets and water sources, was to cut costs.”

The community bonding between people living in Mark I public housing in the 60s and 70s was remarkable. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

The community bonding between people living in Mark I public housing in the 60s and 70s was remarkable. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Ahead of the curve

As public housing design progressed from disaster relief to communities based on new town concepts such as Wah Fu Estate in Pok Fu Lam, more attention was paid to planned public amenities such as on-site schools, banks and markets. Units were designed with private kitchens and bathrooms, and plenty of natural light and air. Many can accommodate wheelchair access, allowing for residents to grow old in their homes with ease.

“The Housing Department was the first developer in Hong Kong to pre-fabricate entire kitchens and bathrooms off site,” Wai notes. “It began replacing cement with more sustainable options. During SARS, the government discovered that U-traps were possible sources of contamination if they dried out, and began changing this in the new estates that were built later. The government has the resources to ensure that criteria for barrier-free design and good building practices can be implemented.”

The common areas in present-day co-living facilities are a throwback to those in public housing built decades ago. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

The common areas in present-day co-living facilities are a throwback to those in public housing built decades ago. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Hong Kong and Shenzhen-based Manfred Yuen of Groundwork Architect has noticed that while public developments are improving in space, function and amenities, the space within individual units of newer private development projects seems to be shrinking. The designer of Oootopia co-living spaces strives to instil clever and beautiful furnishings even in limited square footage. He prefers working with older buildings, such as the ones he designed for Oootopia in Kai Tak and Tai Kok Tsui: “Older private estates paid more attention to climate control, mostly because air-conditioning was a novelty. They encourage humans to live with nature. I find it extremely disturbing when I see windowless rooms for helpers, which is simply inhumane.”

He feels that offering lavish shared spaces as sweeteners is the wrong move. “You simply cannot substitute private spaces with clubhouses, which has been the narrative for private developers over the last two decades,” Yuen argues. “Let us simply listen to our own inner voices: Families need balconies. Our homes are where we can be ourselves, manifest our desires and hide our wealth. Homes are destinations after a hard day of work, and there are very few substitutes. Clubhouses and their affiliated landscapes, no matter how well-designed, do not replace homes. In short, if you tear the thin veneer of glam from most new real estate residences in Hong Kong, you will find very little difference between private and public housing.”

A typical interior layout in public housing units of the past displayed in the Mei Ho House museum. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

A typical interior layout in public housing units of the past displayed in the Mei Ho House museum. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Comfort zone

Wai acknowledges that while some recent units in private estates are smaller than public ones, there is nevertheless a wider range of homes to choose from. “Public housing provisions suit their users’ needs,” she comments. “In private estates, the exterior tends to be impressive and lobbies generally are bigger. The building is often a brand. Inside, though, public housing units are just as functional and efficient as private ones due to the research put into making them work.”

Li prefers living in public housing, despite his job opening a world of lifestyle options to him in the private realm. “There is no need to spend any money on maintenance in public housing rentals,” he notes. “Of course, the materials are fancier in private housing. There are typically fewer units per floor, allowing for more exclusivity. But private housing units are getting smaller and smaller — some of the newest ones are smaller than public housing ones. Unless a person can purchase a really large flat, I see little benefit in buying a private housing unit since spaces are so small and values have not increased much in recent years.”

As for the nostalgia Li feels toward his childhood home, he and others who grew up in Mark I estates can revisit the past with a trip to Mei Ho House. The last original Mark I block remaining in Shek Kip Mei after redevelopment, it has been transformed into a youth hostel with a museum devoted to the evolution of Hong Kong’s public housing estates.