As space shifts from science to commerce, Hong Kong is searching for its entry point. Entrepreneurs, investors and researchers see openings in finance, leasing, high-value manufacturing — niches where the city’s strengths could matter as global competition for the space economy intensifies. Luo Weiteng reports.

Venture capitalist Ron Chiong recalls advising a British entrepreneur, currently operating from the United Arab Emirates, to consider Hong Kong for his next fundraiser.

The entrepreneur is chasing an idea that’s ambitious yet commercially grounded — converting space into tradable digital assets. His blockchain-based platform envisions trading everything from satellite spectrum and Earth-imagery data to lunar resources and space-station leases.

READ MORE: Touch base for Hong Kong’s space economy

Chiong sees the future of commerce in a most unexpected place: outer space. Tokenizing space assets is one of many commercial experiments emerging beyond Earth — the kind of innovation and investment opportunities he hopes Hong Kong could draw into its orbit. Yet for now, the center of gravity sits across the Pacific. The entrepreneur himself is fundraising in the United States where space entrepreneurship and risk-hungry capital are setting the pace.

Seeking new markets

Global space tech funding — from rocket-makers to low-Earth-orbit satellites — rallied to $3.1 billion in the second quarter of this year, with US firms securing the lion’s share with $2.2 billion. In the first half of 2025, investment in US space businesses surpassed that for the entire 2024, according to investment firm Seraphim Space. In Hong Kong, an emerging constellation of policymakers, space entrepreneurs, scrappy startups, adventurous investors and aerospace researchers are planting the seeds of what may sprout into a full-fledged space economy. It’s a grand vision that could, with time, take shape and evolve into a marketplace where companies build, launch and monetize their innovations.

Chiong has tracked the early stir. “Hong Kong’s space ecosystem is still in its infancy,” says the founder and managing partner of Perpetual Space Ventures. He sees rising awareness and an expanding calendar of gatherings across the city. Yet, much of it centers on spreading ideas and advancing science, not on building businesses.

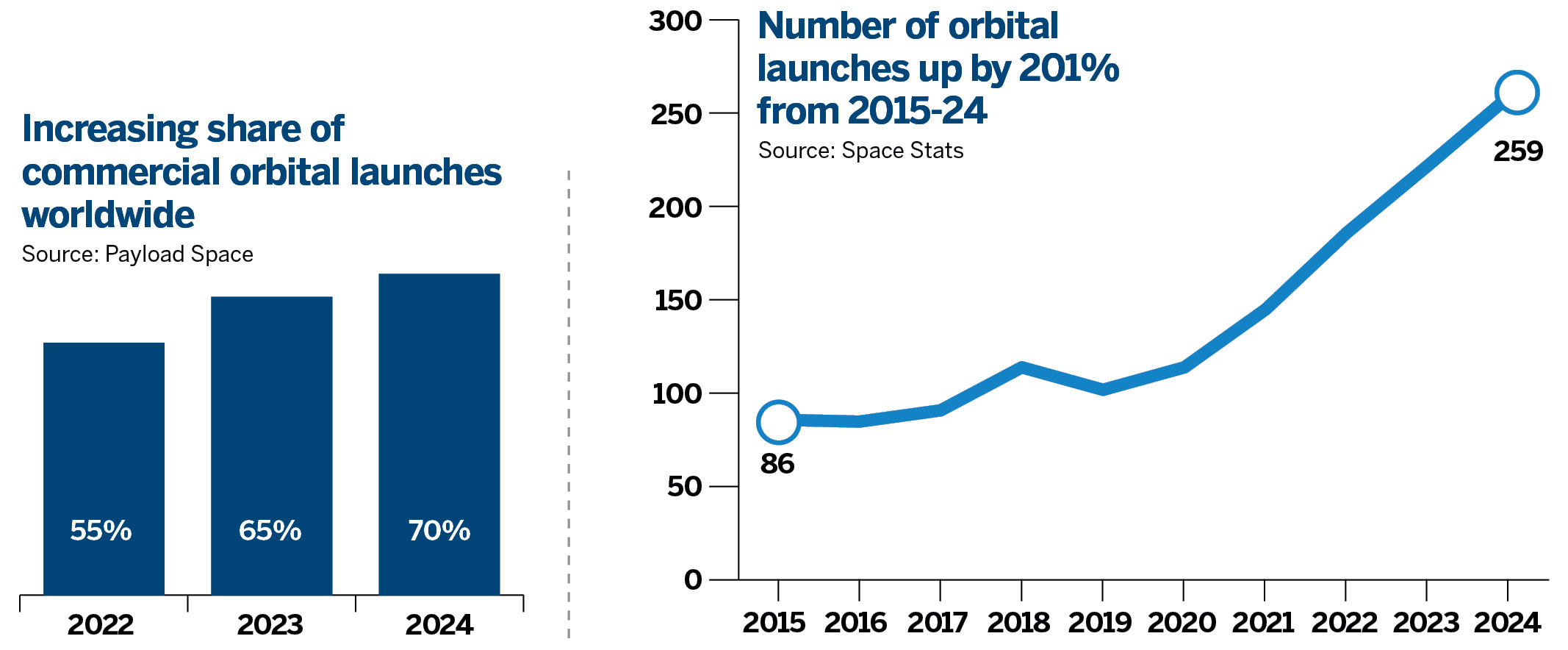

US billionaire entrepreneur Elon Musk took space commercialization to new heights in 2017 when SpaceX launched its first recycled rocket — an accomplishment he compared to finally achieving reliable aircraft rather than throwing away a functioning airplane after every flight.

Space has always been an expensive and exclusive frontier. Its economics hinge on the ability to reuse what goes up. “The success marks a big turning point that makes a new breed of space ventures possible,” says Chiong. “Think of how budget airlines democratize air travel for everyone. The bottom line is being able to reach space at a reasonable cost.”

The US leads the way, as far as reusability is concerned, with SpaceX extending the lifespan of a reused booster up to 32 flights, says Anthony Neoh who co-chairs the Asian Academy of International Law.

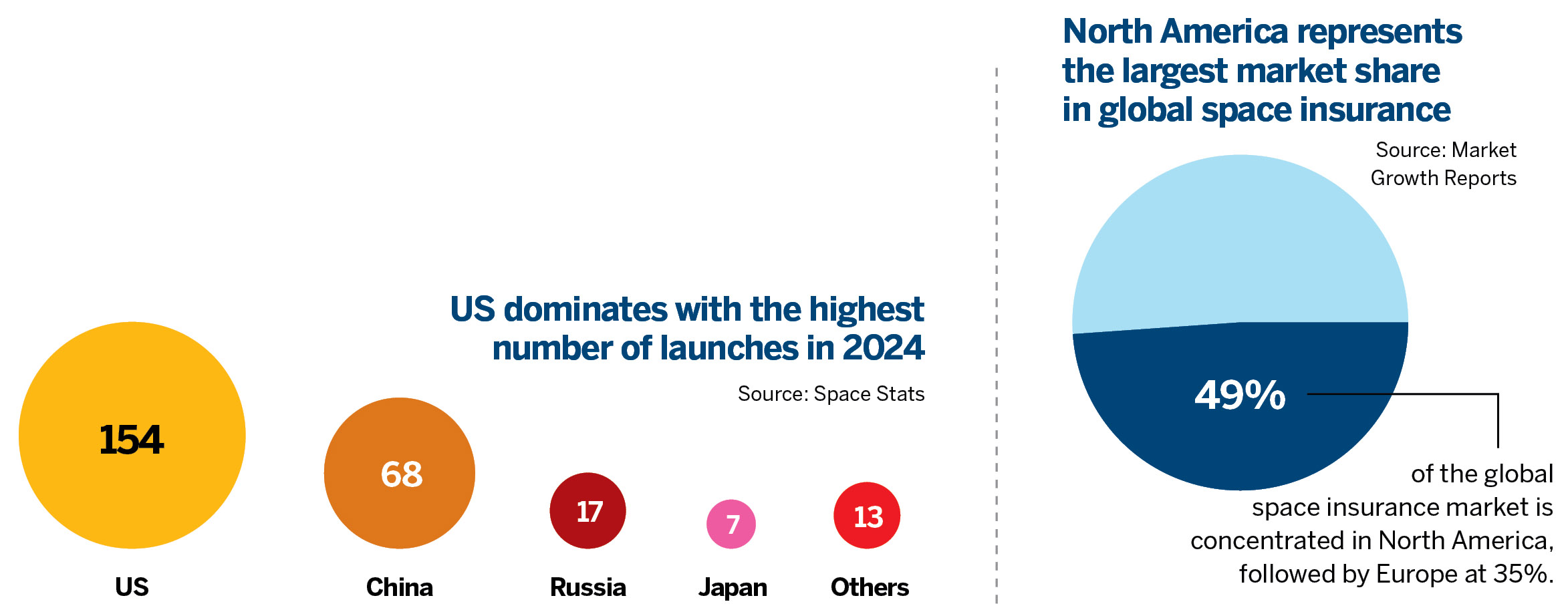

The impact is visible in launch cadence. “For every six launches by the US, China has about one,” notes Neoh.

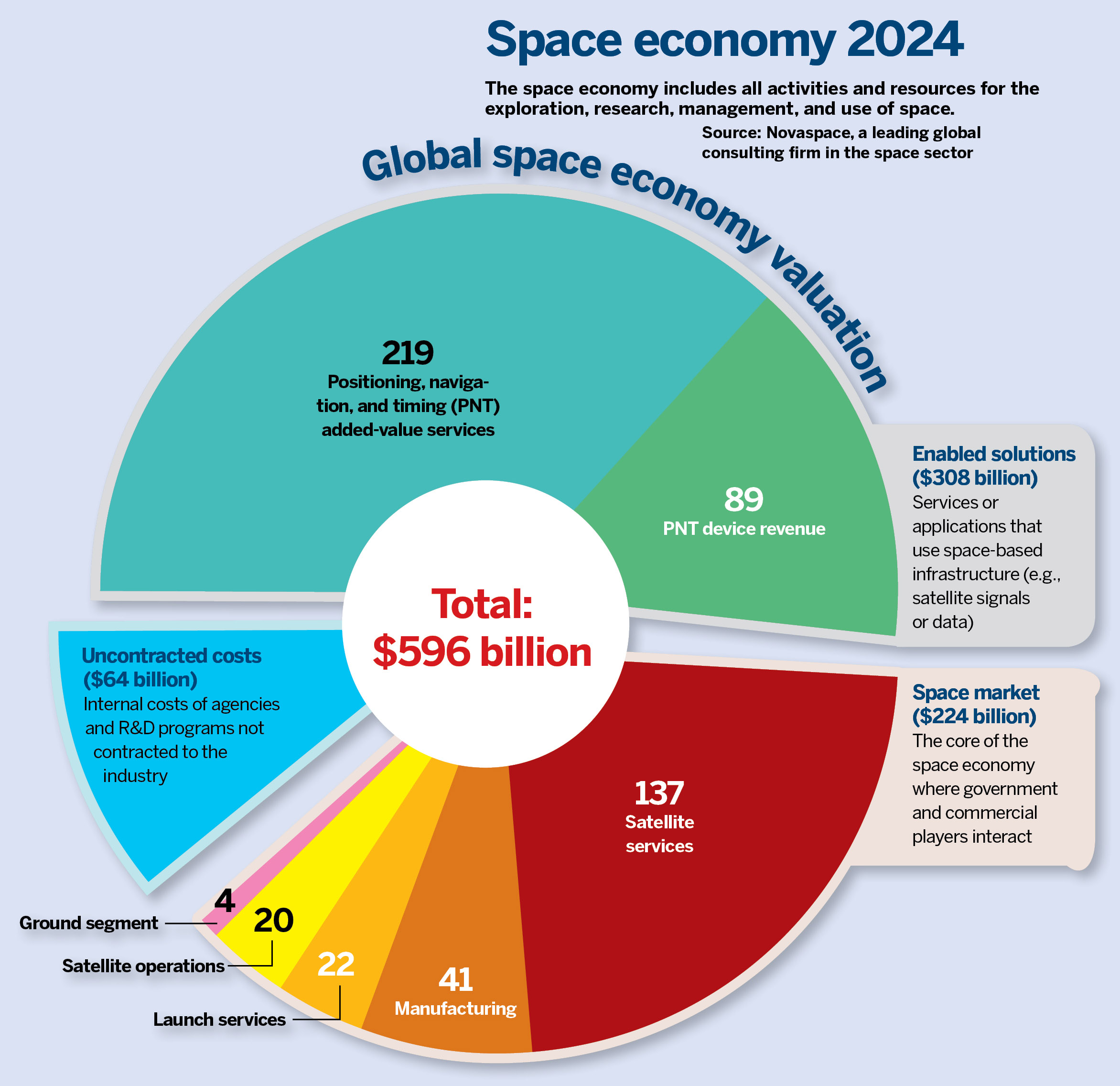

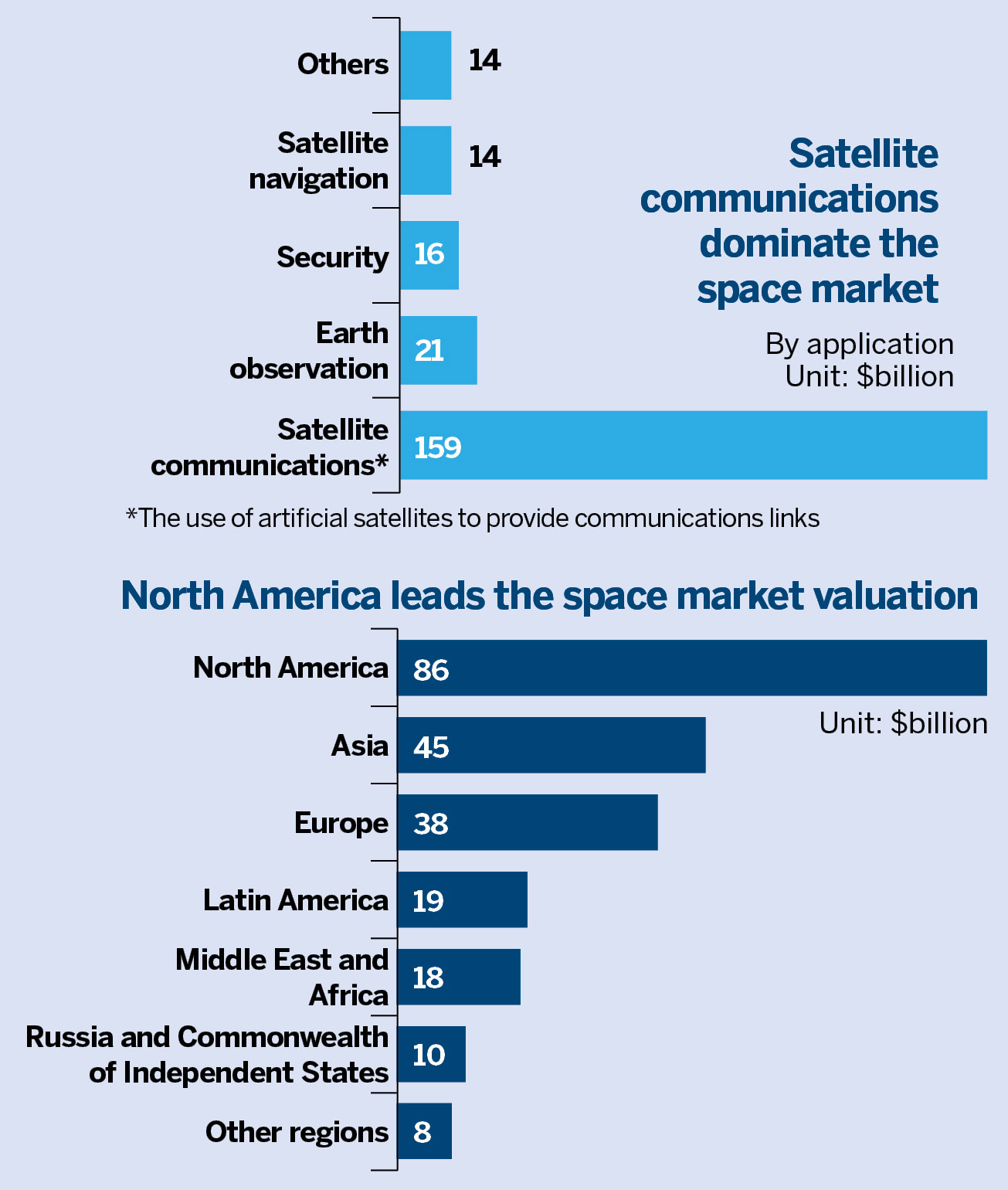

With new investors bidding up a space economy said to be worth $613 billion last year, the bulk of that is tied to the lucrative satellites business.

Again, the US leads the pack with SpaceX launching 10,501 satellites, according to US astronomer Jonathan McDowell, who tracks Starlink — the company’s constellation delivering broadband internet. As of Nov 23, there were 9,103 Starlink satellites in orbit, of which 9,088 were working.

Hong Kong is now home to four local companies actively engaged in space business. Two of them — AsiaSat and APT Satellite — operate geostationary-Earth-orbit satellites, covering 45 percent of Asia’s broadcasting services. The other two manufacture one-meter-class small satellites.

Six Chinese mainland-based firms have expanded into the special administrative region, with four of them specializing in satellite launches.

“At least two companies have completed successful trials of reusable launchers, and they should be ready for production next year,” says Neoh who formerly chaired Hong Kong’s Securities and Futures Commission.

The momentum is undeniable, but venture capital (VC) — responsible for 77 percent of global space funding in the first half of 2025 — is where commercial reality gets tested, according to VC fund, Space Capital.

Chiong says Hong Kong-based founders he has talked to often provide technical sophistication but lack commercial readiness. What they offer are engineering solutions born in university labs or business models that are still too early to scale.

“An engineering solution fixes the problem,” he explains. “A business solution fixes it and generates tangible revenue. This is one of our bottom-line requirements when investing in space tech.”

Startups that grab investors’ attention share the ingredients — a working product with technology moat, recurring income backed by government contracts, commercial operations underway or imminent, and a demonstrated rationale for fresh funding. “That’s the tipping point — the moment a space startup becomes genuinely investable,” Chiong reckons.

Commercialization is not a sidetrack, but the thread running through the entire space economy, spanning investment, financing and insurance, data collection and analytics, satellite commissioning and in-orbit servicing, as well as advanced robotics for manufacturing, among other domains. Last year, the commercial sector accounted for 78 percent of the global space economy, according to the US-based Space Foundation.

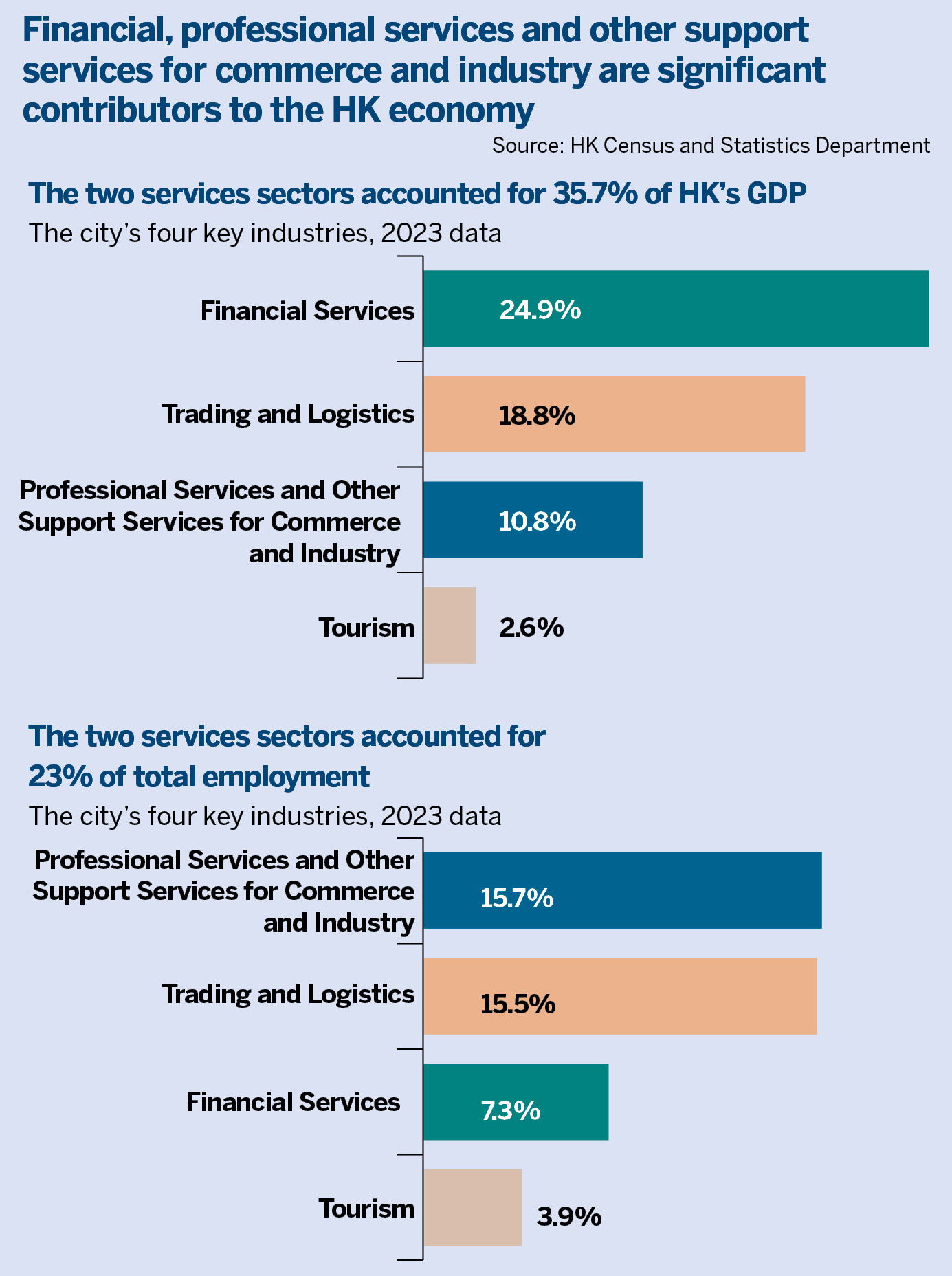

Hong Kong’s location on this ladder lies in what the city knows best — finance — says Dewey Yee, professor of practice (aviation management and finance) at the Department of Logistics and Maritime Studies at the Hong Kong Polytechnic University.

Chiong agrees, calling finance and professional services the “low-hanging fruits” Hong Kong can grasp before heavier industrial groundwork is in place.

Tokenization has been floated as one possible path — a satellite operator could raise funds before the satellite is even in orbit.

Yee sets his sights on a more immediate and proven lever — leasing. “Leasing is one of the most powerful tools to unlock dormant capital,” he says. “Structurally, spacecraft leasing is the next extension of aircraft leasing, where the real difference sits in the underlying asset-backed equipment.”

As spacecraft become reusable, the logic sharpens. Engines, fairings and other capital-intensive assemblies begin to resemble durable, financeable assets, lending themselves to leasing and sparing operators hefty upfront costs.

Yee speaks from experience. Decades ago, he talked his way into Guinness Peat Aviation which is credited with kick-starting Ireland’s aircraft-leasing industry. Leasing has since become the preferred option for airlines over buying globally, rising from roughly 10 percent of the total fleet in the 1970s to 58 percent at the end of 2023, according to the International Air Transport Association.

Hong Kong was a late arrival to this sphere. For all its weight in aviation financing, the city didn’t begin cultivating its leasing business until 2013. When Yee served on the Hong Kong Economic Development Commission from 2012 to 2017, he helped craft a new tax regime to entice aircraft leasing companies with competitive profit tax concessions — one that could, with modest tweaks, extend neatly to spacecraft.

Yet, the much-awaited framework remains underused as it applies only to lessors with equipment registered locally, Yee says. Ireland still dominates, backed by a mature commercial aircraft registry and generous tax depreciation allowances on aircraft assets.

That raises a broader issue — international registration of rights over aircraft and spacecraft. In 2001, the Convention on International Interests in Mobile Equipment (Cape Town Convention) and its associated Aircraft Protocol wrote the rulebook for ownership, leases, and security interests in aircraft. The Space Protocol, drafted in 2012, still awaits the 10 ratifications required to take effect — an institutional silence that Neoh sees as an opportunity.

Riding high on blockchain verification and smart contract technologies, “Hong Kong has every reason to build the world’s first commercial-grade registry of space assets,” says Neoh.

If institutions matter, so do people. Even today, aircraft leasing remains a niche. It requires a rare mix of structuring, tax planning, credit assessment and cross-jurisdictional legal judgment. Such a breadth of expertise, Yee points out, transfers naturally to spacecraft leasing where Hong Kong’s experienced leasing professionals and international lawyers could become the early architects.

For Gao Yang, director of Hong Kong Space Robotics and Energy Centre, the city’s pool of talent also gives it room to climb up the space value chain. “Hong Kong needs to play cleverly and intelligently,” she says. “High-value manufacturing is the key word.”

Embracing high value

Tomorrow’s space manufacturing won’t depend on sprawling factories or ground-based infrastructure, but on embedded artificial intelligence, robotics, and compact, lower-cost devices. As more production moves off Earth, the launch burden lightens, operating costs drop, and innovation is freed from land and scale — constraints Hong Kong has always lived with.

“You can definitely service others with finance and a legal system. But having a layer of homegrown tech as a foundation will make the whole thing more sustained,” Gao stresses.

That foundation, she argues, is where Hong Kong can carve out its niche business. Instead of squeezing into the crowded arenas of small-satellite manufacturing and Earth observation, the city is well-positioned to specialize in the higher-value, less-saturated segments — AI-defined space modules and smart in-orbit robotics components where global supply is thin, but the commercial pull is real.

The space robotics expert paints the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Greater Bay Area and Hainan province, which is home to China’s first commercial spaceport, as forming a naturally self-sustained space supply chain.

“Once you have independence, you can push into new frontiers faster and more cost-effectively,” she asserts.

This drive for self-sufficiency mirrors a global trend, as the US, China and Europe race to strengthen their domestic defense-space industries.

The US allocated $49.5 billion to defense space expenditure last year, dwarfing the combined $11.3 billion from the rest of the world. Over the past five years, non-US military space spending has soared 76.5 percent, according to the Space Foundation.

“Space always has sensitive and non-sensitive sides. The key is drawing a clear line so capital knows where to go,” Gao says.

Chiong wants that clarity. Preparing a space-tech fund focused on Southeast Asia where he finds the startup scene more coherent, the venture capitalist highlights Hong Kong’s missing piece — a space agency or office dedicated to laying out overall policy. Without it, entrepreneurs and investors would hesitate before a window of opportunities.

The window is opening rapidly. China’s commercial space sector attracted over 15 billion yuan ($2.1 billion) last year, up almost 40 percent year-on-year. For the first time, the US accounted for less than half of global space VC funding, as figures from the European Space Policy Institute show.

Chiong believes this is precisely where Hong Kong’s superconnector role matters. A one-stop coordinating body could bridge global businesses and mainland stakeholders, offering clear guidance needed to buy into the country’s race into space.

Policymakers too are warming to the idea. Veteran politician Regina Ip Lau Suk-yee has raised the issue of prioritizing the space economy with the HKSAR government, with a space industry office as the anchor.

ALSO READ: A mission of the times

Mainland space companies are already knocking on the door. Satellite company Adaspace Technology filed for a Hong Kong listing earlier this year, seeking capital, professional services and a launchpad to the world stage.

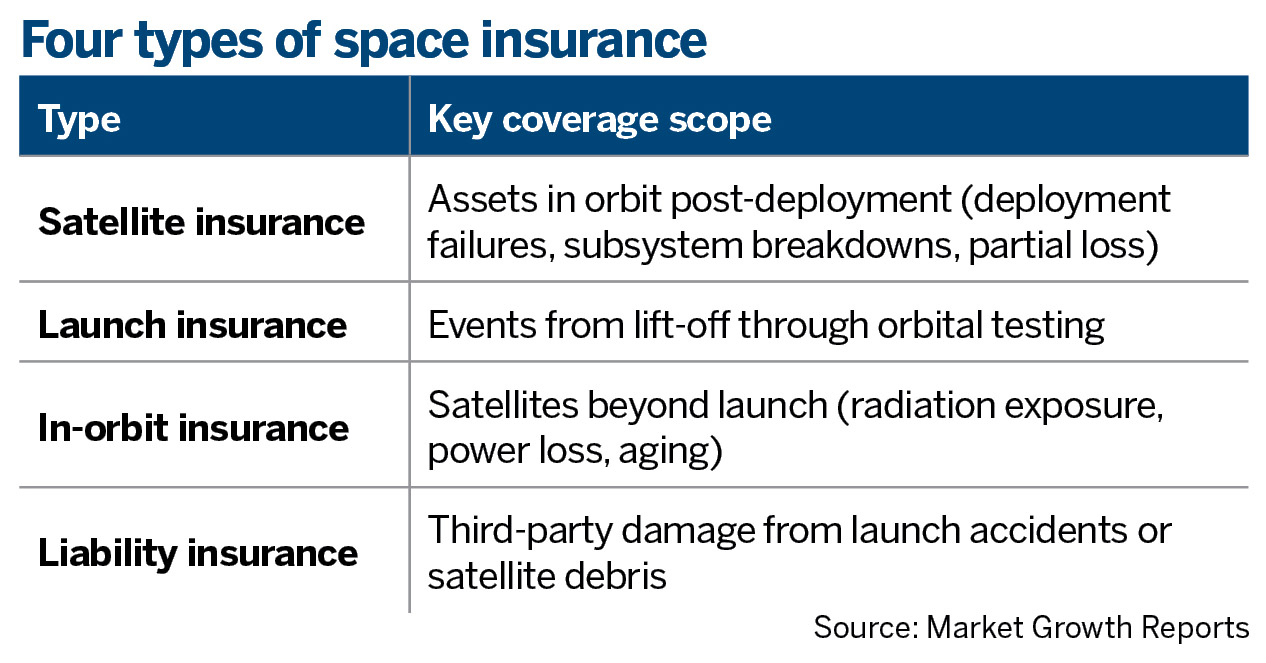

For Neoh, Hong Kong’s proximity to the mainland is its strongest commercial lever. The senior barrister recently met insurance giant Marsh McLennan’s chief executive in Beijing, who was assessing China’s vast potential in space insurance — a market long under the United Kingdom’s sway.

“As China’s space ambitions hit a new gear, the center of demand will inevitably shift,” Neoh says. The SAR’s deep bench of insurers, reinsurers, brokers and actuaries are well-placed to underwrite the future — just one example visible on the horizon.

Next Actions

- Creating one agency to unify government efforts

- Facilitating interdisciplinary collaboration

- Adopting more entrepreneurial mindsets

- Exploring public-private partnerships

- Cultivating more talent

Contact the writer at sophialuo@chinadailyhk.com