Rachel Reeves’ attempt to blame Brexit for the UK’s flagging economy risks playing down the broader causes of the country’s malaise, senior economists said.

The chancellor of the exchequer is planning to pin an expected downgrade in growth expectations by the Office for Budget Responsibility on the 2016 decision to leave the European Union and the years of austerity that preceded it. The gamble is that Brexit is an explanation voters will be likely to understand as the budget watchdog punches a multibillion pound hole in Reeves’ spending plans and forces her to raise taxes again.

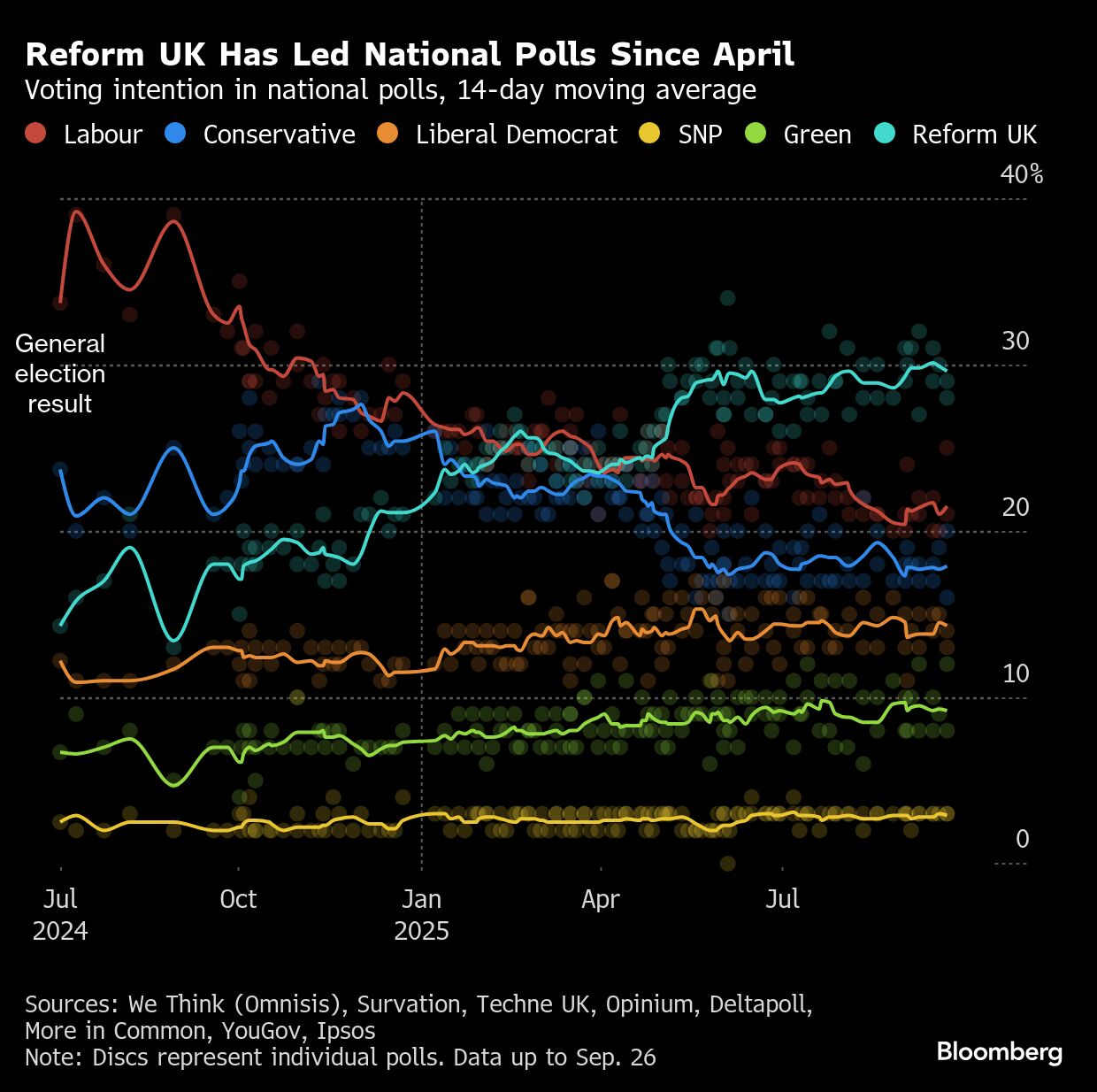

The strategy represents a shift for Prime Minister Keir Starmer, a remainer who has avoided talking about Brexit while courting leave-supporting voters who grew disillusioned with the Conservatives. It’s an approach that’s grown more attractive to the governing Labour Party as a key architect of the campaign to leave the EU, Nigel Farage, and his populist Reform UK emerge its chief rival.

The budget due Nov 26 is a moment of peril for Reeves, who vowed she wouldn’t have to come back for more after raising taxes in last year’s budget. The OBR’s expected growth cut — along with policy U-turns and the rising cost of borrowing — have left her needing as much as £35 billion ($47 billion) to close a new fiscal hole.

But economists said the chancellor’s efforts to blame Brexit are misleading because much of the slump in output per worker, which drives growth and living standards, happened before the referendum and was mirrored across the EU. The turning point was not 2010, but the 2008 global financial crisis, or even earlier, when Labour was last in power.

“We can say for certain it isn’t just Brexit,” Jonathan Portes, professor of economics at King’s College London, said. “The productivity slump has clearly not just been in the UK. Europe has been better, but not much.”

Reeves’ argument draws on analysis that shows UK productivity has undershot pre-2008 trends by about 25 percent. But Hetal Mehta, head of economic research at St James’ Place, said the UK’s productivity problems “pre-date the Brexit referendum.”

Office for National Statistics estimates published in October 2016 suggest the productivity shortfall was already 18 percent in 2015, the year before the Brexit vote.

Panmure Liberum Chief Economist Simon French, meanwhile, posted on X that while “Brexit had a role by making the UK less competitive,” it is just one factor in the downgrade along with government policies on energy, housing, pensions and post-2008 financial services regulation.

ALSO READ: Reeves risks another post-budget inflation surge, business warns

Reeves tested her argument in a Bloomberg TV interview last week, saying that the OBR used “past productivity performance to forecast the future and it is true that under the previous government over the last 14 years, both growth and productivity were underwhelming”.

In a statement to the International Monetary Fund in Washington on Friday, Reeves said separately: “The UK’s productivity challenge has been compounded by the way in which the UK left the European Union.” She repeated the claim at an investment summit on Tuesday.

The Bank of England estimates that Brexit dealt the UK a permanent 3.5 percent hit to output, not all of which has come through yet. The OBR uses a larger estimate, of 4 percent. Austerity had a smaller impact. Private analysis by the BOE in 2015 and released in 2024 showed that the Tories’ tight public spending plans and tax increases after 2010 pulled down the level of GDP by “a little over 2 percent.” Together, Brexit and austerity may have lowered productivity by 5 percent so far.

Some in the UK government are wary of Reeves leaning too heavily on the Brexit argument. There is a divide in Downing Street between a group of aides who want ministers to be more open about what they see as the costs of Brexit in an attempt to put pressure on Farage.

Others in Starmer’s team are wary of re-litigating Brexit arguments over policy areas like immigration, as Labour seeks to win back working class votes from Reform.

Rob Wood, Pantheon Macroeconomics chief UK economist, said it was “unlikely that the OBR will be able to justify a significant hit to productivity above what they have modeled to date” to explain the anticipated downgrade. “I’m not sure what evidence they could pin it on.”

While Portes said Brexit has contributed to Britain’s woes, it was only responsible for about a fifth of the 25 percent decline. The bulk of the damage was caused by “a general failure to innovate, modernize and invest,” he added. Those are “broadly common factors” that apply equally to the EU. Reeves is addressing underinvestment by increasing capital spending by £120 billion this parliament.

Andrew Bailey, governor of the Bank of England, spelled out the cost of weak productivity in a speech on Saturday, saying that if growth had remained at the pre-2008 pace of 2.5 percent a year, all else unchanged, the UK’s debt pile would now be 82 percent instead of 96 percent of GDP.

READ MORE: Sky News: UK's Reeves considering tax increases and spending cuts

Brexit will continue to drag on growth for the “foreseeable future,” he said. Weaker growth means “economic policymaking gets more difficult.”