Archaeologists uncover an additional site in Zhejiang, revealing exile, ritual and the dynasty's reluctant permanence, Yang Feiyue reports.

An hour and a half's drive southeast from the bustling heart of Hangzhou, the urban landscape gives way to a quiet, hilly terrain carpeted with tea fields.

To the untrained eye, it is merely a scenic vista in Fusheng town, Shaoxing, in eastern Zhejiang province. Yet, beneath these verdant rows lies one of the most significant archaeological secrets in southern China — the Six Mausoleums of the Song Dynasty (960-1279).

They were the final resting place of the Southern Song Dynasty (1127-1279) emperors and empresses.

The tomb cluster, now tucked away among a vast, serene landscape of green tea bushes in the town, tells a story of exile, impermanence and a profound psychological shift that shaped the final century of an empire.

In September, archaeologists uncovered a grand imperial shicangzi (stone chamber tomb) in the burial complex's northern section — the seventh such chamber discovered.

Upon entering the archaeological site, one finds Mausoleum No 7 nestled against mountains on three sides, oriented northwest to southeast, in a setting nothing short of picturesque.

The exposed stone chamber is grand in scale, covering over 100 square meters. Stone boundaries on three sides are clearly visible, while the fourth remains hidden beneath tea fields, awaiting full excavation.

"Based on the form, scale and other available data, this should be classified as an imperial-grade mausoleum," states Li Huida, deputy director of the Zhejiang provincial institute of cultural relics and archaeology and head of the Song mausoleums archaeological project.

The specifications of the stone chamber in Mausoleum No 7 are consistent with those of large stone chambers previously discovered, such as the one in Mausoleum No 1, he explains.

Archaeologists have already uncovered a long corridor on one side of the tomb, suggesting a symmetrical layout with corridors on both flanks. The courtyard-style structure extends southward into the tea fields.

The scale of Mausoleum No 7 is vast, and archaeologists believe that, above the stone burial chamber, there should have been a turtle-head hall that was designed to house and shield the top of the stone chamber from the elements. In front of it, foundations of an offering hall would have hosted rituals and worship.

Currently, a significant number of architectural remains are still preserved beneath the tea fields, Li says.

It represents a milestone that confirms half of the historically recorded "Seven Emperors and Seven Empresses" have now been located, according to the archaeological team.

The complex's origins date to 1131, when Empress Meng, widow of the Northern Song (960-1127) Emperor Zhezong, died in exile during the dynasty's frantic southward flight from the Jurchen people in the north.

She was provisionally interred at the foot of a mountain in the city's Fusheng town. This unintended event marked the founding of what would become the most concentrated royal burial ground in Jiangnan, the region along the southern bank of the lower reaches of the Yangtze River.

Seven years later, the Song court established its temporary capital in Lin'an (modern Hangzhou). Over the next 144 years, six subsequent Southern Song emperors and their empresses were buried here.

Notably, the first emperor laid to rest was Emperor Huizong, whose capture by the Jurchens led to the Northern Song's collapse. Huizong's posthumous return and burial here were a paramount concern for his son.

The site's original name, Mount Cuangong, meaning temporary palace, reflected the dynasty's enduring hope. These tombs were seen as provisional, a solemn promise that one day they would reclaim the north and rebury their ancestors in their original imperial tombs in today's central Henan province.

This is why the complex is traditionally called the "six" mausoleums, counting only the Southern Song emperors and consciously omitting Huizong, who was a Northern Song ruler, experts explain.

According to the royal ritual, an emperor's tomb was required to sit southeast and face northwest with its south side higher than the north, creating a descending slope.

Ultimately, a location northwest of Empress Meng's temporary burial site was chosen.

The discovery of the seventh chamber was no lucky accident, Li notes.

It is the fruit of a systematic, 13-year-long archaeological project by the Zhejiang cultural relics and archaeology institute.

"Ours is a long-term, continuous and meticulously planned operation," Li states.

Since 2012, his team has surveyed the entire 2.3-square-kilometer area. In 2023, they shifted focus to the northern section.

Using traditional manual drilling, they identified several promising spots, ultimately choosing the highest point for excavation as it best matched the classical royal tomb layout of "sitting against the hills and facing the water".

Li points out that the shicangzi is not merely a tomb chamber but the core of the entire burial.

It was a sophisticated, multilayered structure, beginning with a deep pit, he explains.

Then, massive stone slabs were used to construct a nested, rectangular stone casing, with gaps sealed by a type of tamped earth that hardens like concrete.

"An imperial coffin was placed within an inner, smaller stone chamber. The entire structure was then covered, and the turtle-head hall was constructed above it, serving as a protective shelter," he says.

The difference between an emperor's and an empress' tomb was most evident in the size of both the stone chamber and the aboveground architecture, he adds.

The most telling aspect of Mausoleum No 7 emerges when compared to the earlier Mausoleum No 1 from the southern section of the burial cluster.

"While the stone chambers themselves are nearly identical in size and craftsmanship — showing strict adherence to core rituals — aboveground layouts reveal a shift in mindset," Li says.

Earlier mausoleums in the south were austere: tomb, turtle-head hall, and front hall in a simple design embodying the "temporary" ethos.

By contrast, Mausoleum No 7 boasts complex flanking corridors, features previously reserved for utilitarian areas serving ancestral worship and daily management.

"This is a critical signal. It indicates that by the late Southern Song period, even though the political slogan of a temporary burial remained unchanged, the actual construction had begun to transform," he emphasizes, adding that the architecture was becoming more permanent and intricate.

"In simple terms, they probably knew in their hearts that they were never going back," Li says.

Throughout history, the Song mausoleums suffered repeated devastations, earning them the online epithet of "the most tragic imperial tombs in history". However, archaeological discoveries have gradually revealed their profound historical and cultural significance.

As Li points out, these mausoleums, together with the imperial palace, represent far more than just the lofty institutions of the royal family.

"They stand as symbols of cultural heritage involving the collective participation and creativity of society at the time," Li says.

Shou Qinze, a renowned scholar of Song Dynasty civilization and art history, highlights the long and continuous evolution of Chinese rituals, noting that a relatively complete system of ritual customs had already been established as early as the Western Zhou Dynasty (c. 11th century-771 BC).

By the Tang (618-907) and Song dynasties, a comprehensive set of ritual institutions and related cultural practices had taken shape, he says.

Over the past six centuries since the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644), the Six Mausoleums of the Song Dynasty saw a distinct sacrificial ritual system and a complete set of ceremonial norms gradually develop, which were highly valued by the descendants, Shou explains.

Despite interruptions due to various historical factors, the tradition was steadfastly maintained, making it a significant example of the enduring and unbroken transmission of Chinese civilization, he emphasizes.

Since 2012, under the overall planning of the National Cultural Heritage Administration and the Zhejiang provincial cultural heritage bureau, the Zhejiang cultural relics and archaeology institute has conducted systematic archaeological surveys, explorations and excavations at the mausoleum site.

The study of the Six Mausoleums of the Song Dynasty depends more on field evidence.

"Very few early documents have survived, and records from the Ming and Qing (1644-1911) dynasties are often highly misleading," Li says.

"Therefore, we have had to rely almost entirely on field archaeology to rediscover and understand this imperial burial ground."

Specifically, a blend of old and new methods has been applied.

ALSO READ: Accessible documentary explores China before China

"The most effective way is still traditional manual drilling and excavation — hard, meticulous work," Li admits.

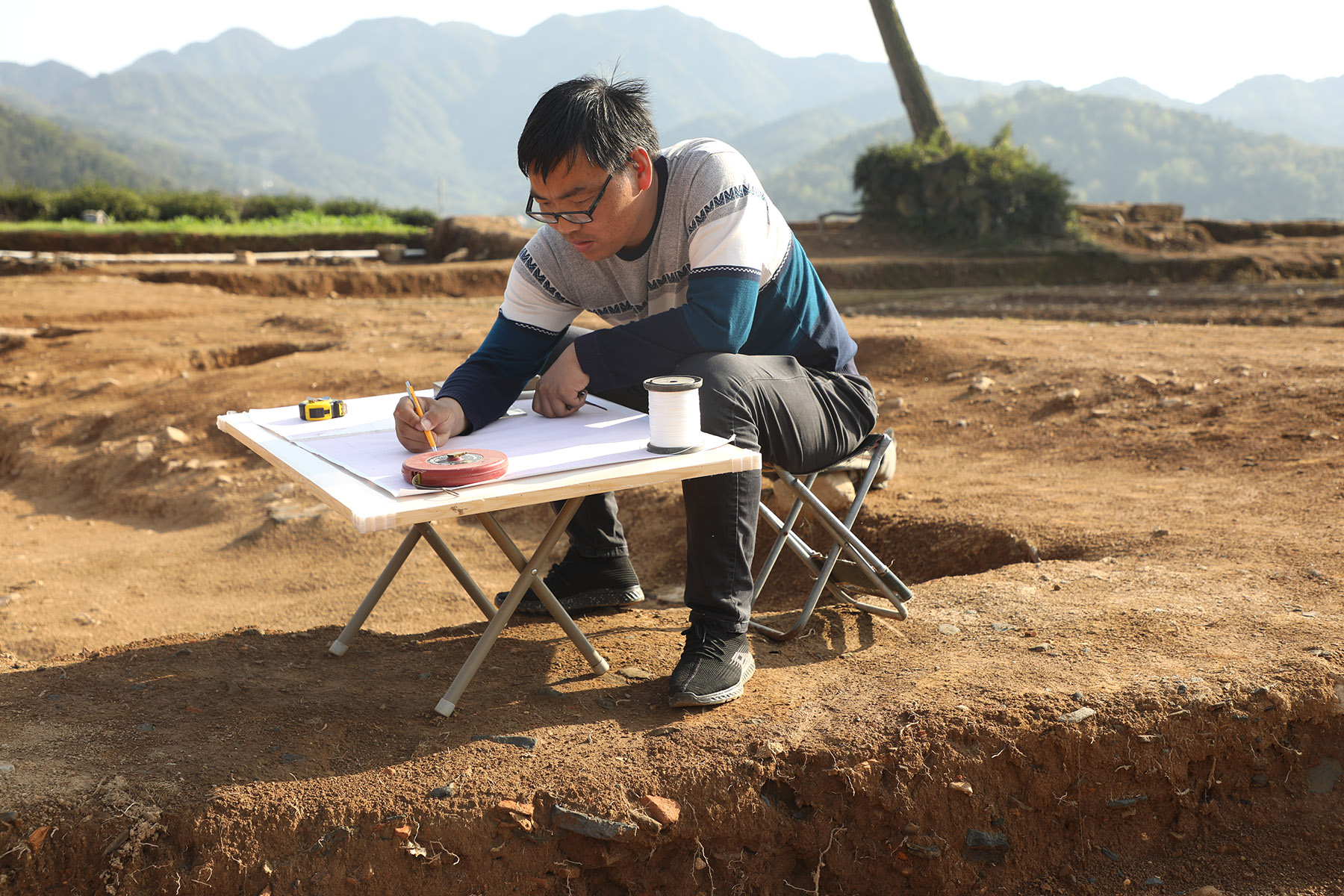

The team applied both traditional and modern methods. Manual drilling and excavation remain irreplaceable, while 3D laser scanning ensures precise recording.

Findings are expected to shape the Song mausoleums archaeological site park. Li envisions the park as both a center for protection and research, and a tourist attraction. Visitors would not only witness imperial grandeur but also learn how a mausoleum could be constructed within six to seven months and discover the communities of artisans and guards who sustained the site.

"The six Southern Song mausoleums spanned the entire dynasty. They are a perfect window into that era," Li concludes.

The discovery of Mausoleum No 7 cleans that window, offering a clearer view of a dynasty at a psychological turning point, when hopes of return gave way to a final home of stone, earth and wood.

Contact the writer at yangfeiyue@chinadaily.com.cn