A jade pendant shaped like a pepper, adorned with gilded silver leaves; a yellow-glazed snuff bottle crafted in the form of an ear of corn; and a purple clay teapot resembling a plump pumpkin — these charming objects are among the treasures on display at The World-view of the Great Ming Dynasty, an exhibition running until July 20 at the Nanjing Museum in East China's Jiangsu province.

Their inclusion is no coincidence: Pepper, corn and pumpkin were all introduced to China around the 16th century, arguably brought by the Portuguese, who then dominated maritime trade.

These exotic plants, once unfamiliar, gradually took root in Chinese soil — both literally and culturally.

Yet, long before all that, there was the legendary Chinese seafarer Zheng He, whose seven voyages between 1405 and 1433 were unmatched in scale and ambition until Vasco da Gama's historic expedition from 1497 to 1499 — more than 60 years later.

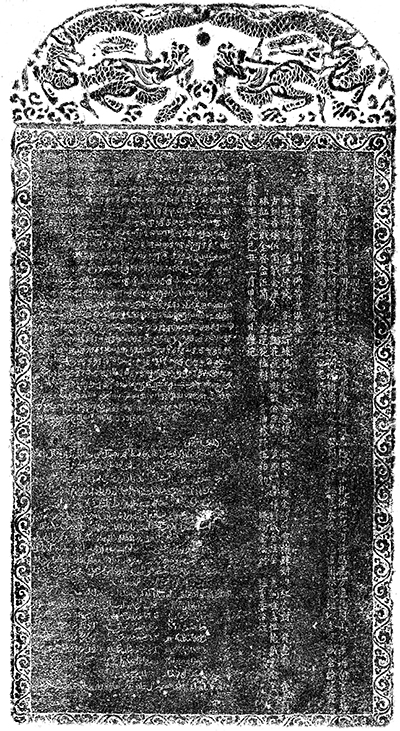

"What we have here is a piece of tangible proof of the legacy of Zheng He — Ming (1368-1644) China's, and arguably Chinese history's, greatest maritime explorer," says Gao Jie, the exhibition's curator, gesturing toward a rubbing of a stone stele on display.

Unearthed in 1911 in Galle, a port city on the southwestern coast of Sri Lanka, the stele records Zheng's offerings and donations at a local shrine during a stop on his second voyage, and features inscriptions in Chinese, Persian and Tamil.

"Far more than feats of navigation, Zheng He's voyages were acts of cultural diplomacy — designed to elevate the Ming Dynasty's stature across the diverse societies of the Indian Ocean world," Gao adds.

Stretching from China to the east coast of Africa — where shards of Chinese porcelain dating back to the 15th century have been unearthed — Zheng's voyages followed meticulously planned routes through Southeast Asia, South Asia and the Middle East.

These expeditions laid the groundwork for centuries of trade and diplomacy, leaving behind a trail of cultural relics scattered along the shores of history.

At its height, Zheng's fleet included nearly 300 ships and a crew of 20,000, among them a large medical corps. A stone epitaph rubbing of one of the doctors who served in the fleet is featured in the exhibition.

"Although the exact dimensions of Zheng's legendary wooden vessels remain debated, there is no doubt that his fleet was designed to awe," says Gao.

"However, the goal was never conquest."

ALSO READ: Tuning in to the past

According to the curator, bu zheng, or not to conquer, was a clearly articulated state policy established by the Hongwu Emperor, the founder of the Ming Dynasty.

"One of the core beliefs," he explains, "was that the Confucian ideals enshrined by Ming society would, in themselves, attract neighboring countries to align culturally and ideologically with China."

Guided by this principle — and wary that open maritime trade might disrupt China's agrarian society and threaten imperial authority — the early Ming rulers tightly controlled overseas commerce. Only the tributary trade system was allowed.

Under this system, foreign missions presented valuable tribute to the Ming court and, in return, received generous imperial gifts, official recognition, and trading rights. The rewards often surpassed the tribute's value, making the system economically appealing.

Carrying overseas highly coveted Chinese goods such as silk and porcelain, Zheng returned not only with spices and precious gemstones — some of which were later crafted into elaborate accessories found in the tombs of Ming vassal kings and their consorts — but also with dozens of diplomatic envoys and royal representatives from places he had stopped by, including Sri Lanka, where the aforementioned stone stele was found.

Believed to be funded in part by wealth from Zheng's voyages, the Da Bao'en Temple in Nanjing was one of the grandest Buddhist temples of the Ming Dynasty.

Covered in glazed brick, it stood as an architectural marvel before its 19th-century destruction. It was frequently depicted in copperplate prints that circulated in Europe, shaping Western visual imagination and perceptions of imperial China.

Yet, the true talk of the town was the arrival of exotic animals — zebras, lions, leopards, ostriches, and most notably, giraffes — first presented to the Ming court by envoys from Bengala, an ancient kingdom located in what is modern-day Bangladesh, which had likely obtained the creatures from elsewhere.

In an article accompanying the exhibition catalog, Wang Guangyao, a researcher from Beijing's Palace Museum, delves into the political symbolism of the giraffe during the early Ming, when it was linked with Qilin, one of Chinese culture's most iconic and revered mythical animals.

"The Qilin was long regarded as a symbol of peace, prosperity and divine favor," writes Wang.

"By declaring its arrival at his court, Yongle Emperor — viewed by some as a usurper for seizing the throne through rebellion against his nephew, the rightful heir of the Hongwu Emperor — sought to affirm his legitimacy and convey to his subjects that he was the one chosen by Heaven."

According to Wang, giraffes were brought to China four times during the reign of the Yongle Emperor, each time as part of the tributary trade.

At the height of the trade, cultural, artistic and scientific exchanges flourished. One example is Korea under the Joseon Dynasty (1392-1897), which maintained a close relationship with Ming China, marked by tributary diplomacy and vibrant cultural exchange.

On display are poems composed by a Ming envoy, followed by responsive works penned by Joseon scholars — writings whose literary merit evidently left a lasting impression on the envoy. Rendered in elegant Chinese calligraphy and presented as a continuous handscroll, the collection stands as a testament to the enduring intellectual affinity between the two cultures, one that persisted well beyond the fall of the Ming in 1644.

The tributary system began to decline after the death of the Yongle Emperor in 1424, as the Ming court scaled back its naval ambitions and imposed stricter haijin ("sea ban") policies, which curtailed the system's economic vitality.

By the mid-Ming period, the rise of maritime powers like Spain, Portugal, and the Dutch — along with the influx of foreign silver — had completely reshaped the landscape of global commerce, drawing Ming China into a global trade network, rendering the sea ban obsolete.

The exhibition includes a blue-and-white porcelain tripod censer from the reign of the Yongle Emperor, its surface wrapped in a dynamic pattern of foaming waves.

READ MORE: The height of bravery

"The motif not only evokes the epic voyages of Zheng He, but also serves as a potent metaphor for the surging currents of change that defined China's engagement with the world during the Ming era," Gao says.