China and Egypt share common features in their ancient roots, Zhao Xu reports.

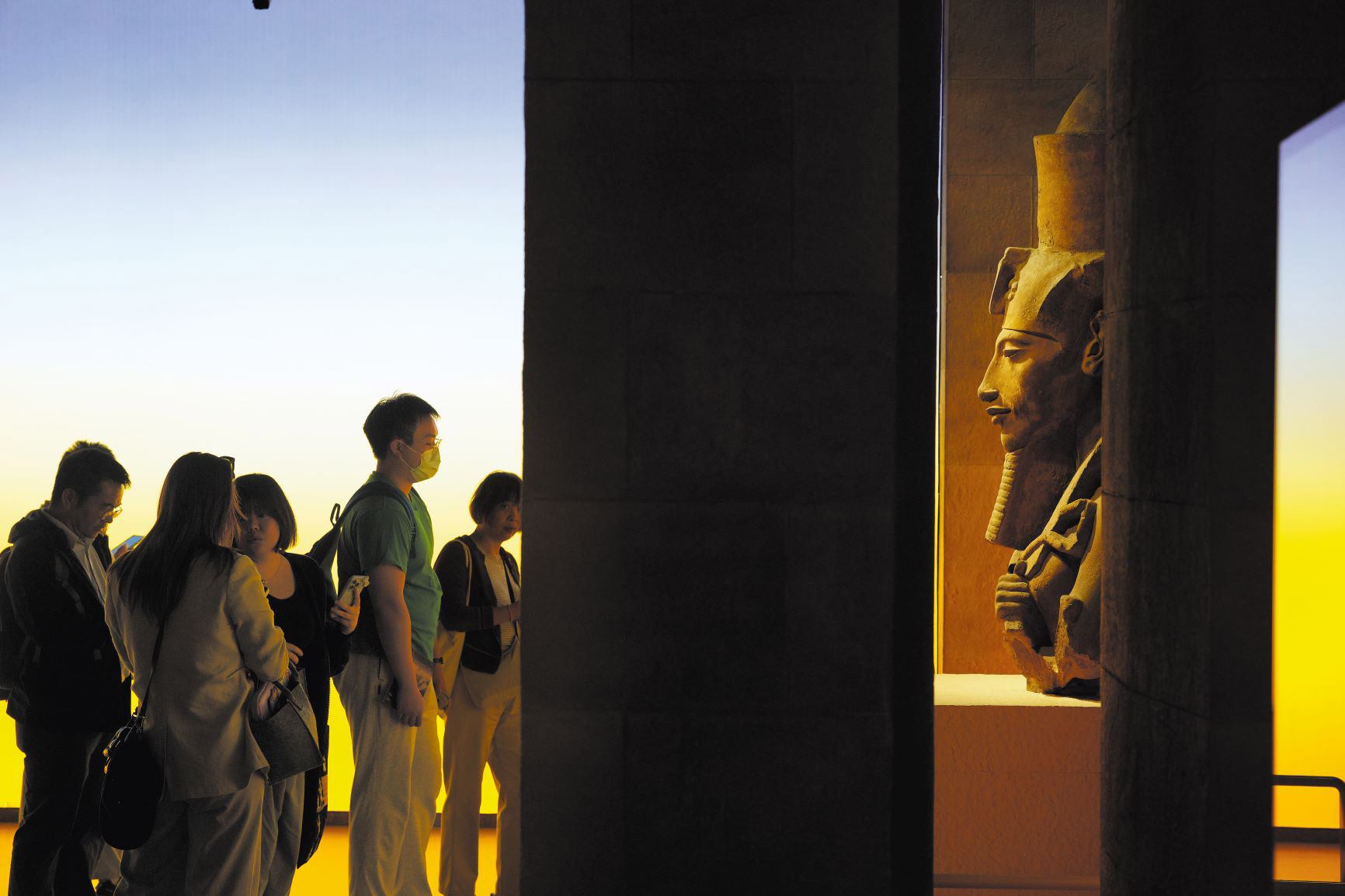

Can you guess which exhibition has drawn the most visitors in the world? On Top of the Pyramid: The Civilization of Ancient Egypt, currently on view at the Shanghai Museum, has welcomed over 2 million visitors since opening in last July, setting a global record for attendance at a single ticketed antiquities show. Of these, nearly 70 percent came from outside Shanghai, with most traveling specifically to see the exhibition.

"It's more than curiosity; it's a longing to understand a civilization as ancient and magnificent as our own," says Xue Jiang, one of the curators. "As two of the world's oldest civilizations, Egypt and China invite comparison, through the sophistication of their art and the shared values they reflect."

That sophistication resonates with Chinese audiences. Just as Egyptian art brims with symbolism, so too does ancient Chinese art — exemplified by the intricately cast bronze vessels of the Shang and Zhou dynasties between the 16th century and 3rd century BC — steeped in ritual and meaning.

READ MORE: Museum visitors eager to experience Egyptology exhibition

"Both civilizations rose along rivers — the Nile, and the Yellow and Yangtze — which shaped their cultures, fostered agriculture, and inspired profound connections to nature," says Xue. "Despite no contact in antiquity, their spiritual and artistic affinities are striking."

The Nile, with its steady, life-giving floods, contrasts with the volatile Yellow River, the harnessing of which demanded resilience and ingenuity. Yet both rivers nurtured worldviews in which nature was not merely endured but revered — shaping ideas and beliefs that echoed the rhythm, cycles, and duality of the natural world.

"Both civilizations embraced the notion of duality: light and dark, order and chaos, heaven and earth," says Xue. In China, this balance is captured in the I Ching, or Book of Changes, a Confucian classic dating to the 11th century BC. Rooted in the interplay of yin and yang, it reflects an early Chinese worldview in which existence was not fixed, but a fluid dance of opposites.

In Egypt, it could be glimpsed in the myth of Apep, the serpent of chaos, who battles Ra, the sun god, each night. Though Apep is vanquished each time, he returns, embodying the eternal struggle to uphold cosmic order.

Fittingly, 2025 in the traditional Chinese calendar is the Year of the Snake. In both cultures, serpents carried profound symbolic weight. On King Tutankhamun's golden mask, the cobra represents Wadjet, protector of Lower Egypt. After Egypt's unification around 3100 BC, Wadjet's cobra joined Nekhbet's vulture on the pharaonic crown, symbols of the unity of the two kingdoms.

Other serpentine deities included Renenutet, goddess of harvest, often shown with a cobra's head, guardian of granaries. The snake, close to the earth, symbolized fertility and the underworld, appearing in royal tombs to guide and protect the soul's journey beyond.

"Both cultures placed deep emphasis on unity, spirituality, and the afterlife," Xue notes. "Egyptians imagined a glorious hereafter, tombs being palaces for the soul, with mummies, amulets, and the Book of the Dead ensuring safe passage through the underworld."

The ancient Chinese shared this longing for permanence. Jade artifacts from the Liangzhu culture (3300-2300 BC), found in tombs along the Yangtze River Delta, were believed to preserve the body for immortality. Later, jade dragons and horses took on a sacred role: to carry the soul to heaven while protecting the body until their reunion.

Some Chinese scholars believe the dragon — Chinese civilization's ultimate totem — may trace its origins to snakes, crocodiles, or both, with crocodiles once common in the Yellow River Basin.

In Egypt, animals were often seen as divine. Hippos symbolized fierce protection; female baboons, maternity; and the scarab beetle — rolling dung across the earth — came to represent rebirth, echoing the sun's daily resurrection.

The elegance and realism of ancient Egyptian art reached its height in the depiction of animals, where art most vividly embraced life. A whip handle carved from ivory takes the form of a galloping horse; a cosmetic box mimics the shape of a wild duck; a stone gargoyle, sculpted as a lion, served as both architectural ornament and protector. Animal and human figures were depicted with each feature shown from its most recognizable angle — heads, legs, and feet in profile; eyes and shoulders frontally — creating a composite image that conveyed an idealized, eternal form. This refined visual language, expressed through dynamic, economical lines, lends ancient Egyptian art a timeless, almost modern, sensibility.

"Though stylistically distinct, the artistic achievements of Chinese and Egyptian civilizations reflect and illuminate each other," says Xue, who also says that both placed great importance on the acquisition of knowledge and the development of writing.

"Both cultures prized learning and employed early pictographic and logographic writing systems."

It is believed that while deciphering Egyptian hieroglyphs, French philologist and orientalist Jean-Francois Champollion (1790-1832) was partly inspired by the principles underlying Chinese character formation, including pictographs and ideograms.

While paper-making is widely, and rightly, credited to China in the early 2nd century, the ancient Egyptians were producing papyrus as early as 3000 BC during the Early Dynastic Period. Ancient Chinese paper-making involved soaking plant fiber like mulberry bark, beating it into pulp, and spreading it thinly on a bamboo screen to dry into paper. In contrast, Egyptian papyrus was made by slicing the papyrus plant's pith into strips, layering them crosswise, and then pressing them to bond and dry, before being polished into smooth writing sheets.

These innovations laid the foundation for historical record-keeping, which flourished in both civilizations. Ancient Egypt and China meticulously documented events, rituals, and daily life through hieroglyphs on stone and papyrus scrolls, or oracle bone inscriptions, reflecting a mutual commitment to the preserving of memory and the continuity of civilization.

Ancient Egyptian society was anchored by the pharaoh and upheld by priests, scribes, and artisans, while peasants and slaves labored below. Yet within this rigid hierarchy, women could rise to power. Among them was Hatshepsut, the first female pharaoh to rule Egypt as a queen in her own right between 1479 and 1458 BC.Her counterpart in ancient China might be Fu Hao, a remarkable queen of the late Shang Dynasty (c.16th century-11th century BC) who lived in the 13th century BC, and served as a general, high priestess, and political leader — an extraordinary fusion of roles rarely held by women in antiquity.

"These trailblazing women offer tantalizing glimpses into two civilizations that have many striking parallels and intriguing contrasts," says Xue, who believes that ongoing collaborations between Chinese and Egyptian archaeologists are deepening cultural ties.

Since 2018, a joint archaeological mission has been underway at the Montu Temple in Luxor's Karnak Complex, in southern Egypt. In 2023, a major initiative led by the Shanghai International Studies University and Egypt's Supreme Council of Antiquities began digitally scanning, photographing, and researching around 1,000 wooden coffins unearthed in Saqqara, south of Cairo, using AI and database technology. Xue, a researcher of Egyptian history and art at the university, is leading the Chinese team on the Saqqara project.

ALSO READ: Chinese tourists experience ancient Egypt coming to life

The two nations are also co-nominating the Baiheliang Inscriptions in China and the Nilometer on Egypt's Roda Island for UNESCO World Heritage status — two ancient hydrological sites that reflect their shared emphasis on water management.

Today, at the United Nations Headquarters in New York, a replica of the ancient Egyptian-Hittite peace treaty, also referred to as the Treaty of Kadesh, is prominently on display. This treaty, concluded around 1259 BC between Pharaoh Ramesses II of Egypt and King Hattusili III of the Hittite Empire, is recognized as the earliest known surviving international peace agreement.

"The replica at the UN serves as a powerful symbol of diplomacy and the enduring human pursuit of peace, which both ancient Egypt and China treasured dearly," Xue says.

"One timeless lesson from ancient Egypt and China is that civilization is not built merely of stone or bronze, but of vision," he continues. "Each sought, in its own way, to understand life and death, power and justice, nature and the divine. They stand as reflections of humanity's earliest dreams. And just as the rivers that once nourished them still flow, so too do the ideas they gave rise to."

Contact the writer at zhaoxu@chinadaily.com.cn