Dedicated rangers in Gansu nature reserve work hard to revive life, ecology

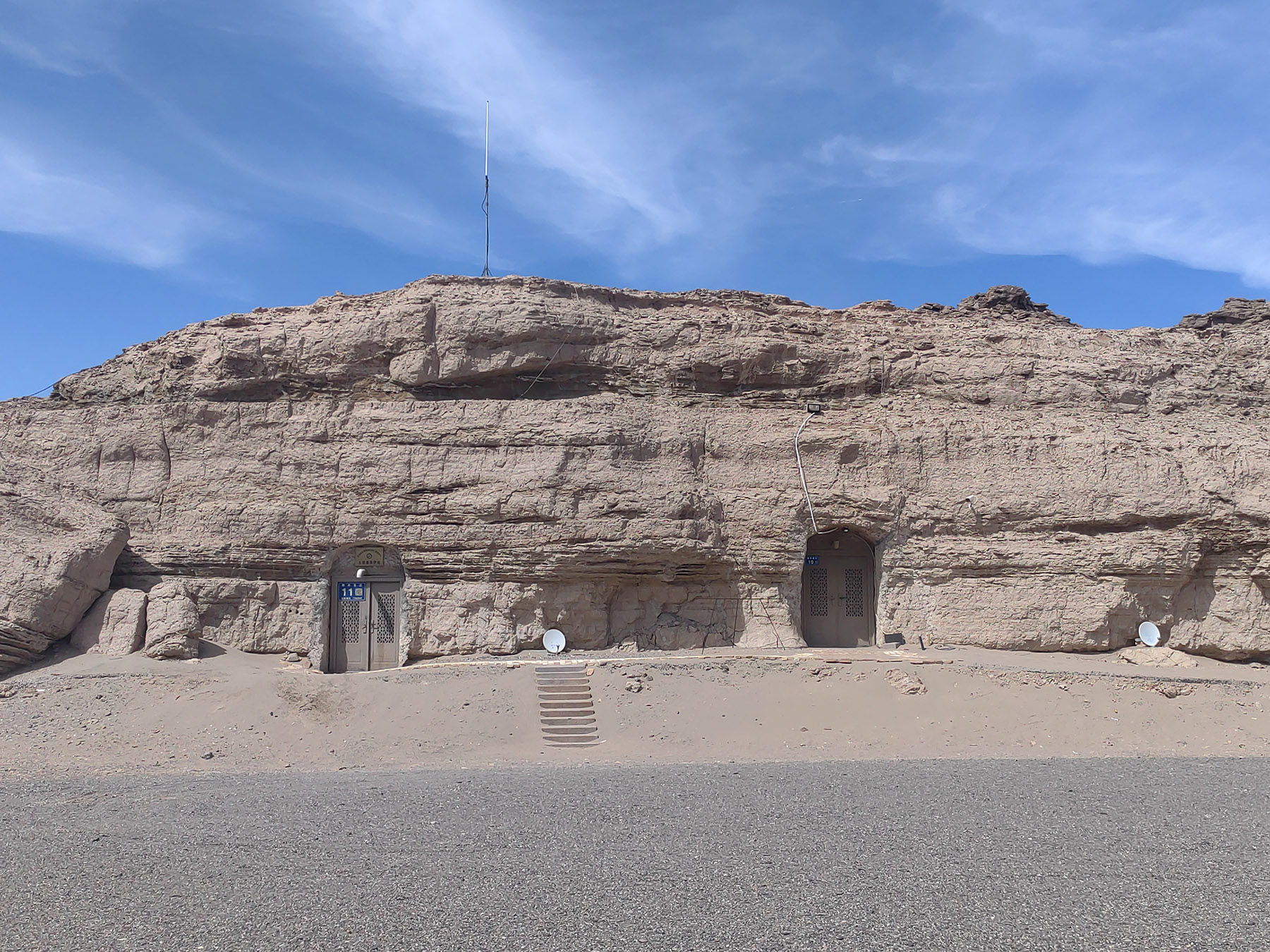

Every year between October and November, the poplar forests in the Dunhuang Xihu Nature Reserve, Gansu province, come alive in a blaze of vibrant, shimmering yellow. Golden shafts of sunlight pour into the cave dwelling of ranger Lu Shengrong, when the door swings open during the day.

Outside, the desert stretches endlessly, its sands tinted a darker shade by mineral-rich gravel — iron and manganese oxides — weathered by wind and sun over the years.

"These are the forces that have shaped both the land and the lives within it, including mine," said Lu.

For the past four years, the cave standing in the reserve's northwestern reaches has served as both his workplace and home. It was carved from a towering, wall-like landform which has been shaped by the relentless sculpting force of the desert wind.

Known as Yardang, or Yadan, these striking formations are a geological hallmark of Dunhuang — an ancient oasis town and important stop along the Silk Road, which once linked China to Central Asia and beyond.

READ MORE: The Great Wall of man and nature

The opening of that great land route in the 2nd century BC sparked waves of migration and land reclamation that ebbed and flowed for two millenniums. Though the desert was always present, the 18th century saw its rapid expansion. Wetlands vanished as migration and overcultivation depleted water resources, allowing the desert's creeping advance.

"What we have done to nature, we must now make right," Lu said, pointing out that Xihu, or West Lake, serves as a reminder of a time when water-rich landscapes stretched across the vast region west of Dunhuang.

"Today, within our 6,600-square-kilometer reserve, approximately 970 sq km are wetlands. This is why the reserve is considered the last natural barrier against the encroaching desert — safeguarding not only the surrounding ecosystem, but also the world-renowned Mogao Grottoes, located about 145 km to the east," he said.

Harsh realities

The reserve was founded in 1993, and Lu became a ranger there in 2011 at age 28.

He said his first task was making the "straw checkerboard". This simple yet remarkably effective Chinese method of sand stabilization involves drying wheat or rice straw and inserting it vertically into the sand to a depth of 15 centimeters, leaving 20 to 25 cm exposed. The grid consists of 1-by-1-meter squares.

The checkerboard traps sand and also captures rainfall. The decaying straw releases nutrients like nitrogen and phosphorus, enriching the soil and fostering plant growth.

Lu recalls waking up early every day to work on the straw checkerboards, continuing until noon when the temperature sometimes soared to 40 C.

"Back then, my workstation — the reserve has four stations in total — was located at the western edge of Er Dun village, a settlement encircled by the desolate Gobi and aptly known as 'the first village of the desert', a name that carries an unmistakable sense of harshness," he said.

Lu said his bungalow was located in the path of the wind." I'd wake up with sand in my mouth — there was simply no way to keep it out, even with the doors and windows tightly shut," he said.

"Every spring, after a winter of howling gales, sand was piled halfway up our bungalow. The trenches we'd dug for planting trees were buried, and it took half a month to clear them. Without that, water — more precious than most things here — would simply run off instead of nourishing the roots."

In 2021, Lu arrived at his current post — Tuliangdao Station — on the northwestern edge of the reserve, which directly faces the forbidding Kumtag, or Kumutage, Desert to its west.

Known for its extreme aridness, massive sand dunes, and proximity to human settlements, Kumtag Desert is a typical shifting-sand desert. Its steady encroachment is believed to have contributed to the disappearance of some major lakes and wetlands that were once part of the West Lake region.

"Nowadays, the entire nature reserve is closed off to human activity," said Lu.

One of the main responsibilities he and his four colleagues share is to monitor anyone attempting to enter the area, whether travelers venturing off the beaten path, poachers, or illegal loggers targeting Euphrates, or desert poplars.

The trees have an extraordinary ability to survive in arid climates as well as exceptional tolerance for saline-alkaline soils found in the region. The reserve contains the largest and most concentrated Euphrates poplar forest in the region.

Lu said a close eye is also being kept on endangered wildlife, most notably wild camels and Przewalski's horses, which are under Class 1 protection.

"Wild camels can be quite aggressive," said Lu, recalling the time he leaped over a tall fence to escape one hot on his heels. "But what truly frightens us are the ticks — they cause unbearable itching, often high fevers, and are nearly impossible to avoid during our field surveys."

He winces at the memory of swarms of ticks crawling over the fur of a dead camel he once had to retrieve for taxidermy.

Between June and September, about 120 wild camels migrate to the Xihu from neighboring reserves in the Xinjiang Uygur autonomous region, said Wu Xingdong, director of another research station.

He said none of the research stations operate in isolation.

"The well-being of our reserve is both affected by and contributes to the health of other nature reserves across the broader region," Wu said.

"We've installed 32 monitoring towers and 14 automatic drinking stations across the reserve to track the 166 horses living here and ensure they have water during the dry season. In winter, we also break the ice so they can drink."

Occasionally, a ranger intervenes to rescue a colt from an adult male that is attempting to eliminate a potential threat.

The horses, named after a Russian explorer and naturalist Nikolai Przhevalsky who brought them global attention, are the last truly wild horse species and historically roamed the steppes of Central Asia.

Several zoos and breeding programs in the West preserved a small population, and reintroduction efforts began in the 1990s in a few natural parks and reserves in Mongolia and northwestern China, among them the Xihu Reserve.

Lonesome ranger

Of the four stations, two, including Wu's, are not connected to the electricity grid, and rely on photovoltaic power generation. Stored energy, however, is not always enough and the stations sometimes experience cold temperatures during periods without sunlight.

Despite such hardships, nothing compares to the profound loneliness of life on the reserve — a desolate place where the whispering of the wind is endless. That companionship of fellow rangers is appreciated and crucial to maintaining mental equilibrium in the harsh environment.

Lu Shengrong, 42, found camaraderie in Tian Shoujun, who is 11 years his senior and began working at Tuliangdao Station in 2017. "I had been a driver before I came here. The truck for our field surveys was no problem until it got stuck in the sand. Then you had to get it out yourself," Tian said with a laugh.

"But there were new things to learn, like filling out field reports and cooking, which I never had to do before when I lived with my family. Here, we take turns cooking."

As he speaks, he confidently stretches strands of hand-pulled noodles, a local specialty. The tiny kitchen where Tian honed his culinary skills — like most indoor spaces at Tuliangdao Station — was carved directly out of the rugged Yardang formations. "We have four cave dwellings. Each one is about 45 sq m and takes around a month and a half to complete," he said.

The landforms, which were once part of the seafloor, are distinctly stratified with layers of hard and soft sedimentary rock.

"The harder layers, like sandstone and limestone, are especially tough to drill through," explained Lu.

"Builders bore at an angle from top to bottom, pour water down the shaft to soften the rock overnight, and resume drilling the next day, sometimes with the help of explosives."

Even a pet dog is given his own Yardang cave — a cool, shaded burrow for escaping the relentless sun.

The caves typically have no windows, as they have no need of wind, and are lit by electric lights from morning to night. Only when the door opens does a sliver of the outside world slip in, with light flooding the dwelling like water through a crack in a stone.

Flowing with life

Less than 100 kilometers to the west of the station lies the infamous Lop Nur, a former salt lake, where biochemist and explorer Peng Jiamu went missing in 1980 — a disappearance that cast the region into the Chinese imagination as a land of mystery, desolation, and drought.

"Not many know that Lop Nur was once part of a salt lake system, fed by the Tarim River from the west and the Shule River from the east," said Lu.

Lop Nur began to rapidly vanish in the mid-20th century, succumbing completely to desertification by the late 1970s. Yet the Tarim and Shule rivers, both lifelines for desert oasis towns and the ancient Silk Road, were not entirely lost. In recent years, significant conservation efforts have markedly improved the situation.

"Dunhuang city, including our nature reserve, lies at the lower reaches of the Shule River. For years, upstream water was so scarce it couldn't even meet farming needs, let alone flow downstream," said Lu. "But that was no longer the case after 2017."

Thanks to renewed water flow, vegetation and wildlife in the area have rebounded. Long-lost bodies of water and reed marshes are reemerging. Migrating waterbirds, now more diverse and numerous, are once again using the wetlands as vital stopovers on their long journeys.

ALSO READ: Finding his station in life

To Lu's greatest relief, the sand dunes now halt wherever grasses take root or wetlands form. "It assures me that what we've endured hasn't been in vain," he said, admitting there were times when nature's reluctance to show signs of recovery had tested his patience.

That patience remains essential. Despite signs of improvement, conditions are still severe in a place where the annual rainfall is less than 20 millimeters.

"The wind is at its most ferocious in April and May," said Lu, who has grown used to sleeping through its unceasing howl. By day, sandstorms churn the earth and sky into a blinding white blur, as if the world has been swallowed by dust.

Contemplating the name "Devil City", a title born from the eerie whistle of wind threading through the jagged Yardang formations, Tian said: "From the reserve's edge, it feels unimaginable. But as you journey deeper, the desert begins to soften. Grassy lakes appear, and golden poplars jolt eyes long dulled by the seemingly unbreakable monotony of sand. It makes you marvel at the fierce yet quiet persistence of life."

Contact the writer at zhaoxu@chinadaily.com.cn