City places high value on time-honored traditions

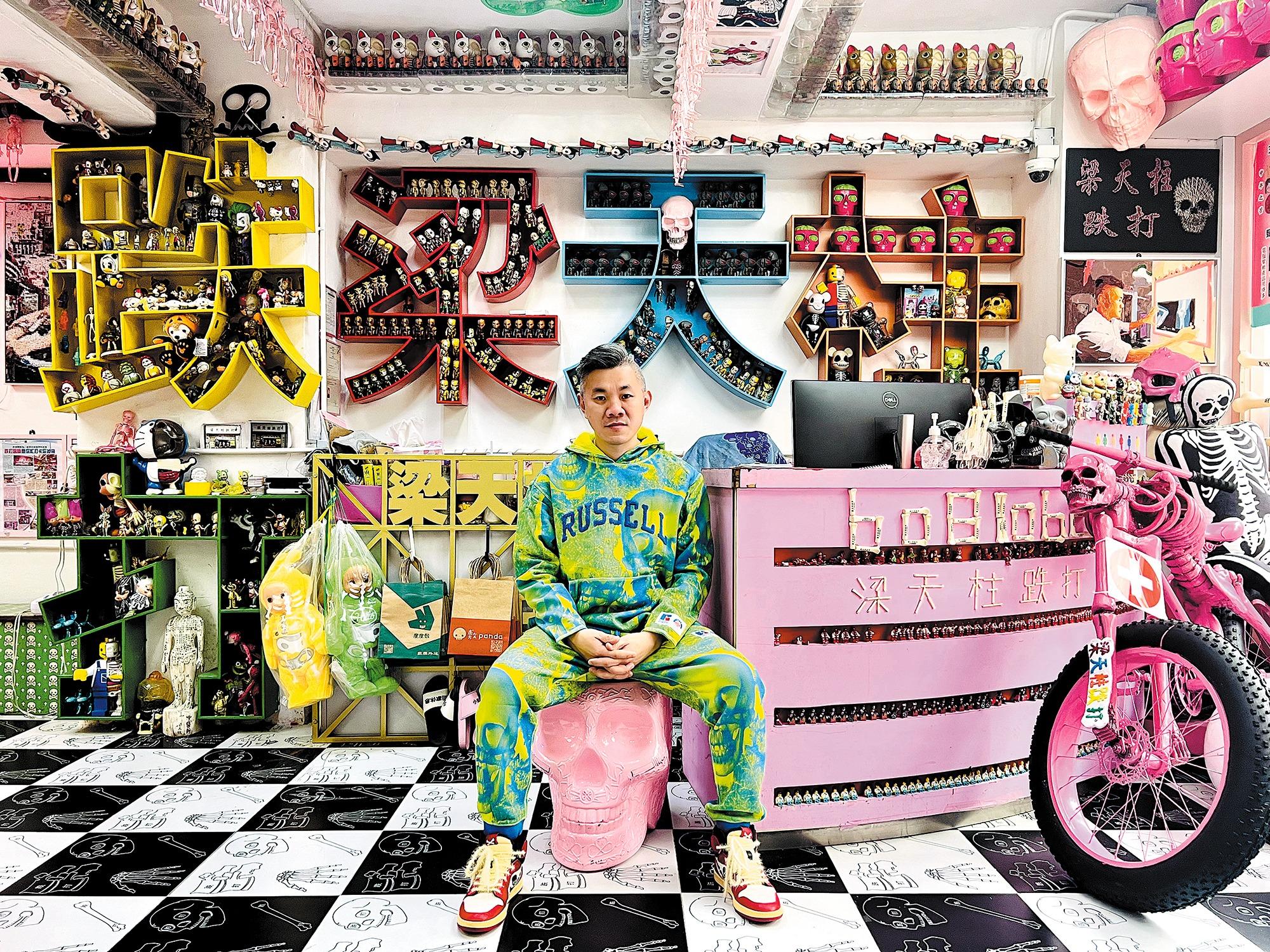

Bone-themed dolls adorn the clinic of Leung Tin-chu, which has been designed as a bone-themed amusement park. (PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Bone-themed dolls adorn the clinic of Leung Tin-chu, which has been designed as a bone-themed amusement park. (PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

To raise awareness of a traditional Chinese orthopedic technique known as dit da, which is designated as an Intangible Cultural Heritage item in Hong Kong, Leung Tin-chu designed his clinic as a bone-themed amusement park.

Located in the Cheung Sha Wan neighborhood of Sham Shui Po, the clinic entrance resembles an arcade, with four dolls and two Japanese vending machines greeting visitors.

The entire space is lit in a pink hue. Rows of pink bones hang from the ceiling, while the walls are adorned with thousands of colorful dolls.

Toys piled high on the floor are printed with bone patterns, while an air hockey game and a game played with a crane claw machine also attract visitors, along with a pinball machine.

Patients head for the bright pink front desk. Several sit on bone-shaped stools, with herbal medicine bags wrapped around their knees. After discovering cartoon graphics such as SpongeBob SquarePants or Hello Kitty printed on the covers of medicine bags, they sometimes use their phones to take photos of the bags.

Others waiting to see Leung explore the premises. Some walk around taking photos of the dolls on the walls, while others play with the claw crane machine.

The clinic is devoid of the sharp smells of disinfectants and medicines. No alarms sound, and there is an absence of stark white walls, which could increase patients' fears. Instead, Leung's clinic is warm and vibrant. As a result, visitors want to stay longer and explore further.

"The whole makeover took me about four years and cost around HK$1 million ($128,000), but it's been worth it," said Leung, a single father in his 40s whose daughter adores the color pink.

Leung said the designs he has used at the clinic help attract patients and spread knowledge about dit da.

Also known as die da, the technique originated in southern China. It adopts methods such as bone-setting, massage, acupressure, and herbal applications to treat musculoskeletal injuries and conditions that include fractures, sprains, bruises, allergies, and swellings.

Dit da was widely used in Chinese martial arts to treat injuries. In the 1960s and 1970s, as martial arts flourished in Hong Kong, the number of dit da practitioners grew. However, with advances in medical technology and the emergence of new treatment methods, awareness of the technique gradually declined.

Leung expects his clinic to raise awareness of dit da, a traditional orthopedic technique. (PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Leung expects his clinic to raise awareness of dit da, a traditional orthopedic technique. (PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Its use in the city is now regulated by the Chinese Medicine Council of Hong Kong, which requires practitioners to hold a professional certificate. In recognition of its cultural significance, dit da was inscribed on the city's first Intangible Cultural Heritage list in 2014.

Leung's decision to enter this field of medicine was influenced by his parents, who ran a dit da clinic, where he helped them care for patients. Seeing the relief his parents brought to patients, Leung decided to become a dit da physician.

After graduating from secondary school, Leung studied on the Chinese mainland. He then returned to Hong Kong to obtain his certificate of practice and work at a Chinese medicine clinic operated by the University of Hong Kong for a decade. When his parents retired, he took over as the second-generation owner of their clinic. With more than 20 years' service, Leung has been awarded over 200 certificates in his field of medicine.

After learning that dit da had become an Intangible Cultural Heritage item, Leung was delighted that the technique had received more recognition, but he was worried about the industry's future.

In the 20th century, Hong Kong boasted thousands of dit da practices, but now fewer than 500 remain, Leung said.

Leung feels that such clinics are unique to Hong Kong. Whereas the mainland is also home to many dit da practitioners, they usually work in larger hospitals, while Hong Kong has distinguished itself with its numerous small, specialized clinics, which feature prominently in local kung-fu films.

Realizing that dit da was often associated with the pungent odor of Chinese medicine, Leung decided to transform his business.

For the past four years, he has worked to improve the clinic by installing new features and decorations each week, most of which he designs himself.

Many of these designs have practical uses, Leung said.

For example, he transformed general medical advice such as "eat more fruit" and "exercise more" into visually appealing wall posters.

Moreover, rather than wearing a traditional white medical coat, Leung frequently opts for jackets adorned with bone shapes and exaggerated cartoon patterns. "I wanted to bring smiles to my patients' faces," he said.

Leung has also launched social media pages to promote his business, gaining more than 300,000 followers. He shares his expertise in livestream broadcasts and on television programs.

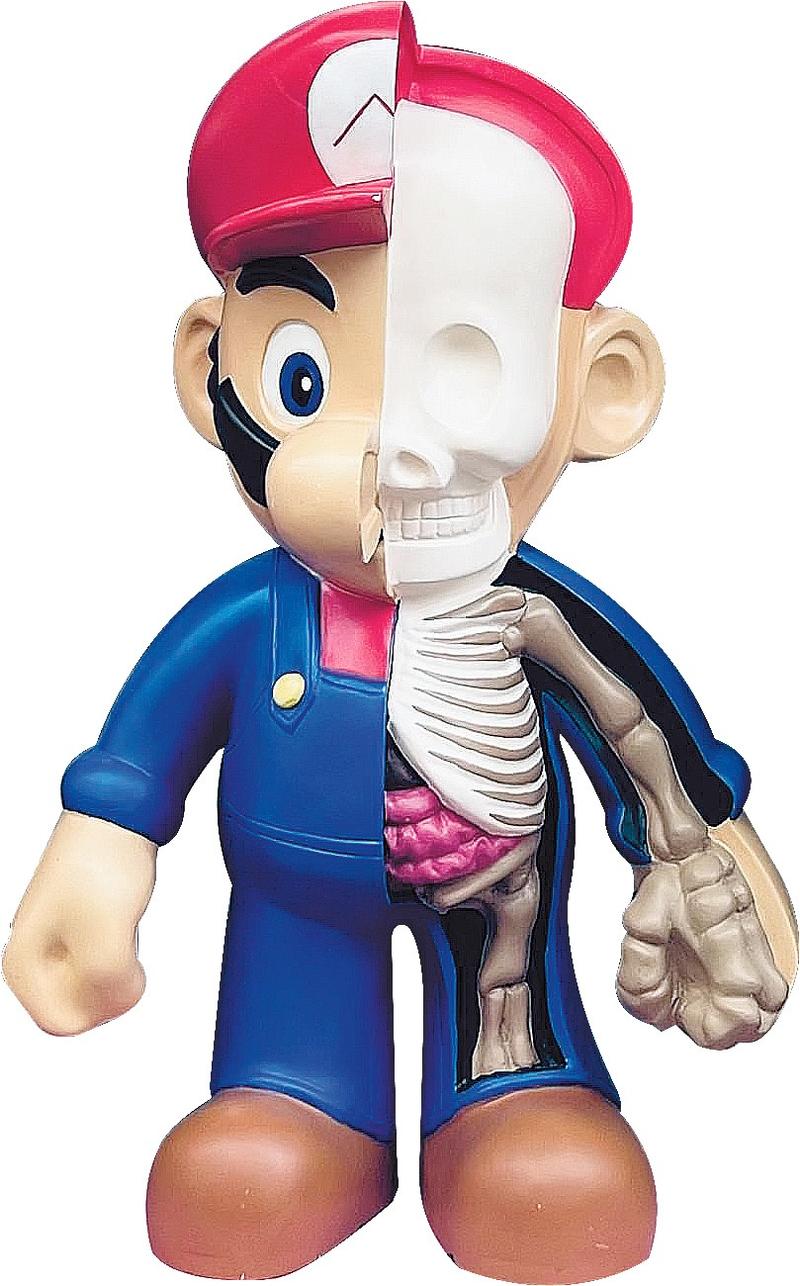

During the COVID-19 pandemic, he arranged for a fleet of vehicles in Hong Kong to distribute care packages. During Halloween, he organized an educational bone workshop for 25 children, teaching them about anatomy, bone structure, and the basics of dit da by using bone toys.

Nima King, born in Iran and raised in Australia, is committed to carrying on Hong Kong's legacy of Wing Chun, a martial art. (PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Nima King, born in Iran and raised in Australia, is committed to carrying on Hong Kong's legacy of Wing Chun, a martial art. (PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

The clinic has attracted wider attention and a group of regular customers, one of them being pole dancer Chan Yu-ki, whose work over the years has resulted in persistent injuries and sudden bruising.

As Western medicine provided little relief, Chan searched online to find new treatments. She discovered Leung's clinic, but having watched gangster films depicting bone-setting shops, she was skeptical about the treatment. However, Leung persuaded her to try it.

Chan soon noticed an improvement. "Western medicine tends to rely on oral administration of drugs, the effects of which take longer to become apparent. However, with dit da, herbal remedies come into direct contact with the injured area, quickly reducing swelling and pain," she said.

Chan returned to Leung whenever she experienced new bruising, and learned that dit da was an Intangible Cultural Heritage item.

"I think Leung's creativity is helpful. Someone like me, who has never paid attention to such heritage, is now more aware of this issue," she said.

Break with tradition

Leung Ka-kit, founder and president of the Hong Kong Intangible Cultural Heritage Association, a local nonprofit organization dedicated to preserving such heritage, said the city boasts hundreds of related items, but preserving them can be challenging when innovation is involved.

Some Intangible Cultural Heritage masters are not willing to adopt new methods, Leung Ka-kit said. For instance, when his organization proposed training craft workers as video bloggers to document the process of creating artwork, some declined, fearing that the secrets of their work would be revealed.

Conservative forces in society also often oppose the introduction of new ideas.

Leung Ka-kit said a Cantonese opera troupe in Hong Kong once integrated the art form into a murder mystery game, with the aim of creating an immersive and interactive experience for audiences. Although there was a positive response, many practitioners of the art form criticized the attempt, claiming it lacked respect for tradition and posed a risk of Cantonese opera being misunderstood.

"Only by first abandoning rigid thinking can new possibilities be unlocked," Leung Ka-kit said.

Louis To Wun, master of a sugar-blowing technique in Hong Kong, said preserving Intangible Cultural Heritage items requires the courage to break with tradition.

The sugar-blowing technique is more than 600 years old. Craft workers use stoves to heat sucrose and maltose into syrup. Before it cools, they knead, twist, press, pull and blow the hot syrup into various figures, such as animals of the zodiac, flowers, birds, insects, and fish. In 2014, the technique was recognized as a Hong Kong Intangible Cultural Heritage item.

Learning the craft by himself, To tested more than 10 kinds of sugar to find the right materials. He injured himself and even caused small explosions when learning to heat the sugar.

But he persisted for more than 10 years until he had fully mastered the technique. Now, To is one of the few sugar-blowing masters in the city who are invited to give workshops and speeches on various occasions.

When passing on this technique to a wider audience, To encountered a common challenge related to handmade Intangible Cultural Heritage items. While numerous people expressed an interest in these craftworks, the high entry threshold required for making them led to many abandoning such attempts.

As a result, To invented a small case that contains a portable sugar-blowing kit. An electric stove displays the temperature required to directly heat sugar to the optimal point, and the case also has separate compartments for storing colored syrups.

To said heritage is best inherited when people actively engage with it in daily life, rather than being separated from it in museums.

Bone-themed dolls adorn the clinic of Leung Tin-chu, which has been designed as a bone-themed amusement park. (PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Bone-themed dolls adorn the clinic of Leung Tin-chu, which has been designed as a bone-themed amusement park. (PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Self-defense lessons

Nima King, an overseas instructor, teaches Wing Chun techniques to his Chinese students at a martial arts school in Hong Kong's Central district, where calligraphy scrolls and Chinese paintings adorn the walls, and incense hangs in the air.

Wing Chun is a style of kung fu that emphasizes close-quarter combat, quick punches and tight defense to overcome opponents.

In the 1950s, several renowned Wing Chun masters moved to Hong Kong, including the legendary Ip Man. They established schools to develop Wing Chun as one of the city's most iconic traditions. Interest in martial arts has waned in recent decades, but in 2014, Wing Chun was designated an Intangible Cultural Heritage item.

King, born in Iran and raised in Australia, is committed to carrying on the city's Wing Chun legacy.

In 2003, when he was 21, he attended a lecture given by Chu Shong-tin, an apprentice of Ip Man, who traveled to Australia from Hong Kong to promote Wing Chun. King was selected to engage in friendly competition with Chu, who was in his 70s. The confident King never expected to be swiftly struck to the floor by the elderly master, an action that left him stunned.

Despite not being able to speak Chinese, King soon decided to learn Wing Chun from Chu. He saved for two years, and in 2005, moved to Hong Kong, where he joined Chu in intensive training courses. He devoted up to six hours a day to Wing Chun and continued the courses for nine years until Chu's death.

In 2008, to pass on Chu's dedication and popularize Wing Chun, King established the Mindful Wing Chun martial arts school in Hong Kong.

Departing from the traditional master-apprentice model, where the master admits only the most talented students, teaching them at home, King set out to introduce a modern and commercialized approach to Wing Chun education.

First, he developed a comprehensive curriculum system that split Wing Chun routines into different levels, each with increasing difficulty, to ensure a progressive learning experience.

King then introduced a skill assessment system, where students demonstrated specific moves at each level. Only after their performance meets certain standards can they progress to the next level.

He also introduced a reward system. Adult students receive certificates when they complete each level, while children are awarded different colored belts.

King's school stood out with its emphasis on the importance of focused attention in every class. During classes, if he notices a student becoming distracted, King quickly redirects the student's focus.

Bone-themed dolls adorn the clinic of Leung Tin-chu, which has been designed as a bone-themed amusement park. (PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Bone-themed dolls adorn the clinic of Leung Tin-chu, which has been designed as a bone-themed amusement park. (PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

As concentrating hard has a meditative effect, those facing high levels of stress, such as senior executives, directors and white-collar workers, refer to King's school as "a temple within a bustling and noisy city".

"Unity of mind and body is a fundamental principle rooted in Wing Chun and Chinese philosophy. I just highlight this aspect in my curriculum to meet contemporary needs. This is also why my school is named Mindful Wing Chun," King said.

The school has flourished, attracting thousands of students to become one of the largest kung fu institutions in Hong Kong. Many of King's students come from countries such as the United States, Germany, Canada and Australia, and when they return home, some of them open their own schools to spread knowledge of Wing Chun.

In 2012, King started to create Wing Chun videos online. He gave detailed explanations of his practice, edited the footage, and uploaded the videos to the internet.

The videos can be bought online, and the initiative has attracted more than 400 students from around the globe. "Now, even if I die tomorrow, the next generation can watch my channel to learn about Wing Chun," King said.

For him, the essence of inheritance lies in keeping up with the times. "If there is a need, I am open to incorporating advances such as the metaverse and virtual reality technology into my teaching," King said.

Leung, from the Hong Kong Intangible Cultural Heritage Association, feels that while protecting cultural heritage is crucial, fostering its growth and evolution is even more important. There are numerous possibilities for innovation and advancement, and breaking away from traditional and rigid thinking is vital for embracing these possibilities, he said.