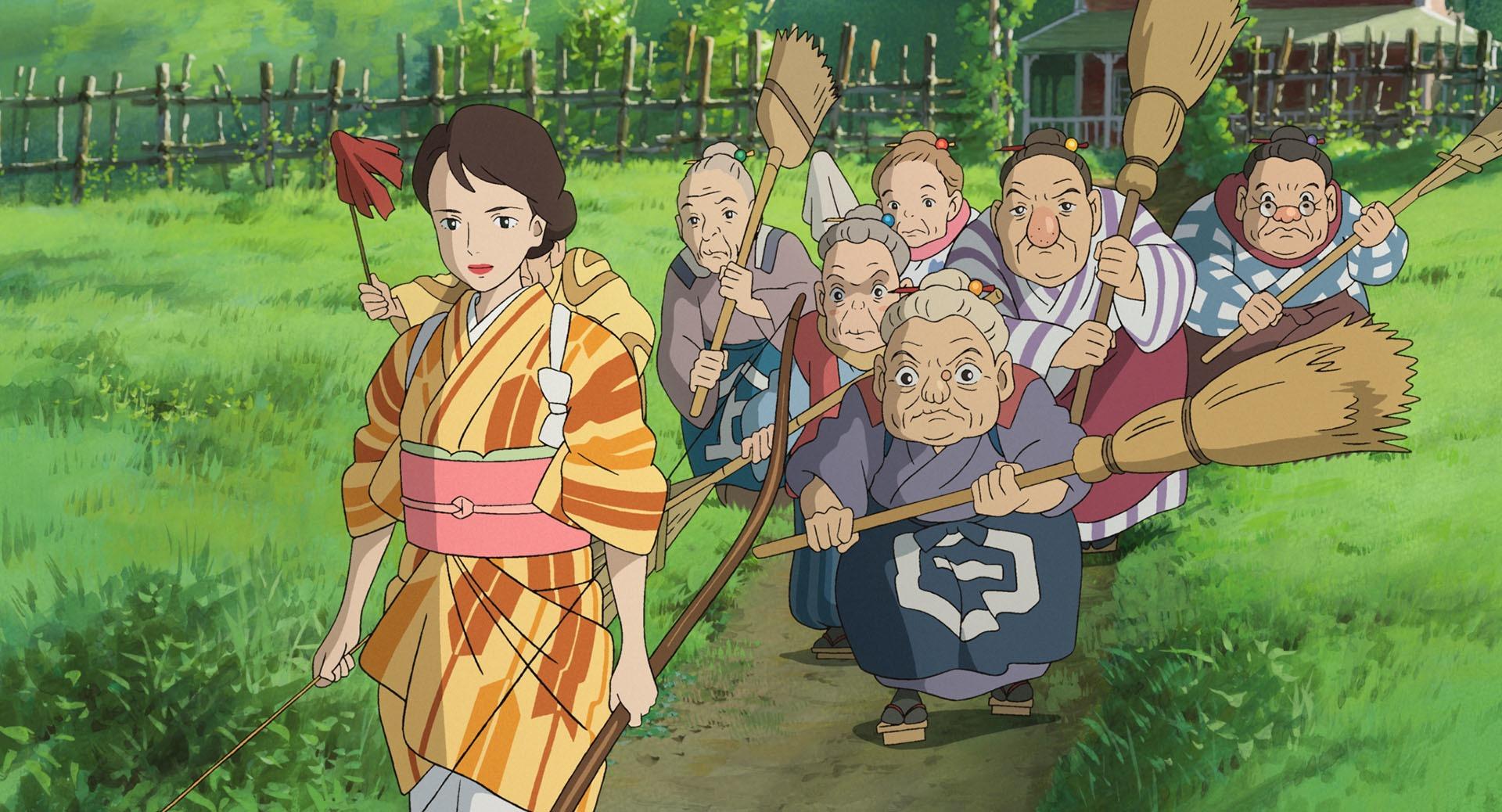

The Boy and the Heron, written and directed by Hayao Miyazaki. Starring Soma Santoki and Masaki Suda. Japan, 124 minutes, IIA. Opened Dec 14. (PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

The Boy and the Heron, written and directed by Hayao Miyazaki. Starring Soma Santoki and Masaki Suda. Japan, 124 minutes, IIA. Opened Dec 14. (PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Japanese animator and director Hayao Miyazaki is such a titan of the form that it’s hard to believe he’s made only 12 films since founding the equally titanic Studio Ghibli in 1985. Miyazaki has been an influence on artists we now consider among the world’s best animators, including Pixar’s Pete Docter (Up), Dean DeBlois (Lilo & Stitch) and Travis Knight (Kubo and the Two Strings) — and that’s not counting the scores of artists in Japan and non-animation filmmakers. Miyazaki’s intensely humanist work casts a long shadow.

But in many ways it’s extremely easy to believe that he’s made only those 12 — a list that has indisputable classics Princess Mononoke and Spirited Away on it. For as a writer he has revisited those humanist themes — of isolation, of our collective relationship to and exploitation of nature, of the loss of social and cultural traditions, and, above all, of non-violence as a response to a violent world. Miyazaki’s World War II childhood has been well documented, and a great many aspects of his own life have made their way into his work. If The Boy and the Heron truly is his very last film, it couldn’t have come at a better time. Beautiful and emotionally rich as it occasionally is, Miyazaki is yet again dipping into a very familiar well, and the story is starting to get old.

The Boy and the Heron, written and directed by Hayao Miyazaki. Starring Soma Santoki and Masaki Suda. Japan, 124 minutes, IIA. Opened Dec 14. (PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

The Boy and the Heron, written and directed by Hayao Miyazaki. Starring Soma Santoki and Masaki Suda. Japan, 124 minutes, IIA. Opened Dec 14. (PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

In 1943, Japan is still in the grips of the Pacific War. The boy of the title is Mahito Maki (voiced by Soma Santoki). After losing his mother to a Tokyo hospital fire, he relocates to the countryside with his father, munitions worker Shoichi (Takuya Kimura) and his new wife, his mother’s younger sister Natsuko (Yoshino Kimura, Masquerade Night). While Mahito tries and fails to fit in with the new community, he’s pestered by an aggressive grey heron (Masaki Suda, Father of the Milky Way Railroad), who lures him into the ruins of a tower on the estate. He thinks nothing of it, but when Natsuko wanders into the ruins, Mahito and the heron follow her and end up in an alternate world, ruled by Natsuko’s granduncle (Shohei Hino). Granduncle’s peaceful stewardship is threatened by the war-happy, man-eating Parakeet King (veteran Jun Kunimura, The Roundup: No Way Out) and his minions.

Anyone even moderately versed in Miyazaki’s oeuvre will see dashes of Spirited Away here, The Wind Rises there, as well as a splash of Kiki’s Delivery Service and a bit of Howl’s Moving Castle. It has the same loosely autobiographical storytelling we’ve seen many times before, and of course the magical characters and adorable creatures of the imagination. The Heron is as charmingly cranky as any of Miyazaki’s dreamworld guides, and the tension between the child’s world as it exists and the way they want it to be forms the backbone of the story. Mahito slowly edges toward reconciling his simmering grief caused by his mother’s death, and finds a way to deal with his father’s warmongering job and out-of-the-blue second wife. All of it is mirrored in Granduncle’s alternate world, which he could have been transported to because he is reading a book his mother left him: Genzaburo Yoshino’s 1937 novel How Do You Live?

The meta nature of the book, about growing up and growing into an ethical person, adds a not-so-subtle layer to the proceedings. It’s just that we’ve seen this all before in one form or another.

What saves The Boy and the Heron from being a slog (though it is rather long) is the unsurprisingly masterful artwork. The parakeet army, the bubbly Warawara spirits, the team of house maids and the opening inferno are all artistic wonders. They’re the reason a Miyazaki film can never truly be bad.