Global Sinologists unite to decipher ancient bamboo manuscripts for fresh insight into early China’s history

The launch ceremony for the first volume of The Tsinghua University Warring States Bamboo Manuscripts: Studies and Translations series is held in Beijing on April 27. (PHOTO / COURTESY OF THE RESEARCH AND CONSERVATION CENTER FOR UNEARTHED TEXTS AT TSINGHUA UNIVERSITY)

The launch ceremony for the first volume of The Tsinghua University Warring States Bamboo Manuscripts: Studies and Translations series is held in Beijing on April 27. (PHOTO / COURTESY OF THE RESEARCH AND CONSERVATION CENTER FOR UNEARTHED TEXTS AT TSINGHUA UNIVERSITY)

Sinologists of various nationalities have been working with their Chinese counterparts on the research and translation of ancient bamboo manuscripts collected by Tsinghua University in Beijing. The first volume of their efforts on the relics from the Warring States Period (475-221 BC), including updated research findings and annotations, was published in late April.

Besides high-quality images of the original manuscripts, which are written in the script of Chu state — comprising what is today’s Hubei and Hunan provinces in Central China and more — the book also transcribes the texts into modern Chinese and translates them into English, and has been subjected to peer review.

Another 17 volumes of the series, The Tsinghua University Warring States Bamboo Manuscripts: Studies and Translations, will be completed in the future, Edward L Shaughnessy, director of the Creel Center for Chinese Paleography at the University of Chicago, said at the book launch event held at Tsinghua on April 27.

The 71-year-old is the main contributor to the first volume, which centers on six texts related to Yi Zhou Shu (Leftover Zhou Documents), a quasi-canonical collection of scriptures from the Zhou Dynasty (c.11th century-256 BC), and Pseudo-Yi Zhou Shu. Pseudepigrapha, in studies of historical literature, are ancient texts whose real authors attributed the texts to a, usually notable, figure or work of the past.

The cover of the first volume in the series. (PHOTO / COURTESY OF THE RESEARCH AND CONSERVATION CENTER FOR UNEARTHED TEXTS AT TSINGHUA UNIVERSITY)

The cover of the first volume in the series. (PHOTO / COURTESY OF THE RESEARCH AND CONSERVATION CENTER FOR UNEARTHED TEXTS AT TSINGHUA UNIVERSITY)

In the introductory chapters and the appendix of the first volume, Shaughnessy provides a comprehensive introduction to Yi Zhou Shu, its textual history, and its relationship to the manuscripts housed at Tsinghua.

According to Shaughnessy, it took the team of 14 — comprising eight nationalities and drawn from various universities and academic institutions around the world — three years to complete the first volume, and more scholars are expected to join them for further volumes.

The book series targets both domestic and overseas scholars specializing in studies of early China and readers who are interested in ancient Chinese civilizations, aiming to help them build a better knowledge of traditional Chinese culture, said Peng Gang, vice-principal of Tsinghua.

In 2008, the university received a collection from alumni donations of more than 2,500 bamboo strips, inscribed mainly with early Confucian classics and historical records.

Their contents include historical chronicles, pre-Qin (before 221 BC) thoughts on governance, warcraft and the rule of law, mathematics and ancient astrology. Notably, Suanbiao, a manuscript of 21 strips, was recognized by Guinness World Records in 2017 as the oldest decimal multiplication table in the world.

At first, scholars believed that, when arranged in the correct order, it could perform multiplication and division of any two whole numbers under 100, and numbers with a fraction of 0.5.

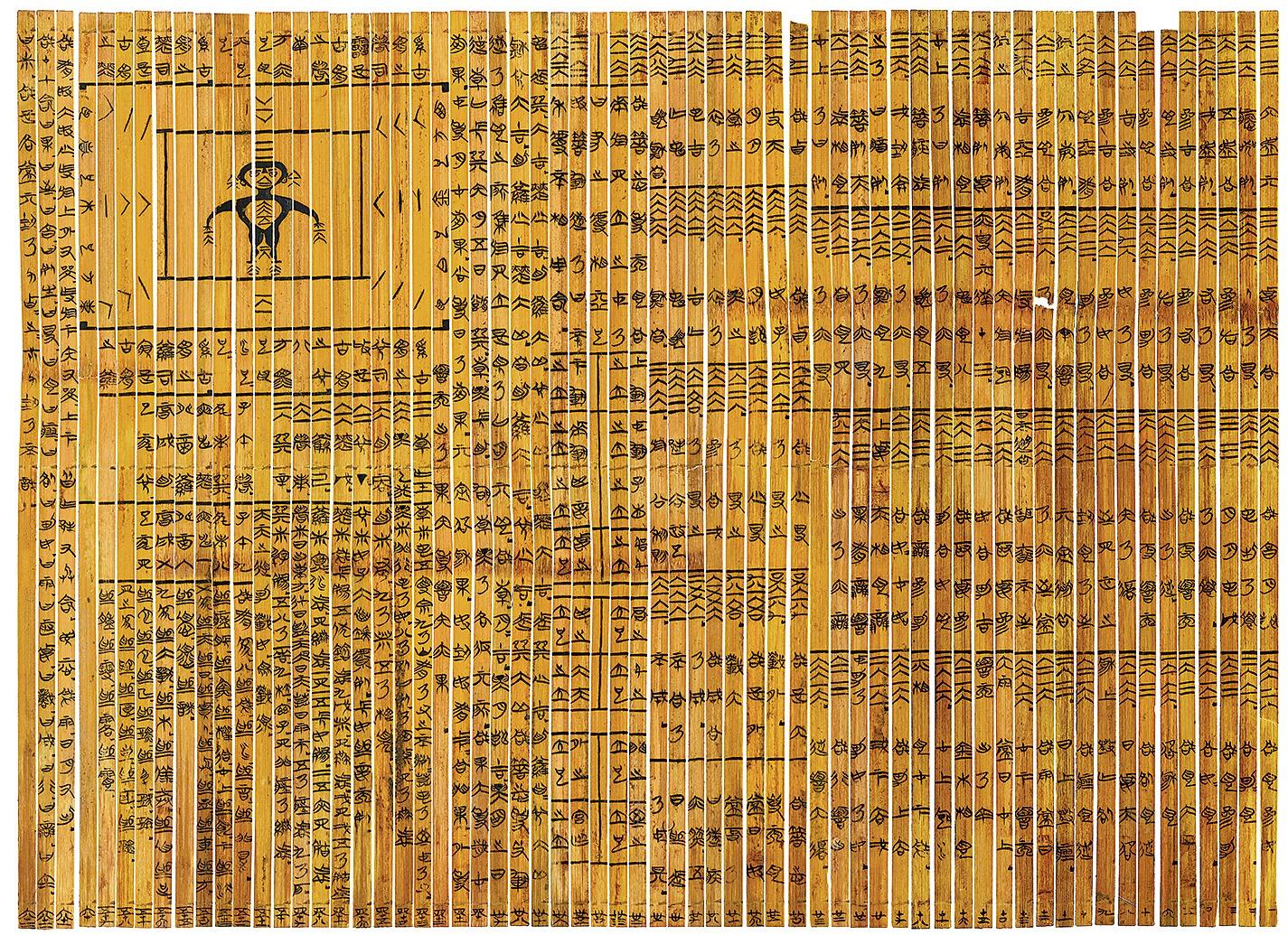

Excerpts of Shifa from the collection, a divination system used in ancient China. (PHOTO / COURTESY OF THE RESEARCH AND CONSERVATION CENTER FOR UNEARTHED TEXTS AT TSINGHUA UNIVERSITY)

Excerpts of Shifa from the collection, a divination system used in ancient China. (PHOTO / COURTESY OF THE RESEARCH AND CONSERVATION CENTER FOR UNEARTHED TEXTS AT TSINGHUA UNIVERSITY)

They later revised that view, speculating that, theoretically, this table can calculate at maximum 495 times 495 — meaning any result of multiplication within 245,025 — and corresponding division, which is much greater than they originally thought.

The collection, comprising around 70 classical texts, contains multiple chapters seen in the Book of History, one of the most important references in the study of early Chinese history. However, parts of the book were lost, and some chapters seen today are proven pseudepigraphical works.

According to late historian and paleographer Li Xueqin, some chapters found in the collection of bamboo strips have discrepancies or different titles to versions transmitted through history; others failed to be handed down for over 2,000 years, but are preserved in the collection.

Li was a key figure in obtaining, preserving and researching the manuscripts. He noted that the original owner, who was buried with them two millennia ago, must have been a historian, too.

Liu Guozhong, deputy director of Tsinghua’s Research and Conservation Center for Unearthed Texts, wrote in a 2021 essay that collecting these classics of the past during his lifetime and using them for burial showed the tomb owner had a wide range of interests.

As the texts were obscure to ordinary people, Liu inferred that the tomb owner was a high-ranking official or nobleman of the Chu state, who had taken on an important position and directly participated in governance of the state.

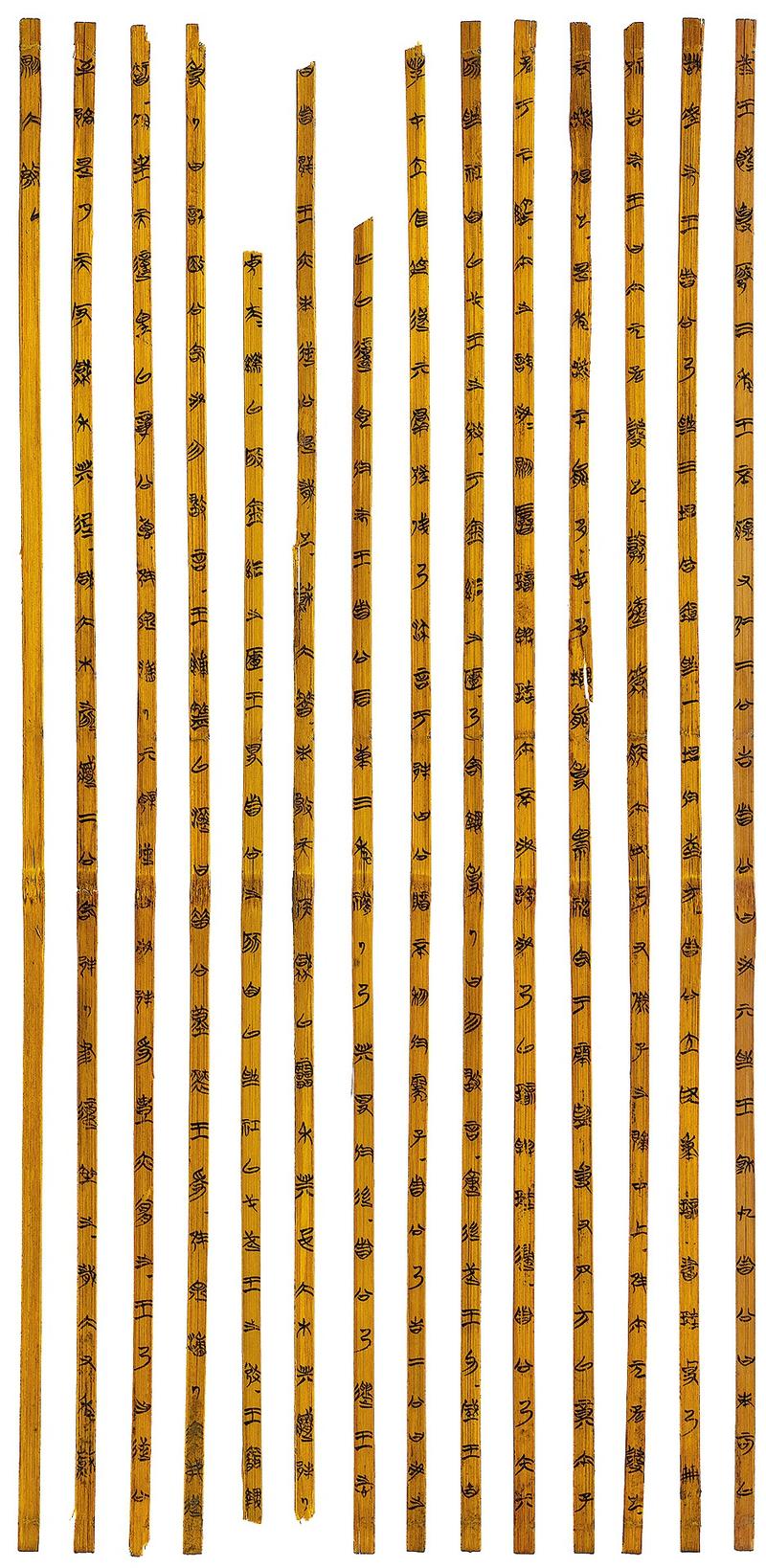

Bamboo strips featuring Jinteng, a text from the Book of History. (PHOTO / COURTESY OF THE RESEARCH AND CONSERVATION CENTER FOR UNEARTHED TEXTS AT TSINGHUA UNIVERSITY)

Bamboo strips featuring Jinteng, a text from the Book of History. (PHOTO / COURTESY OF THE RESEARCH AND CONSERVATION CENTER FOR UNEARTHED TEXTS AT TSINGHUA UNIVERSITY)

Moreover, Liu wrote, the diverse sources of the texts, written in ink on the strips, demonstrate the academic richness and frequent exchanges of thoughts and culture among different states of the time.

At a panel event to discuss the authenticity of the bamboo strips in October 2008, experts concluded that the relics are an “unprecedented major discovery and touch upon the core of traditional Chinese culture. It’s bound to be valued by scholars from home and abroad and will exert a profound influence on subjects like history, archaeology, paleography and philology”.

For over a decade, research into the manuscripts has enriched scholars’ knowledge of ancient written characters, formats and materials used for bamboo strips, as well as the passing down of ancient documents, and advanced the study of the preQin period, exemplified in one text that provides a possible answer to the puzzle of where people of the Qin state originated.

Huang Dekuan, director of the Tsinghua center, where the manuscripts are preserved, says they have collated and restored more than half of the collection, sorting out pieces that belong to the same texts and arranging them to form a complete chapter.

During the process, the scholars have to comb the texts for clues ancient people left when compiling and arranging them, which inspires their study further.

Huang says the center has been publishing an annual volume of Collated Interpretations of the Tsinghua University Warring States Bamboo Manuscripts for 12 years, the ordering of which forms the basis of the arrangement of manuscripts for the research and translation project led by Shaughnessy. Huang added that, hopefully, they will complete the collation and publication of the whole collection in five years.