Communications written on bamboo and wooden strips provide a glimpse into the daily lives of Han Dynasty soldiers, Wang Ru reports.

People visit an exhibition on Juyan hanjian (Han-era wooden or bamboo slips) at Beijing's National Museum of Classic Books in March. (WANG RU / CHINA DAILY)

People visit an exhibition on Juyan hanjian (Han-era wooden or bamboo slips) at Beijing's National Museum of Classic Books in March. (WANG RU / CHINA DAILY)

An envoy was dispatched by the central government to extend regards to officials safeguarding border areas in the Western Han Dynasty (206 BC-AD 24). When he passed Jianshui Jinguan, a military post on the northwest border, local officials received him with rice, mutton and liquor, spending 1,470 qian (a currency unit at that time).Each of the 27 officials shared the expenditure.

Such daily activity taking place more than 2,000 years ago, which normally leaves few traces in the historical record, has been recovered from oblivion, traced through a wooden slip unearthed from the Jianshui Jinguan archaeological site in what is now Jinta county, Jiuquan, Northwest China's Gansu province.

Chinese people’s habit of writing from right to left was inherited from our way of writing on wooden slips, and that was followed until the 20th century.

Xiao Congli, director of the organization and research department of the Gansu Jiandu Museum

This is only a single example of the hanjian (Han-era wooden or bamboo slips recording bureaucratic minutiae, personal letters or contracts) unearthed in the Juyan area, now at the juncture of Jinta and Ejine Banner, Inner Mongolia autonomous region. They record an ocean of information regarding the soldiers who safeguarded the area on behalf of the Han Dynasty (206 BC-AD 220) from 102 BC to AD 169.

Paper was not used widely during the Han Dynasty, so officials mainly wrote on wooden or bamboo slips of different sizes, sometimes linking them with ropes to form a ce, or volume.

Three batches of Juyan hanjian, totaling more than 30,000 administrative documents and personal letters, have been excavated mainly in what is now Jiaqu Houguan site, Jianshui Jinguan site and Diwan site in the Juyan area since 1930.

In 121 BC, Liu Che, or Emperor Wu of the Han Dynasty, set up four prefectures — Wuwei, Zhangye, Jiuquan and Dunhuang — on the far western reaches of the Yellow River, opening the Hexi Corridor, the main artery of the ancient Silk Road, in what is now Gansu.

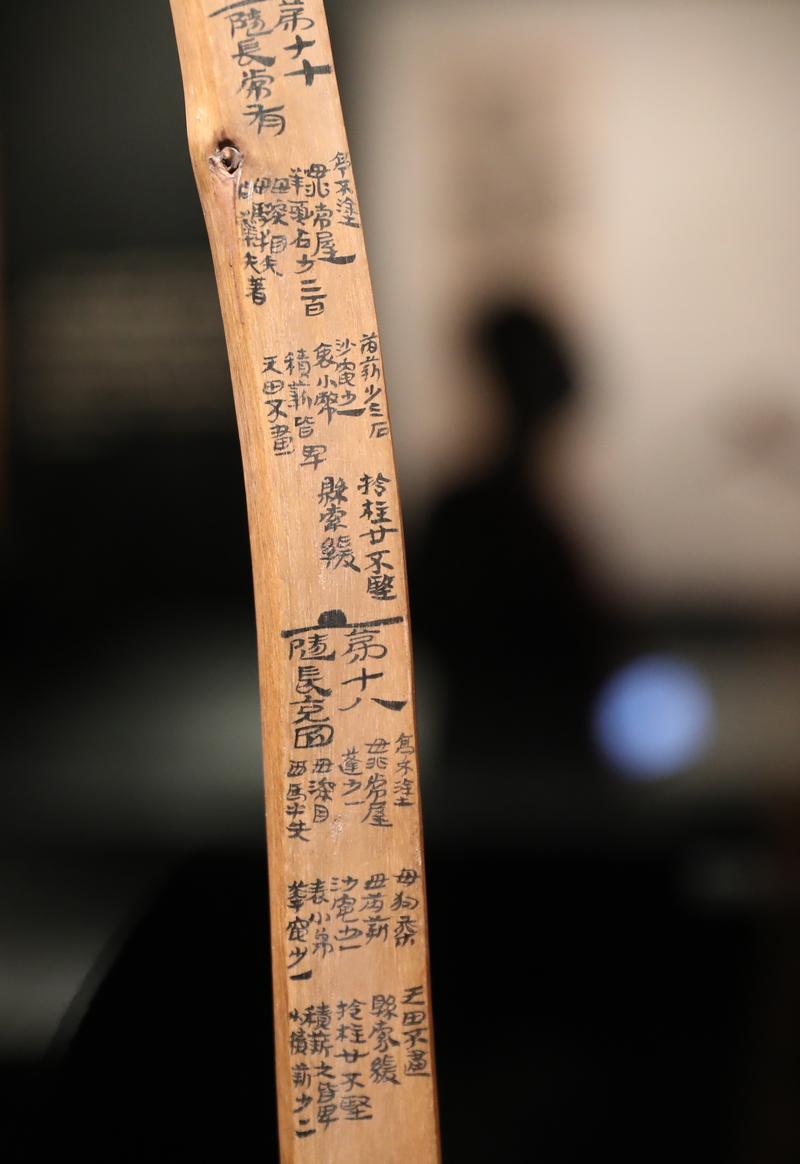

The Juyan wooden slips on display that record bureaucratic minutiae of the Han Dynasty (206 BC-AD 220). (ZOU HONG / CHINA DAILY)

The Juyan wooden slips on display that record bureaucratic minutiae of the Han Dynasty (206 BC-AD 220). (ZOU HONG / CHINA DAILY)

In 102 BC, he established Juyan Duwei Office, a military institute in Zhangye prefecture, to guard against the incursions of nomadic Xiongnu raiders from the north. The soldiers who staffed it were the primary authors of the trove of slips, which record their military and administrative activities and personal stories.

The Juyan slips vividly portray the lives of border defense guards at the time, according to Xiao Congli, director of the organization and research department of the Gansu Jiandu Museum. Jiandu is the Chinese name for bamboo and wooden slips, the main media for writing documents before paper was widely introduced.

"They lived a bittersweet life in Juyan. On the one hand, they had a heavy workload, having to stand sentry, construct military fortresses and do farm work and a lot of chores. The environment in Northwest China was also harsh and many of them got sick not long after arrival.

"On the other hand, the government provided support for them," says Xiao. "They could receive food and clothes, and medical support when needed. They could bring family members with them, and the family members could also receive food, plant crops on farmlands distributed by the government or find other jobs in the local area.

"Some families settled down there, and their offspring later worked as border guards as well."

The Juyan wooden slips on display that record bureaucratic minutiae of the Han Dynasty (206 BC-AD 220). (ZOU HONG / CHINA DAILY)

The Juyan wooden slips on display that record bureaucratic minutiae of the Han Dynasty (206 BC-AD 220). (ZOU HONG / CHINA DAILY)

Stories told

During the Han Dynasty, every male adult had to serve at border areas for one year, and some of them were dispatched to Juyan. Another group of Juyan guards were criminals, who were sent to labor there as punishment.

"There was a system recording each soldier's contribution or misconduct. Conscripts could ascend to a higher position with their contributions, and criminals could reduce their penalties," says Xiao.

For example, a long slip made of a tree branch records the punishment received by Shi Guangde, a local official in Juyan, who failed to fulfill his duties. Shi did not check the watchtowers he was responsible for in time, leading to issues with the military equipment in them. The slip records the specific situation, down to details like the lack of equipment in each tower, and the fact that Shi was flogged 50 times for his mistake.

Besides the administrative records, there are a large number of personal letters, in which people express their feelings about military service, care for friends and family members, and requests for them to provide clothes and other aid.

"Such letters can better show the mental journey of the soldiers, and can help us gain a deeper understanding of their lives at that time," Xiao says.

For Zhu Jianjun, director of the Gansu Jiandu Museum, one of the slips that impressed him the most is a letter from a man to his brother. The letter shows that the man guarding the border area had left his younger brother at home. One day he heard from people coming from his hometown that his brother was sick, and wrote the letter, entrusting the fellow villager to bring it to his brother.

"Judging from where the slip was found, we know the letter was not sent to his brother in the end, but stayed in the garrison for more than 2,000 years," Zhu says. "We don't know if the younger brother recovered later, but after reading the letter we are moved by the emotions in it."

The volume constituted by several wooden slips records a reception at Jianshui Jinguan, a military post on the northwest border more than 2,000 years ago. (PHOTO COURTESY OF GANSU JIANDU MUSEUM)

The volume constituted by several wooden slips records a reception at Jianshui Jinguan, a military post on the northwest border more than 2,000 years ago. (PHOTO COURTESY OF GANSU JIANDU MUSEUM)

Taking stock of the past

Some slips are actually contracts, recording debits and credits. According to Xiao, people often wrote the details two times on a slip, witnessed by a third person. Then they carved a symbol representing the amount of money mentioned in the contract on the slip (at that time there were different symbols denoting numbers), and cut the slip into two halves, dividing the symbol as well. The debtor and creditor each possessed a half respectively. In this way, when conflicts occurred, they could match the two parts to check the complete agreement, and the carving ensured no one could change the amount of money written in the contract.

Juyan is not the only place in Gansu where such slips have been found. The Gansu Jiandu Museum also collects a large number of slips found in other places like Xuanquanzhi, which used to be a postal station in the Han Dynasty.

According to Xiao, the slips have been preserved to this day because of the dry and unchanging climate in Gansu. "They are not easy to preserve for such a long time unless in a stable environment, either very dry or very moist," says Xiao, who also mentions that the Gansu slips are now preserved in vacuum-sealed glass tubes in the museum.

Photos of the Jiaqu Houguan site, where Juyan hanjian slips were unearthed, taken in 1974 (above) and in 2019. (PHOTO COURTESY OF GANSU PROVINCIAL INSTITUTE OF CULTURAL RELICS AND ARCHAEOLOGY AND JUYAN SITE PROTECTION CENTER)

Photos of the Jiaqu Houguan site, where Juyan hanjian slips were unearthed, taken in 1974 (above) and in 2019. (PHOTO COURTESY OF GANSU PROVINCIAL INSTITUTE OF CULTURAL RELICS AND ARCHAEOLOGY AND JUYAN SITE PROTECTION CENTER)

Chinese philologists Wang Guowei and Luo Zhenyu published Liusha Zhuijian (Fallen Slips Buried in the Flowing Sands) in 1914, a book on the wooden slips found by British explorer Marc Aurel Stein in Northwest China. Since then, bamboo and wooden slips have become an increasing object of focus for Chinese and international scholars.

Juyan slips have been regarded as one of the four great discoveries in ancient literature of the early 20th century in China. Study on Juyan slips has been carried out for decades.

"At first, scholars focused on categorizing them, taking photos of them and identifying the words on them. Later, a document management perspective was introduced to study them, which focused on the nature and function of the slips," Xiao says. "In recent years, studies on the calligraphy of the slips, and the evolution of Chinese characters in them have also been popular."

With the improvement of technology, scholars now have access to clearer photos of the slips, and have started projects reorganizing them, he adds.

An exhibition on Juyan slips, organized by the Gansu Jiandu Museum and the National Library of China, opened in Beijing last month, showcasing 155 slips from the sites.

Photos of the Jiaqu Houguan site, where Juyan hanjian slips were unearthed, taken in 1974 and in 2019 (above). (PHOTO COURTESY OF GANSU PROVINCIAL INSTITUTE OF CULTURAL RELICS AND ARCHAEOLOGY AND JUYAN SITE PROTECTION CENTER)

Photos of the Jiaqu Houguan site, where Juyan hanjian slips were unearthed, taken in 1974 and in 2019 (above). (PHOTO COURTESY OF GANSU PROVINCIAL INSTITUTE OF CULTURAL RELICS AND ARCHAEOLOGY AND JUYAN SITE PROTECTION CENTER)

According to Zhu, the slips complement what the canonical texts of the period fail to record, correct mistakes in such books and corroborate what has been recorded in another way.

As important carriers of memory and civilization, slips have traveled through history, borne witness to the emotions and wisdom of the Chinese people, and integrated the spirit and culture of our country, said Zhu at the opening ceremony of the exhibition on Feb 15.

After papermaking was said to be invented by Cai Lun, an official in the Eastern Han Dynasty (25-220), paper gradually took the place of wooden and bamboo slips as the main writing material, but their legacy still exerts a great influence on Chinese literacy today.

"Chinese people's habit of writing from right to left was inherited from our way of writing on wooden slips, and that was followed until the 20th century," Xiao says. "Moreover, many Chinese words we use today to describe books, like juan (a collection of volumes) and ye (page), come from the wooden slip system 2,000 years ago," Xiao says.

Contact the writer at wangru1@chinadaily.com.cn