One of the US' biological laboratories raises serious questions about safety

Personnel at work in the biosafety level-4 laboratory at the US Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases at Fort Detrick in 2002. (OLIVIER DOULIERY / AFP)

Personnel at work in the biosafety level-4 laboratory at the US Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases at Fort Detrick in 2002. (OLIVIER DOULIERY / AFP)

Despite numerous accidents relating to viruses in biological research laboratories in the United States over the years, most seem to gain scant media or public attention.

More than 1,100 laboratory incidents involving bacteria, viruses and toxins that pose significant or bioterrorism risks to people and agriculture were reported to US federal regulators between 2008 and 2012, USA Today reported, citing US government reports it said it had obtained.

An article last August by ProPublica, an independent newsroom that does investigative journalism, said that between January 2015 and June 2020 the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill reported to safety officials at the National Institutes of Health 28 laboratory incidents involving genetically engineered organisms.

"More than 200 incidents of loss or release of bioweapons agents from US laboratories are reported each year," USA Today quoted Richard Ebright, a biosafety expert, as saying. "This works out to more than four per week."

In addition to the bioterrorism laboratory mishaps-details of most of them being cloaked in secrecy ostensibly because of federal bioterrorism laws-questions have been raised since COVID-19 surfaced of the biological research done at Fort Detrick in Maryland.

In July 2019, just months before the US reported its first COVID-19 case, Fort Detrick was temporarily shut by the United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, or CDC, for what were called "national security reasons". By the end of the following March it had reopened.

The closure followed an inspection by the CDC of the laboratories that was said to have found leaks and mechanical problems with a new chemical system it had installed to decontaminate wastewater.

The institute was also working with Ebola and agents known to cause the plague.

Just one month before the shutdown, a mysterious respiratory illness broke out on June 30, 2019, at a community one hour's drive from Fort Detrick.

The Greenspring Retirement Community in Fairfax County, Virginia, had had 63 cases of the disease and three deaths by July 15, 2019, local health authorities said.

Many expressed their concerns over Fort Detrick. Carol Krimm of the Maryland House of Delegates was among those who raised questions about the shutdown and asked for more transparency over any health and safety risks the center posed.

In addition, four doctors from the local advisory committee wrote an open letter to condemn the US army's lack of transparency, CGTN reported. Experts warned irresponsible actions by the army make these high-containment laboratories high risk to local residents.

At the same time, the US was going through one of its worst flu seasons, starting from October 2019 to March 2020, which the CDC said had led to 39 million illnesses and more than 24,000 deaths.

Speculation about the laboratory being the origin of the COVID-19 pandemic have also emerged online.

Robert Redfield, then director of the CDC, admitted in March last year that some COVID-19 deaths in the US had been diagnosed as flu-related. Redfield served as the director of the CDC from March 2018 to January this year.

In March last year a petition in which the signatories sought more information on Fort Detrick was posted on the White House website. US politicians have dismissed the concerns about the center as disinformation and conspiracy theories, and at the same time pushed their own claims about the supposed origins of COVID-19.

In fact Fort Detrick is an army base about 80 kilometers northwest of Washington that was established during World War II and became the hub of the US Army's biological weapons research. Bacteria studied in the laboratories there included the highly infectious and deadly agent anthrax.

During World War II the US government ordered 1 million anthrax bombs from the base, according to NPR.

Military personnel stand guard outside the US Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases at Fort Detrick in 2002. (OLIVIER DOULIERY / AFP)

Military personnel stand guard outside the US Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases at Fort Detrick in 2002. (OLIVIER DOULIERY / AFP)

Notorious ties

Fort Detrick has also had close ties with the notorious Unit 731, a biological warfare organ of the Imperial Japanese Army, which conducted horrific human experiments on prisoners of war and civilians in Northeast China during World War II.

Richard Drayton, a Cambridge University history lecturer, has said the US invited Shiro Ishii, head of Unit 731's human experiments, to be a biological weapons adviser at Fort Detrick.

A New York Times report in 1995 said the US wanted the Japanese research data of biological agents for its own possible military use.

In an article in the journal Critical Asian Studies in 1980 titled "Japan's germ warfare: The US cover-up of a war crime", the US journalist John W. Powell noted the similarities between biological weapons developed by the US and those developed by Japan.

"Infecting feathers with spore diseases was one of Ishii's ideas, and feather bombs later became a standard weapon in America's (biological weapons) arsenal," Powell wrote.

From 1946 to 1949 dozens of interviews and studies relating to Unit 731 were conducted in Fort Detrick, according to a CGTN commentary by Yuan Sha, an assistant research fellow at the Department of American Studies of China Institute of International Studies, citing the US National Archives database.

When the Cold War began, the CIA used Fort Detrick to conduct secret mind-control experiments on humans that often involved unwitting US citizens and prisoners, Yuan said.

Under the cloak of "national security" military scientists freely tested cruel and illegal procedures on human subjects while searching for a so-called truth serum, to make prisoners reveal secrets, Yuan said. The project ended in failure and was shut down by the US government in the 1970s.

In the 1960s the base became a site for high-end research facilities, including the US Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases.

Although the US officially abandoned its biological weapons program in 1969, Fort Detrick has continued defensive research into deadly pathogens on the list of "select agents", including the Ebola virus, anthrax, smallpox and the SARS-associated coronavirus (SARS-CoV).

The laboratory accidents that have happened at Fort Detrick from time to time are part of a long catalog of failures in handling the dangerous pathogens stored there.

Though the closure beginning last year was unusual, it was not unprecedented. In 2009 research at Fort Detrick was suspended when it became known that it was storing pathogens not listed in its database.

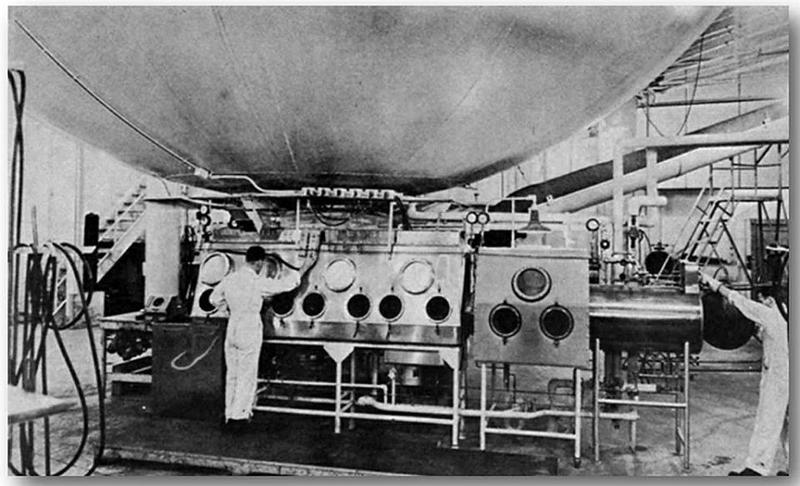

Workers perform tests using the Eight Ball, a 1-million-liter steel sphere built at Fort Detrick in 1952 to measure the virulence of anthrax spores and other airborne bacteria. [PHOTO / AP]

Workers perform tests using the Eight Ball, a 1-million-liter steel sphere built at Fort Detrick in 1952 to measure the virulence of anthrax spores and other airborne bacteria. [PHOTO / AP]

Unsolved cases

In the autumn of 2001 five people died and 17 others became ill during anthrax attacks in the US, after letters laced with the agent were posted to the newsrooms of several media outlets and government figures.

The FBI's chief suspect in the 2001 case, Bruce Edwards Ivins, was a senior biological weapons researcher at Fort Detrick. He killed himself seven years later, shortly before the FBI was planning to charge him over the attacks.

The US has more than 200 biological laboratories in 25 countries and regions. More than 170 of these laboratories continue to operate in the shadows in unknown locations around the world.

According to media reports, some of the laboratories have had large-scale outbreaks of measles and other dangerous infectious diseases, which has drawn widespread concern.

Dmitry Medvedev, deputy chairman of the Russian Security Council, said the US research activities in biological laboratories in countries that belong to the Commonwealth of Independent States have caused grave concern.

The US not only sets up biological laboratories in these countries but also tries to do so in other countries as well, Medvedev said. The laboratories' research lacks transparency and runs counter to the rules of the international community and international organizations, he said.

USA Today reported that since 2003 hundreds of incidents involving accidental contact with deadly pathogens have occurred in US laboratories doing biological research at home and abroad. This may cause the direct contacts to be infected, who can then spread the virus to communities and start an epidemic.