A new exhibition at the Hong Kong Science Museum explores humanity’s 500-year quest to make machines more like us

Maria, Germany, 1927 (2016 replica). Designed for the film Metropolis, Maria’s look evokes the golden mask of the Pharaoh King Tutankhamen. Her striking appearance went on to inspire generations of subsequent robots on film and TV.

Maria, Germany, 1927 (2016 replica). Designed for the film Metropolis, Maria’s look evokes the golden mask of the Pharaoh King Tutankhamen. Her striking appearance went on to inspire generations of subsequent robots on film and TV.

Perhaps we shouldn’t be at all surprised that, since at least the 16th century, humans have been obsessed by the notion of automatons that mimic or mirror the anatomy of our bodies. Standing in front of Articulated Manikin – a miniature figure from late 16th-century Italy that shows the joints of the human body through rivets, screws and intricate iron parts – one isn’t transported into a post-Leonardo da Vinci-inspired future or the realm of science fiction, but into the past by as much as 300 years to the days of knights and medieval warfare, the clanking and the clashing of battleware, and the allure and couture of armour.

Yet the history of robotics goes back much further, with origins in the ancient world. In Greek mythology, Hephaestus created three-legged tables that were mobile, while Jason (of the Argonauts fame) sowed the teeth of a dragon into soldiers. In ancient Egypt, statues of divinities (made of stone and wood or metal) were animated. And in China, the subject of humanoid automatons was outlined in a series of Daoist texts known as Liezi, whereby a royal court is presented with an artificial man by a craftsman. By the 10th century BCE in the Western Zhou Dynasty, the artisan Yan Shi supposedly made a humanoid automaton that could sing and dance. Aristotle speculated in Politics (322 BCE) that automata could establish human equality by realising the abolition of slavery.

From the 16th century onwards, people started to apply mechanical ideas to human bodies, creating concepts such as artificial arms. During the Industrial Revolution, machines began to be used to replace human hands to perform repeated actions, which laid the foundation for robotics. With advances in science and technology, robots that imitate human actions have been developed over the centuries.

In addition to being used in industrial production, robots have played an important role in the realm of science fiction. The term “robot” was coined by Czech playwright Karel Capek in 1920. In Fritz Lang’s 1927 film Metropolis, the female robot Maria, whose look evokes the golden mask of the Pharaoh King Tutankhamun, dances in front of astonished workers. Maria became a blueprint for many of the cinematic and illustrated robots that followed. In 1957, an Italian humanoid robot named Cygan, driven by 13 electric motors and operated by radio control, became quite the talking point. It, too, could dance and perform.

![]() Artificial arms, Europe, 1500–1700. Centuries ago, people started to apply mechanical ideas to human bodies. The wearer of this artificial arm must have looked like a true man-machine.

Artificial arms, Europe, 1500–1700. Centuries ago, people started to apply mechanical ideas to human bodies. The wearer of this artificial arm must have looked like a true man-machine.

In recent years, robots have become more and more human. They can walk on two legs, jump and do somersaults. They can express emotions with facial expressions and look around with eye cameras to capture their surroundings. And just like Kodomoroid, a Japanese newsreader robot and one of the most realistic androids ever created, modern androids can be used to study how people react to robots in order to improve their interaction with humans.

The latest development involves the incorporation of artificial intelligence into robots, thus allowing them to think, react and learn like humans. Witness RoboThespian, an acting robot that “gigs” at science centres, stars in films and plays, delivers stand-up comedy routines and officiates at wedding ceremonies.

Spanning five different periods, the Hong Kong Science Museum’s ongoing exhibition Robots: The 500-Year Quest to Make Machines Human uncovers how automata and society has been shaped by our understanding of the universe, the Industrial Revolution, 20th-century popular culture, and our dreams and visions of the future.

Featuring more than 100 examples, from the earliest automatons to robots from science fiction and modern-day research labs, you can see the latest humanoids in action as you explore how and why engineers are building robots that resemble us and interact in human-like ways. NASA’s Robonaut 2, for example, has been present on the International Space Station since 2011, complementing the work that’s being undertaken by human astronauts.

Given our increasing reliance on technology and our digital way of living, the future is either humanoid or robosapien. From robots evolving into humans, are humans simultaneously devolving or re-evolving, into robots? Only time will tell.

Robots: The 500-Year Quest to Make Machines Human; until April 4, 2021. Hong Kong Science Museum, 2 Science Museum Road, Tsim Sha Tsui East; hk.science.museum

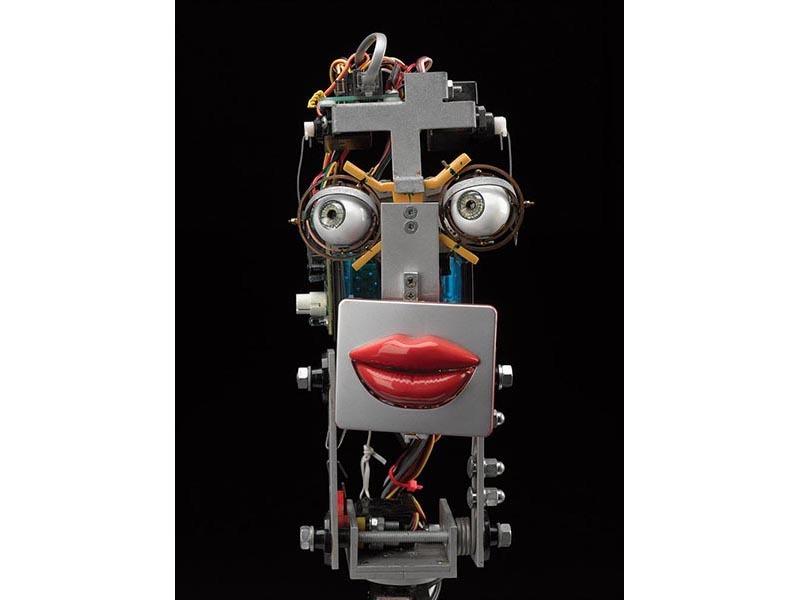

Inkha, UK, 2002. Humans express how they feel through facial expressions and body language. Although Inkha is an expressive robot, it does not feel emotions. However, building modern robots that can express their needs like we do makes them more fun and interactive.

Inkha, UK, 2002. Humans express how they feel through facial expressions and body language. Although Inkha is an expressive robot, it does not feel emotions. However, building modern robots that can express their needs like we do makes them more fun and interactive.

Kodomoroid, Japan, 2014. Designed as a “newsreader” for Miraikan, Japan’s National Museum of Emerging Science and Innovation, Kodomoroid was known as one of the most realistic androids in the world. Besides performance at the museum, Kodomoroid has also been used to study how people react to robots with the aim of ultimately improving how they interact with people.

Kodomoroid, Japan, 2014. Designed as a “newsreader” for Miraikan, Japan’s National Museum of Emerging Science and Innovation, Kodomoroid was known as one of the most realistic androids in the world. Besides performance at the museum, Kodomoroid has also been used to study how people react to robots with the aim of ultimately improving how they interact with people.

RoboThespian, UK, 2016. This acting robot gigs at science centres, stars in films and plays, does stand-up comedy and even officiated at a wedding.

RoboThespian, UK, 2016. This acting robot gigs at science centres, stars in films and plays, does stand-up comedy and even officiated at a wedding.

Images: © WSM Art – Walter Schulze-Mittendorff (Maria); © The Board of Trustees of the Science Museum (Artificial arms, Inkha, RoboThespian); © Plastiques Photography, courtesy of the Science Museum (Kodomoroid)

Click Here for More