Editor’s Note: Shirley Tse represented Hong Kong in Venice Biennale 2019. As a new iteration of her Venice show opens in West Kowloon Cultural District’s M+ Pavilion, in an exclusive interview to China Daily, the Hong Kong-born, Los Angeles-based sculptor and art educator discusses her practice and core artistic philosophy and why these have assumed an extra layer of significance at the time of a raging pandemic.

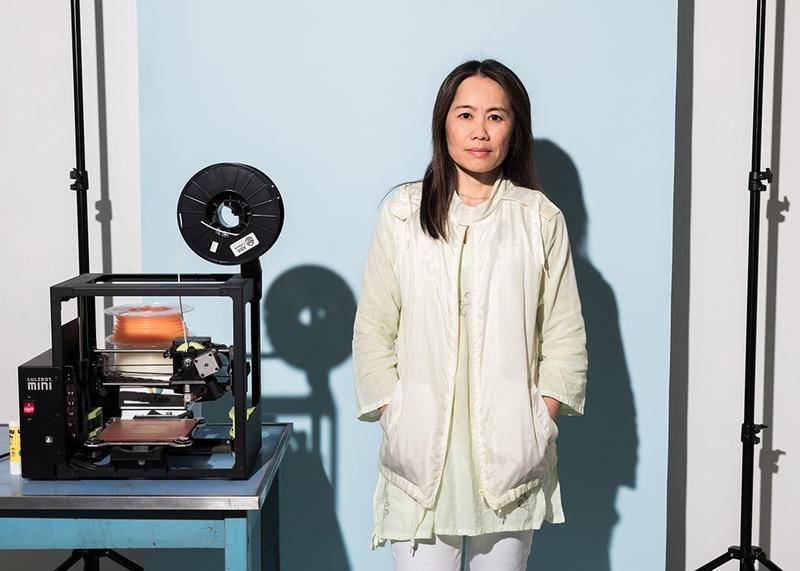

Hong Kong-born artist Shirley Tse is interested in the co-existence of disparate elements and the negotiations involved in trying to situate them in a space. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Hong Kong-born artist Shirley Tse is interested in the co-existence of disparate elements and the negotiations involved in trying to situate them in a space. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Your show was called Stakeholders in Venice but its Hong Kong iteration has been renamed Stakes and Holders. How does this reflect the difference between the two versions?

When we were planning for the Venice exhibition, from the get-go, curator Christina Li and I chose to go with the title Stakeholders for its double meaning – both philosophical and morphological. In management theory, stakeholders refers to the inter-relationships between different constituencies that potentially affect a company or get affected by it. Then if you take the word apart you have stakes and holders. Stakes are wooden or metal sticks with pointed ends driven into the ground to claim ownership of the space demarcated by them. There are a lot of elongated forms in the exhibition, hence stakes. The 3D-printed joints, stands and tripods are the holders – holding other objects.

When we were setting up the Hong Kong exhibition, I wanted the audience to get a clearer understanding of the morphological meaning embedded in the term Stakeholders. So I thought this time maybe take the word apart and call it Stakes and Holders.

Playing on words is typical in my practice. I like to merge concept and objects, idea and materials. So the title, which is both a concept and denotes actual objects, says it all.

Talking of wordplay, does the title hint at something being put at stake?

The idea is that everyone holds a stake in something and at the same time they are all at stake, as they are counting on the (ever-changing) others.

It seems to me you are interested in the theme of contingency. This is reflected in the title of at least one of the two installations in the show: Negotiated Differences.

It is about contingency, as you say. In a world of inter-dependence you are counting on others to maintain equilibrium. I also use the term non-predetermined. Nothing is fixed. A lot depends on how the other components (in this scheme of things) are doing.

After COVID-19, I do not even need to think of a better example to illustrate the idea. One infected person can potentially affect everyone around them.

Change, improvisation and play are at the heart of her practice, says Shirley Tse who represented Hong Kong at Venice Biennale 2019. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Change, improvisation and play are at the heart of her practice, says Shirley Tse who represented Hong Kong at Venice Biennale 2019. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

In the Hong Kong edition of the show, the outdoor-indoor divide of the site in Venice has been done away with and the two installation pieces placed under the same roof, more or less — not counting the antennae in the foyer outside. What difference would you say this has made to the original iteration of the show in Venice?

From the beginning, the two installations, Negotiated Differences and Playcourt, were conceived to be site-responsive installations. So there was never any fixed, original form for these two pieces. Things are changed around during each installation process. Change, improvisation and play are the key things in both installations. I am interested in the idea of differences. The changes (in each iteration) are meant to show these differences.

Since Stakes and Holders is the last show in M+ Pavilion before exhibitions move to the M+ museum (expected to open in 2021), I wanted to draw attention to the architecture of the venue. I thought I would put both installations in the same space, without a partition. Playcourt being an installation that conjures up the idea of games, I wanted to have certain elements from it in the foyer.

I wanted to have two (characteristically) very different installations in the same space, to highlight the ideas of variation, plurality and difference – that one artist’s practice could entail very different kinds of work. In Venice, Playcourt was developed as a response to the site. The open-air space was surrounded by residential buildings. I was actually quite charmed by the lived-in environment with its laundry lines and one could hear people talking on their phones. A lot of the sculptures in Playcourt were installed to point upwards, to the apartments. Negotiated Differences, on the other hand, was about horizontality. I wanted the piece to stay close to the ground. This was reversed in the Hong Kong edition, and the form made more vertical, because in M+ Pavilion we have these really interesting and intricate (network of) exposed air-condition ducts (under the ceiling). I wanted the piece to engage in a dance with the architectural infrastructure of M+ Pavilion.

In Venice, Playcourt is set up like an imaginary outdoor game of badminton played by two people. In Hong Kong it is more ambiguous, one doesn’t quite know if the game is over or about to begin.

For me the extensive use of 3D-printed pipe elbows in Negotiated Differences come across as especially poignant. It exemplifies a way of joining without screwing or soldering together the hundreds of mainly wooden components used in the piece. Is this show meant to pay homage to a humble plumber’s artefact and by extension the community of laborers? Also, could this be a nod to maker culture?

Plumbers’ sockets have a maximum of two openings on one side, whereas the ones I have designed can have seven or even more. I personally 3D-print them, using files downloaded from open-source (platforms) and then have them customized. These are like found objects that exist in the cyberspace, waiting to be downloaded (and given a form). I see them as 21st-century readymade objects. And yes, in a way this does tie in with the maker movement.

If Negotiated Differences is interpreted as bringing different people together, I would say the community of laborers constitutes a very big chunk of it. I come from a family of wage laborers. It is the kind of experience that I can most relate to. I am not sure I consciously pay homage to workmen’s materials, but I like your reading of it.

Stakes and Holders, a new iteration of Shirley Tse's Venice show, Stakeholders, is now on at M+ Pavilion in West Kowloon Cultural District. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Stakes and Holders, a new iteration of Shirley Tse's Venice show, Stakeholders, is now on at M+ Pavilion in West Kowloon Cultural District. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

I liked the humor in Stakes and Holders – the way styrofoam is passed off as jade and mounted on a stand to take on the appearance of a robotic face sticking its tongue out, for example. How important a role does humor play in your works?

Humor is very important in my work. It is related to my interest in paradox and irony. Because I am interested in differences and multiplicity, often times when you bring two things together, if you can use the contrast between them in a surprising way, it can create irony and humor at the same time.

For example, in Jade Tongue (part of the Playcourt installation) I combine polystyrene and nephrite… the first is a polymer, a mass-produced object. And the piece of nephrite has traces of it being manipulated by machine. It is a combination of natural and synthetic materials.

In one of your previous works, in which you used packaging materials, you drew attention to the hollows to underscore the materiality of the object…

From the very beginning, I have been interested in the in-between spaces, also the binaries of positive-negative…

From my research in plastic I realized plastic was invented to mimic natural material, like ivory, and also natural rubber. But soon afterwards, objects made using polymer were about newer forms that did not have a natural counterpart. For example, for one of my older works, Does Cinderblock Dream of Being Styrofoam? I bought pink styrofoam bricks that seem to mimic cinderblocks from a lifestyle store in Tokyo. College students often use cinderblocks as makeshift bookshelves, and these styrofoam bricks are marketed to be a lighter and more fashionable substitute for the same purpose. I see humor in that product. It’s really odd (making styrofoam mimic concrete). Then concrete is no more natural than styrofoam – it’s a mixture of stone, gravel and binder. It’s interesting to think about how we define artificial as opposed to natural and how that line is getting more and more blurred as society moves more and more toward synthetic materials.

Sometimes it appears that the touch of humor in your work is a bit too understated. For example, smaller sculptures such as the flutes in Negotiated Differences might be easy to miss…

Negotiated Differences consists of 393 wooden spindles and 479 3D-printed connectors, so 872 pieces in total. There are hundreds of different types of components, so unless you spend an hour, looking at the installation, chances are you will miss some of them. I hope it is an experience beyond locating recognizable objects. It’s a conceptual piece even though there is a lot of making involved, materials to look at and forms to appreciate. It is not meant to be a mere representational sculpture. Then that is part of my practice: to merge concept and material, ideas and objects together. The idea is to bring all these differences together, and then they have to work with and against gravity in order to (hold together), through a process of negotiation.

We used over 40 species of wood in Negotiated Differences. The pieces were of different length, thickness, color and texture…

It seems you also used branches of trees in their organic forms, just as you found them…

I picked some of them from my backyard. I wanted to include some of these found green wood in my show because these will change over time.

In Negotiated Differences I wanted to mix representational and abstract forms. Under the recognisable objects category, there is furniture – table legs and chair legs. There are architectural elements in the form of balusters, domestic objects like sculptures in shapes of bottles and jars, outdoor sports equipment like baseball bats, hockey sticks and badminton racquets, recreational items like a spinning top and chess pieces, musical instruments, and decorative objects like candlestick-holders. All of these components were made using a lathe machine – the way (wooden artefacts) would be made over a thousand years ago. I visited Morocco to observe the ancient technique of wood turning practised there. There were also pieces of Chinese furniture that were hand-chiselled. We also made objects that referenced the installation itself, like replicas of the long wooden handle of a chisel used to sculpt the wood figures in the sculpture.

One of the spindles is modelled after a graph of me saying, “Stakeholders,” and another one mimics the form of Constantin Brancusi’s Endless Column.

Would you say each of these individually-carved and unique pieces is vitally important to the Negotiated Differences installation as a whole?

Someone told me the idea of assembling different components, dismantling and reassembling sounds like Lego. It’s kind of like Lego, because it’s modular, but unlike Lego, here each piece is unique, with many different possibilities. The only thing that is consistent is the dimension of the holes. I think the idea is to be able to visualize a kind of connectivity between different unique units. They don’t need to turn themselves into interchangeable parts, or be all one size to hold together. It is a whole made of many parts but each part maintains a certain agency. It’s a kind of collectivity that’s not about uniformity.

The Venice edition of Shirley Tse's installation Negotiated Differences, made up of 393 wooden spindles and 479 3D-printed connectors. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

The Venice edition of Shirley Tse's installation Negotiated Differences, made up of 393 wooden spindles and 479 3D-printed connectors. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Negotiated Differences has been compared to a rhizome-like structure that appears to mime the rhythms and patterns seen in nature. Is that about right?

I think rhizome is a good analogy of how I see the connections in this installation. The French philosopher Gilles Deleuze’s concept of rhizome describes connections or a system that is lateral. So it’s non-hierarchical. To me having agency comes with the awareness of others having agency as well. Instead of having a top-down, centralized environment, I prefer to have a method that encourages lateral connection through negotiations.

Would it be fair to call Stakes and Holders a retrospective show of your works, since sculptures from your previous exhibitions figure in it?

In Playcourt, there are three sculptures from a previous show, Lift Me Up So That I Can See You Better. The sculptural language I use has evolved to an extent, over the last 20 years and here they are together in a show. This is like bringing differences together at another level. This show also brings together all the material I have used and all the sculptural methods I have explored – carving, wood work, assemblage, mold-making, 3D printing – to show that contemporary sculptural practice can be very diverse.

When I use the word “negotiation” for this show, it operates at many different levels. It’s about a negotiation between me the artist and the material that is manipulated. And then we negotiate the installation piece’s movement in relation to the ceiling and around the air-condition ducts. So in Negotiated Differences there are negotiations between people, between people and objects, people and object in relation to a space, between two spaces (Venice and Hong Kong), and space and time as well. This is especially true as Christina and I were not able to travel to Hong Kong (because of the COVID-19-related travel restrictions), so we worked with the M+ team via online communication to install the exhibition remotely.

For a long time, plastic was your main sculpting material. What drew you to it?

I was born and raised in Hong Kong. I was surrounded by a lot of plastic during my growing-up years. People seem a lot more conscious of the impact of plastic now than they were in the Seventies and Eighties. At that time we saw more plastic than plants. I remember watching the Kwai Chung terminal in full operation in the early hours of the morning… giant containers being moved by a fully automated system… and being curious about what’s inside.

Later when I was in grad school in Art Center College of Design, Pasadena, California and was looking for material to work with, the sight of styrofoam packaging in dumpsters made me think that the containers I saw in my hometown were full of such styrofoam. It was such a prime signifier of globalization – (a metaphor of) the movement of people and goods all around the world. It also ties in with the theme of migration. Being an immigrant in America, I feel I am always in between, like a piece of styrofoam.

From my research in styrofoam and polymer, I find) the material is temporal in terms of its use but the substance (constituting it) is permanent – it lasts forever. styrofoam is so alien looking, having no similarities with the human figure, and yet it is so ubiquitous that it is second nature to us. In traditional forms of sculpture, you start with an armature and then put the material on it, but with styrofoam you don’t need that. You can use injection-mold technology to build a structure and a surface at the same time. I realized plastic was full of paradoxes, temporal yet permanent, alien yet intimate, surface and structure at once.

In the Fifties, plastic was seen as a chemical product with a thousand uses. Its form symbolized a Utopian, modernist future. By the Seventies, it had become the culprit causing environmental disaster. Plastic is open to different interpretations, yet adheres to none. It inspired my interest in the theme of heterogeneity.

The French philosopher Roland Barthes wrote an essay called Plastic He wrote: “the quick-change artistry of plastic is absolute: it can become buckets as well as jewels.”

But then plastic is only a substance that cannot be good or evil by itself, its culpability depends on how people choose to use it. I think it’s the single use of plastic materials that is really the culprit. It has to do with our culture of convenience rather than the substance itself.

For the longest time, my practice was only about using synthetic polymer. And then one day it dawned on me that plastic was not a substance, in fact it was a formula, a code that chemists use to arrange the carbon molecules in a certain configuration. My focus shifted to plasticity and the syntax – the structure – leading to the state of plasticity.

Playcourt was installed in a courtyard in Venice, with the sculptures pointing upwards at the surrounding apartments. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Playcourt was installed in a courtyard in Venice, with the sculptures pointing upwards at the surrounding apartments. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Indeed, Negotiated Differences does resemble an atomic structure diagram, in a way… Moving on, nomenclature seems to be an important aspect of your work. The wordplay in names like Playcourt, Quantum Shirley, Does Cinderblock Dream of Being Styrofoam, which sounds like a homage to Philip K. Dick, Jack of Heart, Vital Organs seem to add an extra layer of poignancy and meaning, bringing to mind a whole range of, often literary, allusions. Are words your material as well?

I use photography, sculpture and text (in my works). I have used drawings based on words. I do see text as a kind of material. I see language as a body – a concrete form that one can play around with.

After moving to the US, I had seriously considered going for a PhD program in philosophy. Then I thought if I studied philosophy, my main medium would be using words and language, whereas the way I understood the question of the relationships between subject and object, and time and space, was through my body. It seemed if I used only languages and words to experience the world around me I would be missing out. So I decided to go for an MFA in sculpture instead. I thought I would use sculpture to think about philosophical ideas.

Putting your art out in the public domain, outside of conventional gallery spaces, has been quite central to your practice right from the early stage of your career. How does this tie in with the two venues of your most-recent exhibitions in Venice and Hong Kong?

The venue being a public domain is a key theme of the Stakeholders show in Venice. I chose the game of badminton for Playcourt because I really liked playing the game on the streets of Hong Kong, which is an act of claiming a part of the public domain.

Ham radio (part of the Playcourt installation) is similar. It’s basically like a chat room from pre-internet times. That’s how people from round the world made connections in an analogue way, by using radio frequency in the airwaves. Nowadays a lot of these frequencies are being used by governments and corporations, so a very narrow band of frequencies is available for amateur radio operators to use. So those antennae in Playcourt are about staking a claim in that narrow space.

Besides being an artist you are also an art educator. Is there a thought you would like to share with fellow artists and art students, in the light of the pandemic the world is going through?

I take my role as an art educator very seriously. I learn from my students. We are all learning together. In order to do that, we need to have openness. I teach my students so that they can teach themselves, be autodidacts. I am interested in giving them the tools to develop a syncretic approach when they sift through information. I am trying to cultivate a sense of agency in my students, so that they can exercise their own sense of judgment.

COVID-19 has challenged the idea of normalcy. There is no standard any more. We are experiencing the greatest reset of the world. Finally, people have the time to slow down and think about other options, look at things differently. Maybe there is a possibility of realignment so that we all don’t need to go into a crazy direction of who knows where. The situation we are going through now ties in with the idea of Stakeholders. We need to be mindful that we are so deeply, intricately, linked to each other, whether we like it or not, and have more compassion.

Interviewed by Chitralekha Basu

If you go

Shirley Tse: Stakes and Holders

Curated by Christina Li, with Doryun Chong

Dates: Through Nov. 1, 2020

Venue: M+ Pavilion, Art Park, West Kowloon Cultural District

www.westkowloon.hk/en/stakesandholders/shirley-tse-stakes-and-holders