Similarities and differences between Beijing's Palace Museum and the ruins of earlier palatial structures in Anhui are revealing more about little-known periods of history, Wang Kaihao reports.

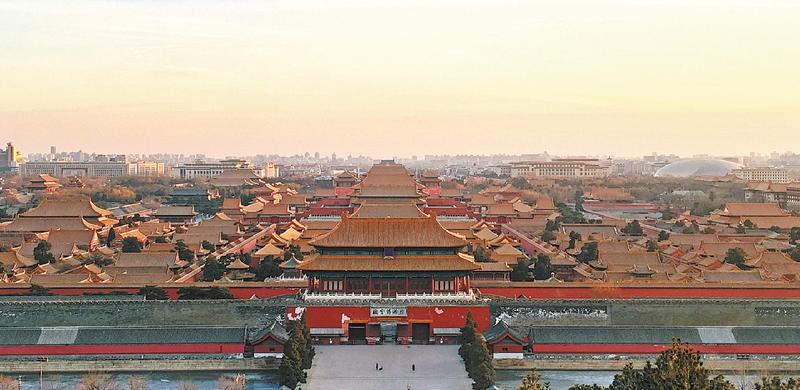

The Forbidden City in Beijing seen from Jingshan Hill. (WANG KAIHAO / CHINA DAILY)

The Forbidden City in Beijing seen from Jingshan Hill. (WANG KAIHAO / CHINA DAILY)

Editor's Note: 2020 marks the 600th anniversary of the founding of the Forbidden City in Beijing, China's last imperial palace. China Daily journalists will talk with researchers and scholars this year to chronicle the history and legends surrounding this architectural splendor that houses over 1.86 million cultural relics.

How many "forbidden cities" are there in China? Several. And their similarities and differences are shedding light on ancient mysteries as excavations uncover them.

For centuries, the Forbidden City, officially known as the Palace Museum today, has stood in the heart of Beijing and witnessed the rise and fall of dynastic power and the nation's ongoing rejuvenation.

This roughly 720,000-square-meter compound that served as the imperial palace from 1420 to 1911 is also the world's largest surviving palatial complex.

But the prequel to this architectural splendor, hidden about 1,000 kilometers away in Fengyang county, Anhui province, is much lesser known worldwide, although it was inscribed on the list of key heritage sites under national-level protection as early as 1982.

The Ming Dynasty (1368-1644) Zhongdu (literally, the central capital) site could be thought of as "the Forbidden City 1.0".

As the Forbidden City in Beijing embraces the 600th anniversary of its founding this year, archaeologists' shovels will gradually reveal more remarkable facades of the Anhui site.

After several months of suspension due to the COVID-19 outbreak, a new round of archaeological excavations on the site resumed in late May.

Since 2017, scholars from the Palace Museum in Beijing have joined the Anhui Provincial Institute of Cultural Relics and Archaeology and several other institutions to conduct research at the site, which the founding Ming emperor originally planned as his capital.

The 840,000-square-meter imperial city in Zhongdu is slightly bigger than its younger cousin in Beijing. Its construction began in 1369, one year after the Ming Dynasty's founding.

Soon after Zhu Yuanzhang, who was once a poor peasant, toppled the ethnic Mongolian Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368) in China and built up his own empire, he decided to make his hometown the national capital.

An ambitious urban-infrastructure project began, and the emperor later bestowed the auspicious name Fengyang (literally, a rising sun like a flying phoenix) upon his home county.

Wu Wei, the archaeologist from the Palace Museum in charge of the excavation, says a much larger outer city was then planned around the palatial section.

A bird's-eye view of the Zhongdu site in Fengyang county, Anhui province. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

A bird's-eye view of the Zhongdu site in Fengyang county, Anhui province. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Archaeological investigation shows the city could cover 50 square kilometers, including military facilities, temples, mausoleums and nobles' residential areas in addition to the palatial compound.

"Zhongdu plays a crucial role in the history of China's urban development," Wu tells China Daily.

"It inherited elements and mentalities from previous dynasties. And its layout, in particular, contributed to the later period. It drew a blueprint for the Forbidden City."

According to Ming Shilu (The Veritable Records of the Ming)-the comprehensive imperial annuals written by historians during the dynasty-a map of the imperial city of the Yuan Dynasty in Beijing (known during the Yuan Dynasty as Dadu, or Khanbaliq) was offered as a tribute to Zhu Yuanzhang in 1369 as a reference to construct his own capital.

"From the design locating palaces along the city's axis to the three-layer structure-the outer walled city, the forbidden city and the palatial city-we can see the layout of Zhongdu was derived from Dadu," Wu explains.

The core palatial section has been the focus of archaeological research.

The earliest archaeological investigation of Zhongdu was conducted from 1969 to 1981 by late archaeologist Wang Jianying, who helped people to recognize the site's significance.

Large-scale excavation began in 2014, as the Zhongdu site was designated as Anhui province's first archaeological park to promote public awareness of heritage protection and tourism's benefits to the local economy.

"Our investigations have covered most areas within the (Zhongdu) 'forbidden city', and we know the layouts of its major buildings, roads and waterways," Anhui Provincial Institute of Cultural Relics researcher Wang Zhi says.

"And our understanding of their construction methods are also improving. We've thus gathered precious experience doing research on other large-scale heritage sites.

"We can't protect Zhongdu as a cluster of individual spots. Only when its integrity is well preserved can its historical significance and connection with the environment be better revealed."

Indeed, more similarities among the palace compounds in Zhongdu and Beijing may become apparent as excavations of the greater area around Zhongdu proceed.

For instance, there's a hill to the north of the palatial city of Zhongdu. Likewise, Jingshan Hill is just across the road from the northern exit of the Palace Museum today. Jingshan Hill was created from earth piled up while digging the moats surrounding the Forbidden City.

The Zhongdu site hosts counterparts of Beijing's Forbidden City's major outer city gates-the Eastern Prosperity Gate, the Western Prosperity Gate, the Meridian Gate and others.

And an area by the southern entrance of Zhongdu's imperial city was cleaned up in 2018, unveiling Chengtianmen (the Gate of Accepting the Heavenly Mandate).

An excavated corner of the constructional foundation of the "No 1 Palace" at the Zhongdu site (left); Wu Wei, an archaeologist from the Palace Museum, does research at the Zhongdu site. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

An excavated corner of the constructional foundation of the "No 1 Palace" at the Zhongdu site (left); Wu Wei, an archaeologist from the Palace Museum, does research at the Zhongdu site. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

There's a similar structure in Beijing, which was renamed Tian'anmen (the Gate of Heavenly Peace) in 1651.

Some local legends say there were "five dragon bridges" underground in the area, but Wu's team found seven.

The bridges also have famous counterparts in front of Tian'anmen, known as Jinshuiqiao.

Though information about Zhongdu's city gates is clearly recorded in history, detailed information about its inner palaces are vague.

"We feel like we're filling in voids in history," Wu says.

"No 1 Palace"

Since September, the archaeological team has dug deeply in the core of the palatial city to further scrutinize connections between Zhongdu and Beijing's Forbidden City.

The ongoing excavation is on the ruins of Zhongdu's "No 1 Palace".Although no hints have been found to its specific historical name, its location is presumably on par with the "three great halls" in its Beijing counterpart.

The so-called "three great halls "on the axis of the Forbidden City's outer section include the Hall of Supreme Harmony, the Hall of Central Harmony and the Hall of Preserving Harmony. The first hall is the highest-status structure in the Forbidden City. It was only used for the most important ceremonies during the imperial era.

"We've figured out the basic H-shaped layout of (Zhongdu's) palace grounds, which is similar to the Forbidden City," Wu says.

"The craftsmanship used to create the stone foundations in the two places is also alike."

But differences have been discovered, too.

For example, remains of a corridor were found in the western wing of the northern part of the "No 1 Palace". Some speculate these belonged to the "Hall of Preserving Harmony".

A firewall stands at the same location in the Forbidden City, but Wu explains that the wall was added during the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911), and the original layout during Ming Dynasty matched this new finding in Zhongdu.

However, there doesn't seem to be a Forbidden City equivalent to a wall with three gates 20 meters north of Zhongdu's "No 1 Palace".

One of the three biggest pillar cornerstones discovered at the Zhongdu site. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

One of the three biggest pillar cornerstones discovered at the Zhongdu site. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

And even more confusing is that no structure similar to the Hall of Central Harmony has been discovered in Zhongdu.

Researchers wonder if Zhongdu also hosted "three great halls".

Only more excavations can reveal relevant clues, Wu says.

Unfulfilled ambitions

Zhu Yuanzhang's ambitious project of turning his hometown into a national capital was never realized.

According to History of Ming, the official historical record compiled during the Qing Dynasty, the emperor once "sat in the palace", indicating some structures were completed and even put to use, but it's unknown whether or not the "No 1 Palace" was finished.

Nevertheless, the emperor changed his mind and eventually halted the construction of Zhongdu in 1375. A common explanation is that the construction was too expensive.

A hint to this may be the 2.7-meter side lengths of three granite cornerstones supporting pillars, which makes them the largest pillar cornerstones ever found in China, according to Wang, the researcher.

By comparison, the side lengths of the largest known pillar cornerstones in the Forbidden City are 1.6 meters.

"Pillar-cornerstone sizes determine the sizes of the entire structures," Yang Xincheng, an ancient architecture researcher with the Palace Museum, says during a visit to the Zhongdu site.

"And the decorative reliefs on foundations and railings in Zhongdu look more complicated than in Beijing. A glimpse is enough to predict that the city could have been more extravagant than the Forbidden City if its construction was completed."

When the emperor returned to Fengyang and inspected the construction site of his future palatial city, he had second thoughts, Yang says, citing Ming Shilu. It's estimated over 1 million people participated in Zhongdu's construction.

"Zhu Yuanzhang used to be poor, and he once mentioned that he tried to distance himself from ostentatiousness," Yang says.

"For example, he ordered the decorative pavement patterns to be simple rather than ornate."

The city was rising in the most glamorous way imaginable before his eyes.

It's still unknown exactly why he abandoned it.

"It'd be an even bigger waste to just abandon a half-constructed city, wouldn't it?" Wang Zhi says.

"So, the common explanation is not sufficiently convincing."

History of Ming suggests the emperor once heard brawling on the roof when he inspected a palace.

His adviser told him that the overworked craftsmen had used necromancy to curse the palace as a silent protest. The emperor decided to move because of this omen, according to this account.

Nanjing, which is today's capital of Jiangsu province, became the emperor's alternative as the national capital.

Tiles unearthed in the "Jinshuiqiao" area of Zhongdu feature dragon and phoenix patterns. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Tiles unearthed in the "Jinshuiqiao" area of Zhongdu feature dragon and phoenix patterns. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Zhu Yuanzhang ordered builders to prioritize stability instead of luxury in his "Forbidden City 2.0" there. His son, Zhu Di, the third Ming emperor, inherited that principle. Zhu Di, who previously resided in Beijing as a prince, won a civil war in 1402 and moved the national capital to his home city.

After massive construction starting from 1417 and lasting for three years, the "Forbidden City 3.0" in Beijing was finished, and the city became the Ming capital a year later.

However, its predecessors, including the abandoned one in Fengyang and the completed one in Nanjing, both crumbled in the following centuries, as continuous wars and social upheavals destroyed most aboveground structures.

Wider horizons

Wu and Yang agree that the fact that there's little archaeological evidence related to the Forbidden City's infancy makes doing research in the Palace Museum difficult.

"Just like ordinary people decorate their new homes, Ming and Qing emperors kept renovating and redesigning the palaces," Yang says.

"Many buildings in today's Palace Museum were rebuilt during the Qing Dynasty, partly due to fires throughout history. And most remaining Ming structures like the Hall of Central Harmony are from the dynasty's middle or late periods."

The surviving imperial Ming court files are also scarce. So, the Forbidden City's earliest history is mostly sealed underground, Yang points out.

"Fortunately, the Forbidden City is very well preserved as a zenith of Chinese palace construction," Wu says.

"However, because it's so intact, we rarely have the chance to conduct underground excavations on the (UNESCO) World Heritage site. After all, we can't demolish those buildings.

"But Zhongdu presents a perfect specimen to understand the Forbidden City's early-period layout, craftsmanship and design due to their similarities. And the Forbidden City also largely guides our research in Zhongdu."

For instance, laboratories in the Palace Museum now perform comparative analyses of artifacts from Zhongdu and their counterparts in the museum.

"They're mutually referential. They help us portray a fuller picture of this chapter of the story of ancient Chinese palatial cities," Wu says.

Contact the writer at wangkaihao@chinadaily.com.cn