Global warming migrates tropical corals to subtropical regions like Hong Kong. However, corals in Hong Kong and Shenzhen suffer Pearl River effluents, discarded fishing nets, as well as typhoons. Marine scientists of both regions are collaborating to improve the current situation. Shadow Li reports.

Preserving marine ecosystems

Coral reefs are the “tropical rain- forests” of oceans, providing food and shelter to 25 percent of marine creatures. Their loss would remove an essential home for marine flora and fauna, and further diminish the already paltry undersea resources of Hong Kong waters. Are we doing enough to protect our marine habitat and its life forms?

The discharge of the Pearl River around Shenzhen and Hong Kong, especially along the western shore, is turbid with low salinity. It is not optimal for coral species. Most of the coral able to survive under these conditions would be stony coral.

Shenzhen’s Dapeng peninsula, a few kilometers from Hong Kong’s Tung Ping Chau Marine Park, hosts almost all the corals found in Shenzhen. And Tung Ping Chau has 65 of the 84 coral species found in Hong Kong. Minimal human disturbance allows corals in Tung Ping Chau to survive better than that at Mirs Bay off Dapeng peninsula in the same bay.

It seems logical that marine scientists in both territories collaborate to share knowledge, techniques, and resources. Unofficial contact between volunteers and scientists has evolved across the bay in recent years although the official co-ordination is lacking. David Baker, assistant professor at the University of Hong Kong, commented that corals and waters do not have boundaries.

![]()

Artificial breeding

Guangdong province formed a team of scientists and volunteers in 2007 to conduct an annual July-November audit of coral life. Liao Baolin, secretary-general of China Reef Check, is worried about the high rate of coral-destruction. Data for the past 30 years shows an alarming-drop in coral coverage in Shenzhen as it has been slashed in half to about 30 percent in recent years.

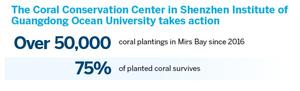

Liao is director of the Coral Reef Conservation and Rehabilitation Research Center at the Shenzhen Institute of Guangdong Ocean University. He is leading efforts to rescue coral colonies. Coral polyps are animals in the phylum cnidaria family, with photosynthesis algae “zooxanthellae” inside them.

Rehabilitating corals can be either by sexual or asexual propagation. Sexual propagation requires capture of the annual spawn season, which is usually during a full-moon night in summer. The process of settlement after mixing for fertilization into larvae on a substrate to grow into coral polyp has a low success rate. Much of that is still in laboratories.

Sexual propagation

Sperm and eggs from corals merge to form new individuals.

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Asexual propagation involves chipping a coral polyp to transfer to a coral nursery. At an appropriate point of growth, the coral buds would be transplanted to 120 artificial coral reefs in the sea, maintained by the Dapeng Linhai Marine biological industry innovation demonstration base. Each coral reef would average a density of 300 coral buds.

Asexual propagation

A piece broken off from parent corals can mature and start new colonies. These colonies will be genetically similar to the parent. A disadvantage is the reduced genetic variability.

![]()

![]()

![]()

Asexual propagation is also the option used in Hong Kong. The city’s Agriculture, Fisheries and Conservation Department (AFCD) commissioned scientists from the University of Hong Kong to rehabilitate coral colonies of the Hoi Ha Wan Marine Park, which suffered extensive damage in 2015 and 2016.

Marine biologist Apple Chui Pui-yi followed natural fertilization by culturing coral larvae from Tolo Harbour in a lab-based nursery. Tolo Harbour had abundant corals in the 1980s that were killed off by pollution and sediment from urbanization.

Reef Design Lab, an Australia non-profit, used a 3D-printed Modular Artificial Reef Structure to anchor the world’s biggest artificial reef frame in waters off the Maldives, to encourage coral larvae to settle there. The SAR government is mulling a similar 3D printed framework to rehabilitate coral colonies in Tolo Harbour.

Natural habitat

The optimal temperature for healthy coral is within 25 to 28 C. That pertains in coral colonies of the Philippines, for example, where the temperature and abundant sunlight breed corals naturally with minimal climatic stress. They regenerate when detached by storms or fishing nets, as the larger ecosystem supports re-growth.

![]()

Xia Jiaxiang, a worker for Dive4Love, an NGO in Shenzhen that helps conserve coral, disagrees with the cutting off of coral fragments for asexual propagation. After seven years of diving to check the coral reefs cover, he is not convinced.

“Shenzhen is in the subtropical region, far north of the natural habitat of coral reefs. That makes it almost unsuitable for corals. If we cut off parts of corals, which are already in a fragile state, do we protect or do more damage?” asked Xia.

Xia and his colleagues retrieve only portions of corals detached by fishing nets or storms, which they place in a plastic cage above the seabed to protect them from sea urchins and sand movement. That places the coral fragments closer to the sea surface for better sunlight to accelerate photosynthesis for survival. When the corals thrive, they remove the plastic cage and return the regenerated coral to the ecosystem of the sea.

Xia is despondent about the long-term future of the coral colonies. He thinks coordinated action on human activities, effluent discharge, plus regeneration measures at sea are needed to conserve the coral, beyond just one or two isolated initiatives.

Coral migrates

A Marine Ecology Progress Series study in July noted that warming oceans have been migrating corals from the equator into subtropical waters over the past 40 years. The six-country team of scientists have observed the number of young corals on tropical reefs declined by 85 percent, but doubled in subtropical waters.

Lead researcher Nicole Price, US-based Bigelow Laboratory for Ocean Sciences, said as climate change warms the oceans, subtropical environments are becoming more favorable for coral than the equatorial waters where they traditionally thrived. This allows drifting coral larvae to regenerate in new regions. These subtropical reefs could provide refuge to other species challenged by climate change, as fledgling ecosystems.

Global warming is considered one of the key factors that gives stress to corals by exhausting the symbiotic algae, which then leads to bleaching. It is a temporary condition that can recover if such stress abates. A two-year study of Hong Kong’s coral colonies by the AFCD and local scientists, released in October, revealed that the corals at six sites that suffered bleaching fully recovered within one to three months.

The study’s leading scientist, Qiu Jianwen, at Hong Kong Baptist University, said warmer weather in Hong Kong seems to favor certain types of corals. He said signs of coral migration to subtropical areas like Japan has been found, though not yet in Hong Kong. 2019 was the warmest year for Hong Kong since 1884, with temperature averaging 24.5 C.

Last year saw the highest number hot nights with 46, a 77 percent increase from 2018. “Hot nights” are days with the lowest temperature of the day over 28 C. One cold day with the lowest temperature below 12 C was recorded for the year. Reef-building corals grow optimally in water temperatures between 25 to 28 C.

CO2 acidification

Liu Sheng, researcher at the South China Sea Institute of Oceanology of the Chinese Academy of Sciences, wonders if global warming is making the Greater Bay Area a more suitable place for corals. Corals in the Greater Bay Area are no longer forming extensive carbonate reef systems; instead, they form colonies in shallow coastal waters, said Liu.

Some scientists noted the Greater Bay Area might attract migrating corals with global warming. But global warming creates excess carbon dioxide that could acidify the seawater and dissolve the calcium in corals skeletons. Liu wondered if the temperature peaks may be followed by adverse acidification of seawater.

At present, the average temperature of seawater in Shenzhen and Hong Kong is around 25 C. However, when the cold currents strike, it could dip to 13 C, which threatens corals life. This lack of a stable, year-round temperature is another challenge for the coral colonies of Shenzhen and Hong Kong.

Net & typhoon damage

Over his many dives, Xia finds that abandoned and drifting fishing nets is a constant danger to the coral colonies. Xia tries to alert and educate the fishing community of Dapeng to not discard their nets in the sea. That is moral persuasion only. Monetary incentives may be more effective but are not available yet.

Corals breed within 6 meters of the seashore, which is the impact range of the annual typhoons. In a typhoon-prone zone like the Greater Bay Area, extreme weather threatens the survival of corals. Xia said human beings adversely impact the ecology for corals, and reduce their chances for survival, on top of global warming and typhoons.

Contact the writer at stushadow@chinadailyhk.com

![]()