Top scientists gather in Guangdong province for a milestone project to explore the universe’s mysteries. As Li Bingcun reports, the China-led initiative has become a testament to the power of international cooperation in driving scientific progress.

Editor’s note: In the vibrant Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Greater Bay Area, future-oriented innovations are the driving force behind rapid development. This series identifies major scientific breakthroughs and the facilities that support these innovations, with the third article focusing on the international collaboration fostered by a world-leading physics experiment.

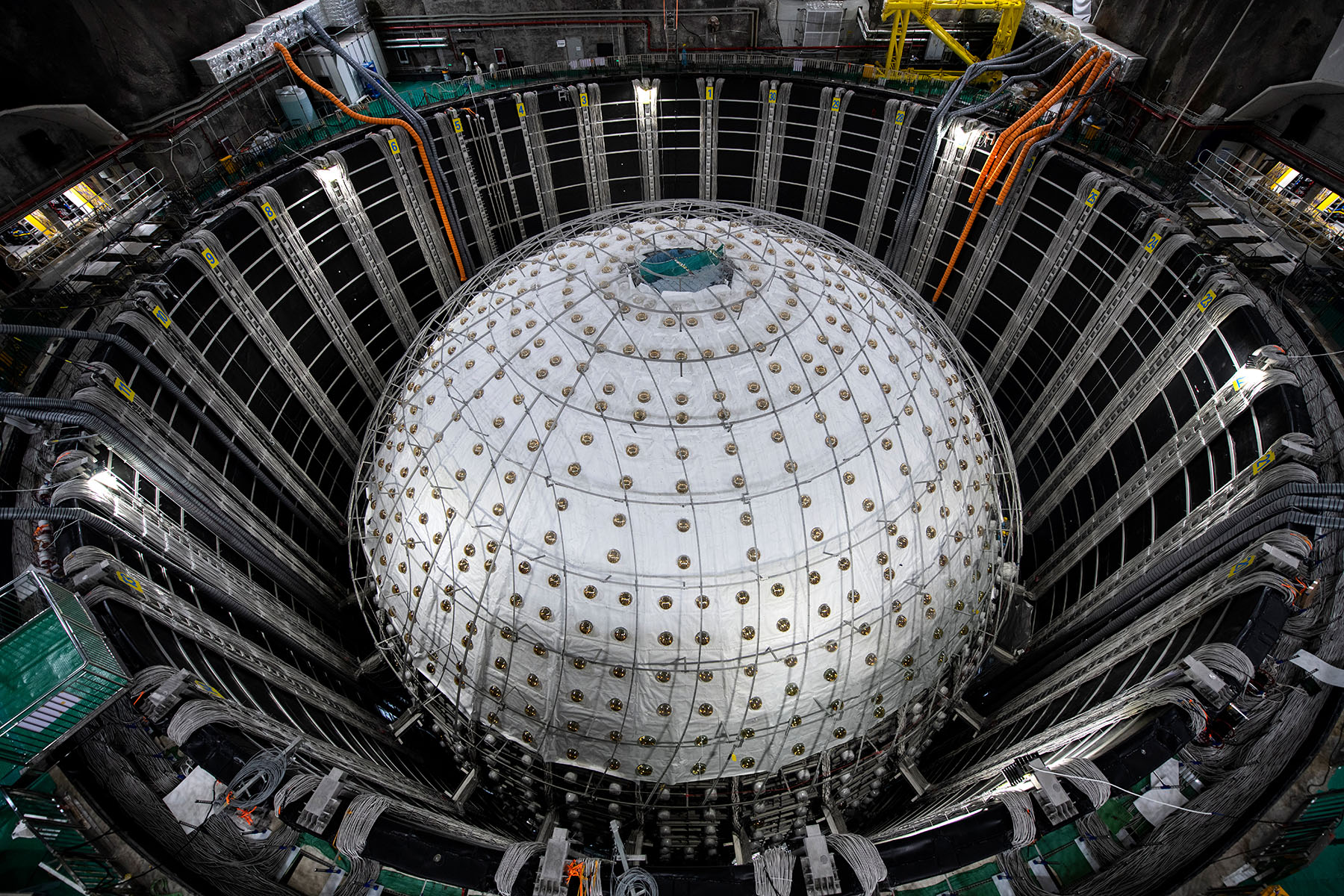

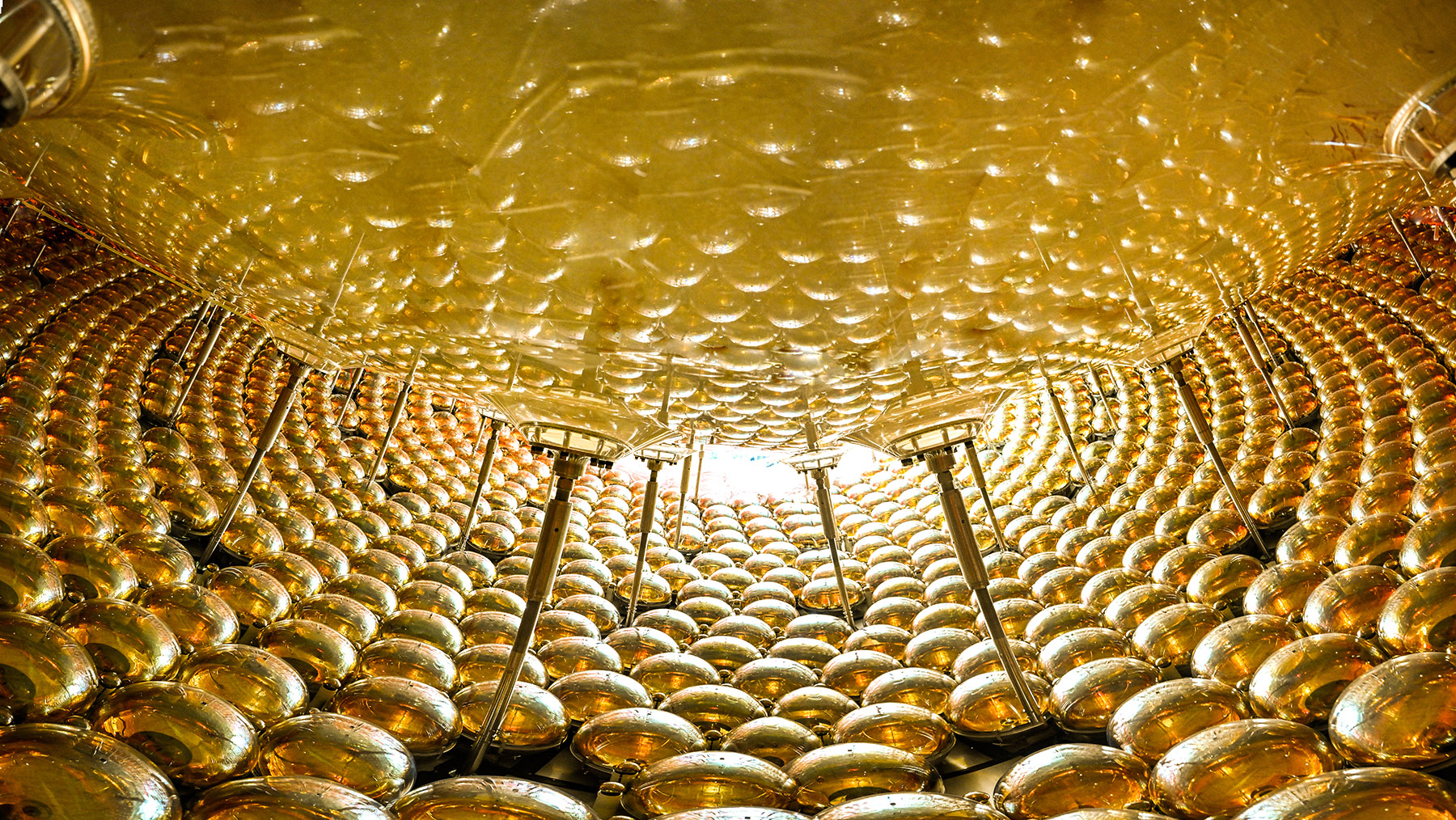

Seven hundred meters beneath the surface of Jiangmen city in South China’s Guangdong province, and accessible via a 15-minute cable car ride on a sloping tunnel, scientific equipment from various countries has been used to create the Jiangmen Underground Neutrino Observatory — a colossal world-class underground facility that explores the mysteries of the world’s origins.

On the ground, dozens of international scientists gathered to witness the release of the project’s first research results — a milestone for a large-scale detector that may reshape global foundational scientific research in the decades ahead.

With a design and construction period spanning over a decade, the underground engineering marvel features a massive spherical detector with ultra precision. Spanning 41 meters in diameter, it’s equipped with 45,000 photomultiplier tubes surrounding 20,000 metric tons of liquid scintillator. Located 53 kilometers away from two nuclear power plants in southern China, the detector is perfectly positioned to capture neutrinos emitted from these facilities.

READ MORE: JUNO yields first results, searches for 'new physics'

As fundamental particles, neutrinos are tiny and near massless, traveling near the speed of light. They hold the key to unraveling crucial physics mysteries like the origins of matter, the Earth’s structure, stellar evolution, and exploring new physics beyond the standard model of particle physics.

On Nov 19, just two months after the project began operations, the international research team led by the Institute of High Energy Physics (IHEP) of the Chinese Academy of Sciences released its first research results, revealing that the detector had fully met design expectations, preparing the observatory for advanced research in neutrino physics.

Bringing together the expertise of more than 700 scientists from 75 institutions across 17 countries and regions, JUNO is an upgrade to and extension of the previous Daya Bay neutrino detection program, and is one of the largest international fundamental science cooperation projects led by China. Aimed at measuring the neutrino mass ordering and oscillation parameters, the facility is designed for a scientific lifetime of about 30 years.

Marcos Dracos, a French physicist who chairs the JUNO Institutional Board and has participated in many similar experiments, says they’re “nothing compared to JUNO”, in terms of the size of the collaboration, the scale of the detector or the overall research context.

Unlike previous projects that already had substantial infrastructure in place, JUNO required everything to be built from scratch, from underground caverns to a complete experimental setup.

On his first visit to the proposed experiment site in Jiangmen’s rural expanses in 2014, marking the inception of international collaboration, Dracos found himself “essentially in the middle of nowhere”, walking along a narrow path flanked by chickens and buffaloes — a far cry from the infrastructure that exists today.

Besides China’s, other new-generation scientific experiments, such as Japan’s Hyper-Kamiokande and the United States’ Deep Underground Neutrino Experiment (DUNE), also focus on neutrino studies and are expected to start operating from 2027 through 2030.

Dracos’ research team ruled that JUNO offered the right opportunity to make substantial progress in neutrino oscillations. As only those who have contributed to the project’s construction can utilize it for research, building such an advanced detector also presented opportunities for international engineers and technicians to develop new techniques at the forefront of the current technology, says Dracos.

Bob Hsiung Yee, chair professor of Department of Physics at National Taiwan University, hails the international scope of the Jiangmen experiment that harnesses the scientific expertise of multiple countries.

A global endeavor

Led by China’s IHEP, the project involves numerous Chinese mainland universities, as well as research organizations from Europe and beyond. About one-third of the research members are from overseas, contributing approximately 10 percent of the facility’s construction funding.

Italy invested a significant effort in JUNO’s liquid scintillation system, while France contributed its expertise in a cosmic muon tracking system and a sealed electronic system. With its background in accelerator and neutrino experiments, the IHEP has considerable specialization in detector design.

“The only area in which no one has expertise is how to dig down 700 meters underground,” Hsiung says in jest. It took six years from 2015 to carve out the laboratory in a deep, water-rich environment, presenting the biggest challenge in the project’s initial phase.

With the goal of addressing challenging scientific questions, researchers found that their major obstacles were largely unrelated to science. This remained the case throughout the following four years spent building the detector from 2021 to 2024, Dracos recalls.

At the height of the COVID-19 pandemic, overseas scientists were forced to work remotely. They had to rely heavily on available communication technologies, and did everything possible off-site to continue preparing the experiment.

After normal international interaction resumed, foreign scientific institutions shipped equipment to Jiangmen and sent technicians, engineers and researchers to participate in the detector’s construction that required considerable effort.

He Miao, a researcher at IHEP, is responsible for the construction of JUNO’s small photomultiplier tube system, along with scientists from various countries. His team is one of the most internationalized groups involved in the project.

Similar to drifting particles in the universe, the team’s members come from different backgrounds and have varied work rhythms and styles. Under the project, they worked together deep underground, climbing onto the detector framework to test equipment. They addressed time differences in countless online meetings to discuss work, and explored future multinational collaboration in other areas of high-energy physics.

In the subsequent research phase, there will be internal competition regarding whose results should take precedence in publications. However, all contributions will be shared, and everyone in the collaboration will be acknowledged as co-authors, listed alphabetically by their surnames.

Connected by their passion for physics, the scientists established friendships through this great project. They treated each other to local delicacies, such as Jiangmen’s famous roast pigeon and French family cuisines. During the pandemic, He donated masks to his European colleagues who were in urgent need of medical supplies.

“We all think the device is exceptionally well-built and advanced. I can truly feel their joy and pride (to be participating in this project). This experiment also serves as a window for them to gain insights into China’s scientific spirit and research prowess,” he says.

After lengthy preparations, including some unexpected delays, the physicists were eagerly awaiting the first data, not only to extract the initial physics results, but also to confirm that their expectations were met and their work correctly accomplished.

The quality of the initial results, obtained in such a short time, fully validated their efforts. “It’s extremely satisfying to see that all the years invested in preparing the experiment have been truly worth it,” says Dracos. It was the first time for many European scientists to be busy for such a long period in a Chinese project, far from home. They adapted themselves to the challenges and it has been a remarkable and rewarding experience, he says.

Following the Daya Bay and JUNO projects, China has firmly established itself at the forefront of fundamental physics, and strengthened its advanced manufacturing and research and development capabilities.

“Hosting such world-leading international experiments has enhanced China’s reputation as a global center for cutting-edge research, attracting top talent and fostering international collaboration. It also serves as a training ground for a new generation of scientists and engineers working on frontier technologies and big-data analysis,” says Dracos.

“JUNO broadly reflects China’s long-term strategy to evolve from a follower to a leader in foundational scientific discovery — a transition that can yield unforeseen technological benefits in the future,” he says.

Science without borders

From the day fundamental science was born, it has been a collaborative effort among scientists worldwide, and all significant results receive recognition from the global scientific community. The best way to achieve this recognition is to involve them directly in the work, says He, explaining the motivation for the IHEP to initiate international collaboration in this project.

Such an approach is common practice in large-scale experiments around the world. Japan and the US have their latest neutrino experiments involving 11 and more than 30 countries, respectively. Experiments at the European Organization for Nuclear Research attracted 12,000 scientists from more than 100 countries, representing half of the world’s particle physicists.

Through international collaboration, China’s large scientific facilities have achieved significant results. The new mode of neutrino oscillation discovered by the Daya Bay neutrino experiment was ranked among the top 10 scientific breakthroughs of 2012 by Science magazine. Additionally, the Five-hundred-meter Aperture Spherical Telescope in China’s Guizhou province collaborated with the Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope launched by the US to discover over 50 millisecond pulsars.

The scientists emphasized that only breakthroughs in fundamental research can foster the sustained development of applied sciences. The outcomes derived from the two revolutionary theories of modern physics — relativity and quantum mechanics, both introduced in the early 20th century — have been leveraged for over a century. Fundamental science is in urgent need of new breakthroughs to drive future advancements.

And deepening scientific research has placed higher demands on scientific instruments and experiment design. “The easier high-energy physics experiments are mostly finished, and could be completed in a few months. The remaining ones are more challenging, and may take decades yet,” says Hsiung.

Compared to going it alone, international collaboration can pool the best resources and technologies, resulting in outcomes that surpass expectations. While it may require more effort for coordination, the potential breakthroughs it could offer are substantial, he says.

Meanwhile, global economic uncertainties and geopolitical tensions have slowed transnational scientific research collaboration, including the closing of research branches, diminishing funding, and increased scrutiny on scientific exchange activities. As the saying goes, “while science knows no borders, scientists do have national affiliations”, the differing positions among researchers may also hinder communication.

The JUNO participants hope the situation is only temporary, believing that collaboration is an inevitable trend. Even if economic activities begin to decouple and certain applied technologies face overseas blockades against the deglobalization backdrop, foundational research cooperation must continue for the lasting welfare of humanity, they say.

ALSO READ: JUNO, underground eye on the universe, starts operation in Jiangmen

With JUNO’s first research results, the international teams have officially begun their explorations. The facility aims to measure neutrino mass ordering within about six years, after which it will enter a new research phase that may offer new opportunities for external collaboration.

Hong Kong scientists are also welcome to join, continuing the partnership from the Daya Bay project.

At 72 and with two decades of involvement in the Chinese mainland’s neutrino experiments, Hsiung, who has retired, says he will continue to participate in the JUNO experiment to await the final results.

Although physicists may only study a few significant questions in their lives, and sometimes breakthroughs require an element of luck, the scholar from China’s Taiwan remains drawn to the allure of pursuing new frontiers.

Humanity’s knowledge of the universe remains exceedingly sparse, and only collective efforts can help form a broader picture, he says.

Contact the writer at bingcun@chinadailyhk.com