Rare manuscripts, heirloom relics and imperial records unite in a centennial exhibition in Beijing, Wang Ru reports.

Emperor Qianlong of the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911) formalized a New Year's tradition during his 64-year reign. On the eve of every Chinese New Year from 1736 to 1799, at the quietest moment of midnight, he performed a private ritual in the eastern chamber of the Yangxin Dian, or Hall of Mental Cultivation, in the Forbidden City.

Alone, away from the grand spectacles of court ceremony, the monarch lit a solitary candle, picked up his brush, and recorded his hopes for peace, prosperity and harmonious governance on a simple piece of yellow paper. First, he wrote a bold line of vermilion characters along the center, then added carefully measured black ink characters on either side. After completing each manuscript, Qianlong placed it into a box, never to be shown to others. Only then did he sip a cup of Tusu wine, a traditional medicinal wine believed to ward off misfortune.

READ MORE: A real gem of a story

More than two centuries later, many of those manuscripts still survive, delicate remnants of an emperor's private moments of contemplation. Several of them are now being exhibited for public viewing at the First Historical Archives of China in Beijing. Alongside them is another manuscript written by Qianlong's son and successor, Emperor Jiaqing, who ruled from 1796 to 1820.His detailed record of the ceremony provides modern historians with rare insight into this imperial ritual.

The combination of archives and artifacts, such as a pen, a candlestick and a cup used by emperors specially for this ceremony, is highlighted at the exhibition Rui Yi Shi Quan (Perfect Ten): A Joint Showcase of Imperial Archives and Treasures, which kicked off on Oct 11.

Jointly organized by the Palace Museum in Beijing and the Archives, the exhibition commemorates the centenary of both institutions, which have a shared origin.

On Oct 10, 1925, the Forbidden City, the former imperial complex of the Ming (1368-1644) and Qing dynasties, was transformed into a public cultural institution known as the Palace Museum. Its literature department, then responsible for managing the historical archives the Qing court left behind, has evolved into the present-day First Historical Archives of China, collecting more than 10 million archives from the Ming and Qing eras.

Through a display of 100 archives and artifacts, curators tell stories of 10 positive aspects of individual life, society, and even the nation. These include achievements in keju, or the imperial civil service examination system, the bond of friendship, the pursuit of health, and festive celebrations in the Qing court. The narratives are brought to life by presenting these closely related artifacts and archives.

"The positive aspects symbolize people's enduring aspiration for a good life. Thus, we have chosen this timeless and universal theme to celebrate the 100th birthday of both institutions," says Wang Jinlong, deputy director of the First Historical Archives of China.

For instance, the exhibition showcases a grand ceremonial robe once worn by Emperor Kangxi, who reigned from 1661 to 1722, alongside archival records that meticulously document what Emperor Qianlong wore for rituals, banquets and seasonal ceremonies.

"Qing emperors were required to wear different attire for various occasions, often changing multiple times a day. Each change was meticulously documented, creating detailed records of their attire ... We have not yet located such detailed costume records from Kangxi's reign, so instead, we display Emperor Qianlong's to illustrate this extraordinarily meticulous system," says Wu Huanliang, one of the curators of the display.

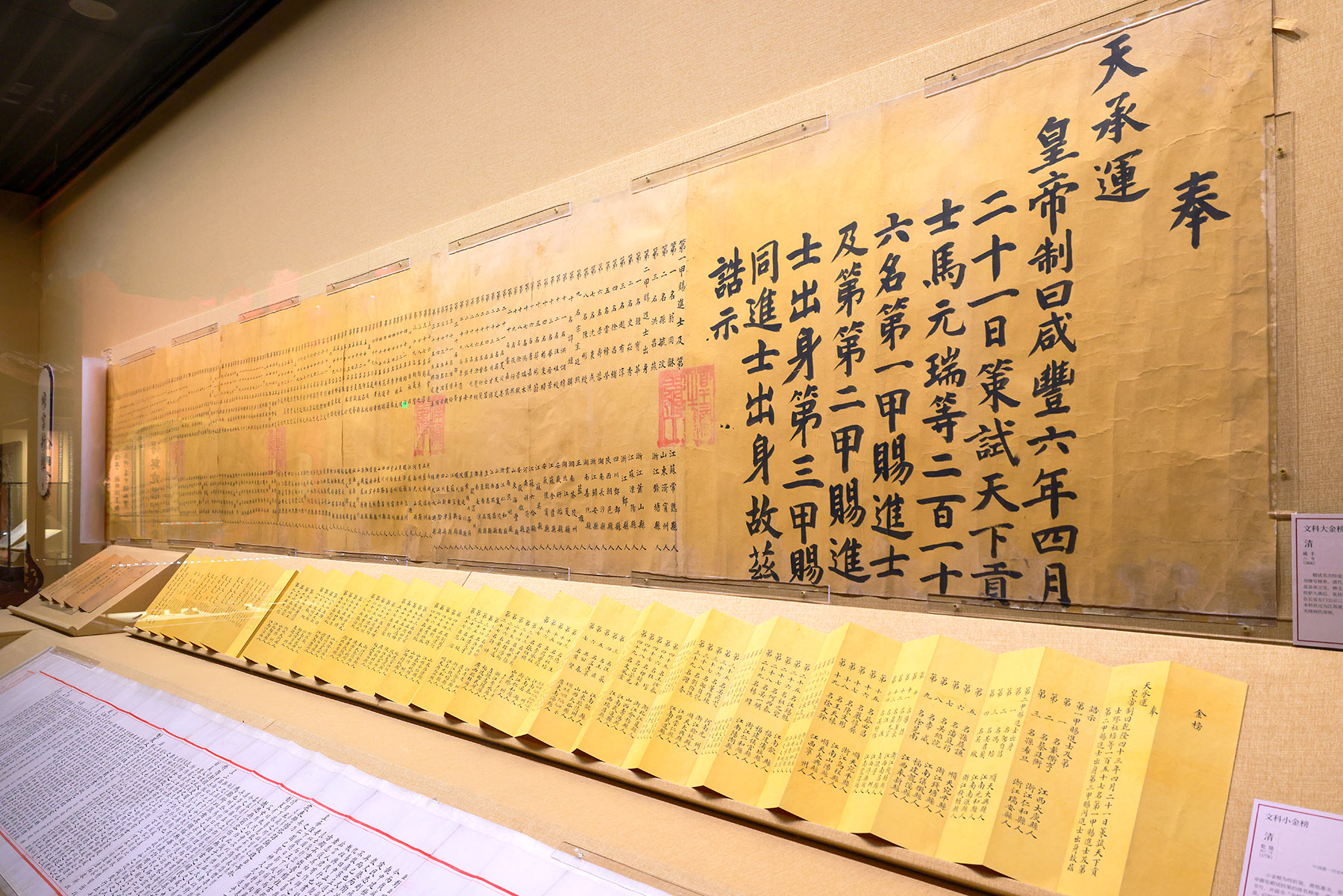

Another gallery in the exhibition celebrates excellence in scholarship through the imperial examinations. Two eye-catching artifacts dominate the space: large and small golden lists announcing the names of candidates who passed the final stage of the Qing examination system. The imposing larger list would once have been pasted on the walls of imperial gates for public viewing, while the smaller version was reserved exclusively for the emperor's desk.

Nearby lies a treasure for both historians and lovers of calligraphy: the original exam paper of Li Wei, who came 11th in the palace examination of 1778 and later became a famous Qing Dynasty painter. Li wrote his answers on this sheet during the dianshi, or palace exam, the final stage of the keju system, which was held in the Qing court and presided over by the emperor himself.

Wu says in earlier stages of the exams, candidates' answer sheets were copied by officials before being presented to examiners, a measure designed to prevent cheating. However, in the final exam, candidates wrote directly to the emperor, who determined their rankings without any filtering. As a result, their calligraphy became an important factor in the evaluation. This answer sheet allows viewers to see Li's authentic handwriting.

The Palace Museum provides a complete set of exquisite stationery used by emperors, and a stone seal engraved with the characters dushule (the happiness of reading) as real objects related to the imperial exam.

The characters come from a set of Song Dynasty (960-1279) poems which urged people to read and learn because the ancient literati prioritized reading and learning diligently in order to participate in keju, showing the influence of the ancient system, Wu says.

According to him, the joint exhibition of cultural artifacts and archives makes up for the shortcomings of both. "Archives offer detail but may lack visual impact. Artifacts are visually compelling but offer little context when seen alone. By presenting both together, we create a complete narrative and help audiences better understand the evolution of Chinese civilization during the Qing period," says Wu.

Wang says the Palace Museum now has a collection of more than 1.95 million cultural relics as of the end of last year, most of which have records in the archives stored in the institution.

ALSO READ: Hidden behind the halls of royalty

"The archives and artifacts are all sourced from the Qing court. They are significant cultural resources. The shared mission of our two institutions is to safeguard these treasures and carry forward the cultural lineage," he says.

The work behind such an exhibition stretches across generations. "With more than 10 million archives in storage, our predecessors spent decades organizing and categorizing them. Today, although not all have been digitized, published catalogs and academic research guide our curation. Every exhibition, every educational program and every cultural product we develop stands on their labor," Wu says.

To celebrate the centenary, another exhibition about the archives' history and a social education space have been opened as well.

Contact the writer at wangru1@chinadaily.com.cn