Independent bookstores in historic hutong foster reading, community engagement, and cultural heritage, offering spaces where literature, creativity, and human connection thrive.

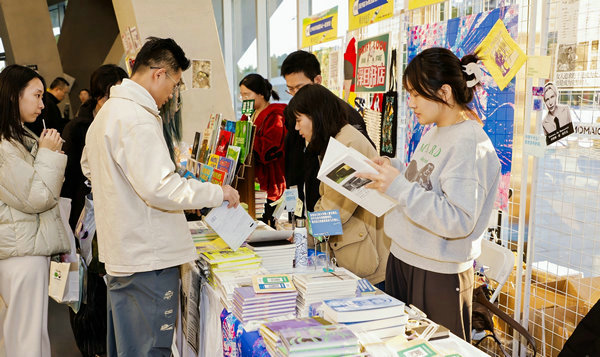

From Oct 16 to 19, the Beijing Book Fair transformed the National Tennis Center from a venue of athletic competition into a celebration of the mind. Now in its 11th edition, the fair brought together more than 300 publishing and creative brands, alongside writers, editors, and film producers.

Beijing's enthusiasm for reading extends far beyond this annual event, with iconic initiatives taking root across the city.

Since 1997, for example, the "Temple of Earth and Me" Beijing Book Fair has been held twice a year, attracting 550,000 visitors this September alone. The city's "15-minute reading circle" now offers access to 6,026 public libraries and reading rooms, as well as 228 self-service libraries open 24 hours a day — reaching communities and villages across Beijing.

But beyond these large-scale efforts, independent bookstores have become vital threads in the city's literary fabric, weaving Beijing's rich reading culture into its historic hutong.

One such example is Possibly Books, a bookstore tucked away in Chaomian Hutong. It was founded in 2023 by Zhao Chen, who left a central state-owned enterprise to return to his childhood neighborhood.

Zhao describes hutong culture ahuts "both delicate and resilient". Here, the walls hold layers of old Beijing's history, and the residents preserve a warmth of human connection that high-rise buildings can never replace — a spirit that permeates his bookstore.

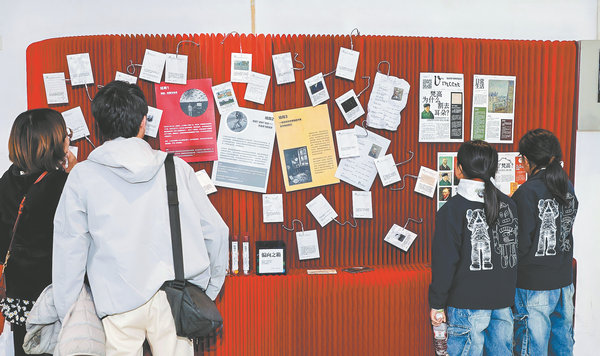

Zhao designed interactive areas where visitors can share their thoughts on books and poetry, and also leave their own verses and reflections in notebooks as traces of themselves.

"It helps people form new social bonds through literature," Zhao said.

Beyond the shop itself, Zhao organizes city walks that follow literary threads, guiding visitors through the surrounding hutong and cultural landmarks. One popular series, inspired by renowned writer Lao She (1899-1966), traces locations from his works and links them to nearby teahouses and historic sites, creating a living map where literature, history, and everyday life meet.

"We even set aside a spot for a retired auntie who lives in the hutong to run a dumpling stall," Zhao said with a smile. "It's not just about food — the stall brings warmth and character to the bookstore."

Adding to the shop's charm are its two feline "employees". Yuanbao is affectionate and observant, often watching quietly from a corner, while Zhaosi is moody and lazy, usually napping when visitors arrive — embodying the cozy, lived-in comfort that makes the bookstore feel like home.

Surrounded by the hutong's timeless lanes, young readers bring their own vitality to the space. Some study quietly as they prepare for exams, while others linger over slim volumes of poetry until dusk. Once, a young man even proposed among the shelves, secretly hiding a ring with Zhao's permission.

"Most young people come for two things: content and atmosphere," Zhao said. "A good book, or a space that sparks new ideas — that's true fulfillment."

Independent bookstores like Possibly Books have become cultural anchors, keeping the hutong spirit alive.

According to the People's Government of Beijing Municipality, the city had fewer than 1,000 physical bookstores before 2016. By 2022, that number had risen to over 2,000, with more than 0.94 bookstores per 10,000 residents — the highest density in China.

From 2016 to 2020, Beijing invested over 286 million yuan ($40.14 million) to support local bookstores. In 2021, the city refined its policy, providing rent subsidies to 148 bookstores and funding 2,151 reading and cultural events organized by 142 of them. Many of these stores are nestled in hutong, including Xuannan Bookstore in Lanman Hutong, Zhengyang Bookstore in Zhuanta Hutong, and Xiaozhong Bookstore in Houyuanensi Hutong.

Among Beijing's many independent bookstores, Wang Hechen, a finance professional at a leading state-owned bank, has a favorite — Wansheng. Founded in 1993 near Tsinghua University, it has long been a haven for serious readers.

"Wansheng, with its focus on the humanities and social sciences, has a real gift for choosing books," he said.

He attributes this to Liu Suli, the bookstore's owner — a Peking University graduate in international politics who has published extensively in social science journals. That background, Wang believes, explains why Wansheng's shelves are filled with a thoughtfully curated mix of academic works, literature, and history titles, often arranged by theme to inspire deeper exploration.

Building thought

While many bookstores today double as cafes, Wansheng serves no drinks — preserving its original, book-centered atmosphere. "Towering shelves full of books surround you, creating a sense of grounded simplicity," Wang said.

For Wang, reading is a discipline — a way to cultivate thought. While many readers focus on an author's conclusions, he is more interested in how the author gets there.

"When I read philosopher Chen Jiaying's reflections on education, indoctrination, and brainwashing, I pay attention to why he connects these ideas and how his reasoning unfolds, rather than the final view he reaches," Wang said. "True reading, to me, means sharpening my own mind through a dialogue with the author."

This outlook also shapes Wang's approach to investment. He sees investing not merely as a matter of finance, but as a way of understanding life — something that numbers alone cannot capture.

He draws inspiration from Poor Charlie's Almanack, a collection of practical wisdom from legendary investor Charlie Munger.

"Munger uses a latticework of mental models — an interconnected framework of ideas from psychology, economics, and physics — to guide his judgment," Wang said. "He examines how each model works on its own and how it fits into a broader system."

Like Munger, Wang looks beyond financial data, turning to history for perspective. An avid reader of works such as Zizhi Tongjian (Comprehensive Mirror to Aid in Governance) by Sima Guang and 1587, A Year of No Significance by Ray Huang, he believes investors — like historians — must understand companies within long-term historical and social cycles.

"When markets are driven by fear, greed, and the chase for instant gratification, these broader insights help you cut through the noise," he said, adding that such a mindset keeps him grounded in value investing even amid shortterm market swings.

The value of paper

For Kong Xinxin, an editor at CITIC Press, Beijing's lively book fairs and cultural salons are more than just professional gatherings — they're opportunities to connect and be inspired.

"Talking with other editors helps us exchange insights, and discussing old and new projects with authors often sparks creativity," Kong said. "Even a bit of casual conversation at these events can leave me overflowing with ideas — it sometimes takes days to process them all."

Kong recalled one fair where she hosted a talk for an author who studies ants — a topic she expected would attract only a small crowd.

"I was surprised to see parents and kids filling the front rows before we even began," she said. "They listened closely, asked questions, and lined up for autographs afterward."

For Kong, the scene was a reminder of readers' enduring curiosity — even for subjects that seem obscure. "As editors, we need to be where the readers are," she said.

In an era dominated by digital media and fleeting short videos — which, she believes, encourage fragmented, image-driven reading habits that can erode patience and focus — Kong sees printed books as more important than ever.

"A book communicates in ways no other medium can," she said. "Beyond sharing knowledge, it trains the mind, sharpens thinking, and invites deep reflection."