Popular cartoon sparks debate about gender roles, family chores

Portraying a three-member household, the award-winning animated series Big-Head Son and Small-Head Dad — first aired in 1995 — is back in the public eye, after sparking fiery debate about gender and family roles.

At the center of the discussions is "Apron Mom", who many critics of the cartoon have pointed out appears to only exist to serve the interests of the father and son.

Social media influencer "Maebo" got the ball rolling on the Red-Note platform in February with her post "Apron Mom, when can you take off your apron?" The post garnered over 47,000 likes, and the trending topic has since led to widespread online discussion about the issue.

After her post went viral, Maebo said several netizens shared scenes from the cartoon that exemplified the problem of the outdated depiction of a mother's role. One of the most widely discussed clips shows Apron Mom fainting while Small-Head Dad rushes over and says: "Apron Mom, you can't die! Big-Head and I haven't had dinner yet!"

"To place an individual's life below the urgency of whether or not dinner is served goes beyond gender," Maebo said, "it becomes a question of basic humanity."

ALSO READ: Male teachers face kindergarten conundrum

In another clip, Big-Head Son announces: "Today is International Women's Day. Let's let Apron Mom rest for one day." Maebo said "rest" is framed as an "exceptional reward "for Apron Mom, with the implication that "not resting is her default duty".

Maebo's posts quickly drew a wide range of comments.

Some pointed out that while the male characters are identified by their physical traits, the mother is defined by an apron, a symbol of domesticity. "It reinforces the idea that her identity is inseparable from her labor," Maebo said.

One English teacher noted that during classroom exercises on occupations, students frequently associated fathers with prestigious jobs such as "doctor" or "engineer", while mothers were more often labeled "cook". The teacher began encouraging students to challenge these assumptions, reminding them that mothers can also be doctors.

Whether humorous or serious, one netizen posted an observation about Big-Head Son's birth, saying, "his head is so large that it must have been a painful childbirth for Apron Mom."

Unwelcome cliches

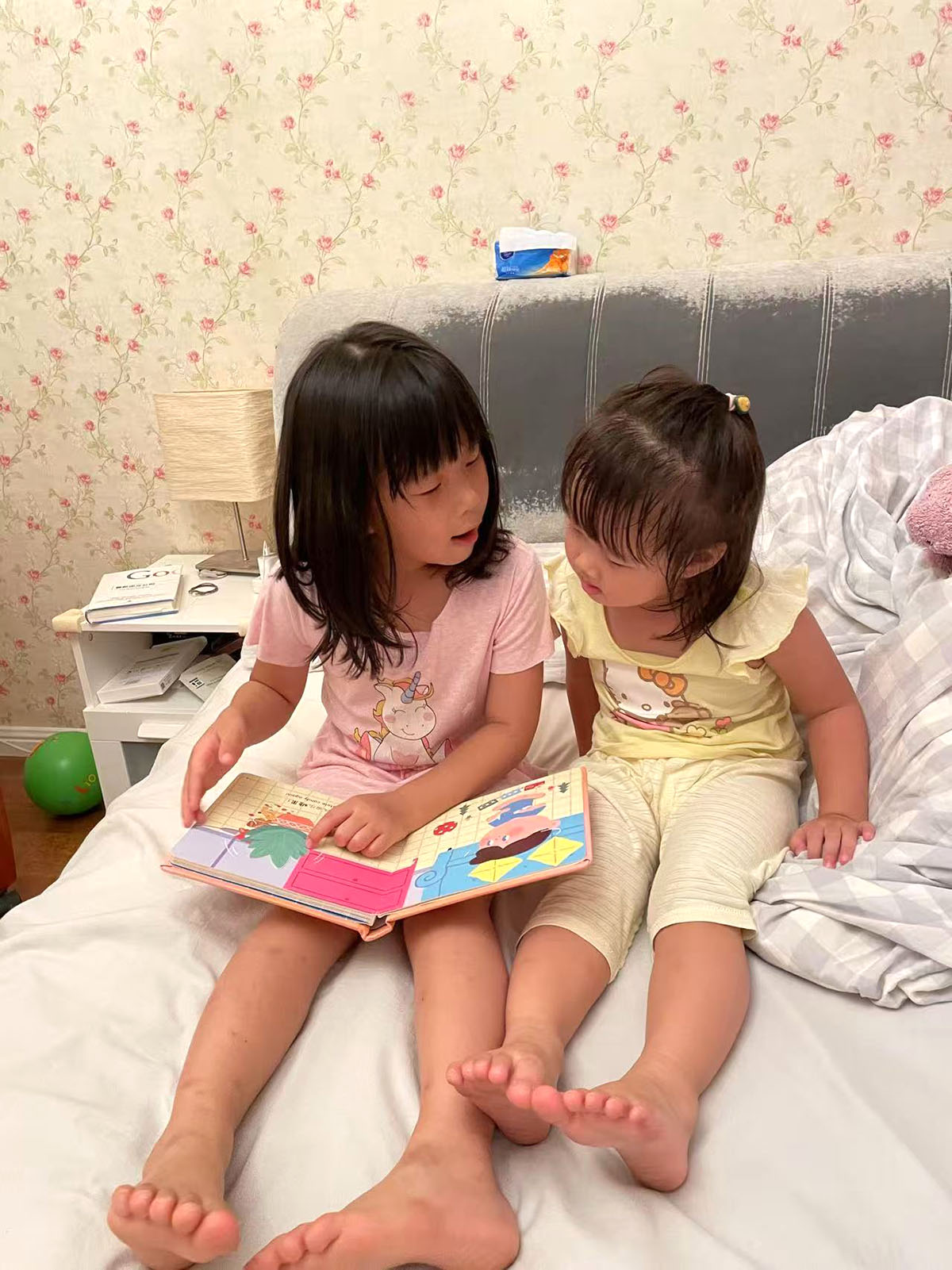

Beijing mother Shao Chenting's epiphany on changing gender roles came one evening when she was reading a bedtime story to her two daughters, ages 8 and 5.

Dressed in her pink pajamas and nestled between the two girls she opened the pages of No, David!. The main character, a 5-year-old boy, misbehaves all the time and on every page it is the mother who admonishes him. The story starts with the line: "David's mother always said — No, David!"

Shao's question was: "Where's the dad in this family?"

This moment forced her to look at the broader world of children's media her daughters were consuming.

Her older girl's favorite picture book series from Japan, Butt Detective, talks about the protagonist's father, who is also a detective and often joins him in adventures. The mother is barely mentioned.

In many other children's books Shao has bought, mothers were invariably shown wearing an apron, doing chores, and looking after the children when the fathers are absent.

She also realized the same was true for cartoons. In the Japanese anime Crayon Shin-chan, the mother is portrayed as someone who "doesn't go to work and handles all kinds of housework every day".

"Moms wearing aprons seemed normal to me," said Shao. "Maybe deep down, I still think women should take on more housework."

Even though domestic chores and parenting are supposedly more equal today, Shao said, "if it's the dad wearing an apron, I might wonder if it's a single-parent household."

She had primarily purchased foreign picture books for her children, and largely relied on recommendations from parenting groups without closely scrutinizing the content.

Domestic 'servant'

Xiao Yuman from Xi'an, Shaanxi province, has been reading both Chinese and foreign picture books to her 11-year-old daughter since the child was an infant.

She says the very name "Apron Mom" ties the character to domestic labor, reducing her identity to that of a household servant. The father's professional identity as an engineer is frequently mentioned, while the mother's occupation is rarely, if ever, addressed.

"This reinforced the traditional gender divide of men working outside and women staying inside," said Xiao.

"Apron Mom shouldered nearly all household duties, while Small-Head Dad was often absent from housework due to work commitments, which hinted at a broader societal tolerance for low paternal involvement in child rearing."

For Maebo, these strong responses toward this last-century cartoon point to wider social progress.

"It's about how women's voices are growing stronger as they become more engaged in production in society," she said.

"As a classic cartoon, the characters were familiar to almost every household, but looking at the story from Apron Mom's perspective feels like a fresh angle. It's the classic image of motherhood clashing with modern social thinking — that tension makes people pause."

Maebo said in real life she had never encountered anyone like Apron Mom "an emotionless machine that silently performs unpaid domestic labor without resistance".

Her awareness of gender roles began early in life. Her father took on more parenting responsibilities, while her mother focused on running a business.

"As a child, I often felt confused. What I saw on television didn't match what I experienced at home," she said.

Yang Yiyi, a Chinese PhD student in the United States, said straddling both Eastern and Western cultures had prompted her to reflect deeply on the gender dynamics in her family.

Her mother is from Jilin province, and her father is from Shandong province. She recalls the stark division of labor during Chinese New Year celebrations.

"The women would handle almost all the food preparation while the men sat around drinking and chatting," she said. "Even my uncle, known for being an excellent cook, still relied on the women in the family to assist him in the kitchen, while the other men remained uninvolved."

Yang said family attitudes toward childbirth also differed. She found it strange to hear men — her father and his brothers — talk so casually about how "it's good to have children and how people should have more".

"They're not the ones going through pregnancy. They don't have a uterus, yet they speak as if the physical and emotional burden on women doesn't matter," she said.

'Idealized' devotion

Xiao, from Xi'an, is concerned about the recurring portrayal of mothers as self-sacrificing figures in children's stories.

She pointed to the popular traditional tale Meng Mu San Qian (Mencius' Mother Relocates Three Times) as an example. In the story, Mencius' mother moves home to ensure a good learning environment for her son, an example of how maternal devotion is often idealized.

Xiao said such narratives risk turning mothers into "sacred instruments of sacrifice", defined by their dedication to their children.

"Mencius' mother's greatness is undeniable," Xiao said.

"But where is Mencius in the story? He comes across as a puppet shaped entirely by his environment. Shouldn't the child's choice matter too?"

Xiao also expressed concern that glorifying unconditional maternal sacrifice, without any nuance, can obscure real-life emotional complexities — and in some cases, lead to unhealthy or even tragic outcomes.

Living between two cultures, Yang believes that gender expectations around parenting are not unique to China. From conversations with peers in the US, particularly her Asian American classmates, she has found that similar dynamics persist in Western settings. Some of her American-born Chinese friends said their families still somehow manage to be "traditional".

The imbalance in how mothers and fathers are portrayed and expected to behave, whether in children's books, cartoons, or real life, is a shared cultural issue, Yang believes.

Importance of fathers

Contrary to some stereotypes, the involvement of men in child raising and home life is crucial, according to at least one expert.

Linda Nielsen is a professor of adolescent and educational psychology at Wake Forest University in North Carolina, and an expert on shared physical custody for children of divorce.

She has been working on parenting issues for decades, and challenges the widespread belief that fathers are less capable than mothers in nurturing children's social and emotional development.

"We have bought into negative stereotypes about fathers that do not reflect reality," said Nielsen. "We have embraced many demeaning, insulting beliefs about fathers that are baseless and run counter to the research and to national statistics."

Citing decades of research, she explained that children who regularly engage in active, stimulating interactions with their fathers — especially during early childhood — tend to exhibit lower levels of aggression, better emotional regulation, and more advanced social skills compared with those who have less involved fathers.

Nielsen also criticized the stereotype that men are inherently less empathetic or communicative than women.

Men are just as capable as women in demonstrating empathy, cooperation, and emotional understanding, according to research in her book Myths and Lies about Dads: How They Hurt Us All. The differences within each gender far outweigh any consistent differences between men and women.

She pointed out that children raised without fathers tend to score lower in empathy tests as adults, undermining the claim that women alone are responsible for teaching emotional intelligence.

Nielsen believes there is no empirical basis for assuming mothers are better than fathers at fostering children's interpersonal and emotional skills.

The belief that fathers are "less than" in this domain is a myth unsupported by science — and harmful to families and society.

Shared responsibility

In Shao's household, parenting is a shared responsibility. She and her husband have developed a system to rotate tasks — from bedtime routines to academic support.

Each night, she and her husband alternate between which child they tuck into bed, ensuring the children receive attention from both parents. While Shao initially managed all aspects of the children's studies, she eventually found the emotional toll was too much. She and her husband then divided the subjects between them.

"I told him, I'm tired from work too. It's not like there's only one earning money, right?" said Shao. "We both work, we're both exhausted. And this home doesn't belong to just me — it's our family's home, and both of us should contribute. It wasn't just my decision to have two kids, either."

However, Xiao, the mother from Xi'an, believes contemporary Chinese picture books and animated films are reflecting growing awareness of the need to balance parental roles and challenge traditional stereotypes.

ALSO READ: Gym life working out for more women

She pointed to the recent Ne Zha movie adaptations as a clear example. In these versions, Ne Zha's mother is portrayed as both loving and willing to let go — supporting her child while respecting his individuality. Her character strikes a balance between warmth and boundaries, offering protection without overreach. This transcends the earlier portrayals of Ne Zha's mother.

Looking ahead, she is looking forward to seeing more children's books and cartoons that are sincere, intelligent and colorful.

Shao hopes that future children's media and picture books will emphasize a more balanced relationship between both parents — whether in terms of household responsibilities, professional identities, or individual value.

Quality stories can encourage children to trust and communicate with both their mother and father when facing difficulties, she said.

"For picture books about families, ideally both mom and dad should appear in the story," said Shao. "And when it comes to expressing family emotions, no matter what, mom and dad both always love you — let children understand this through the books."