Historic industrial action at Australian port remembered amid 80th anniversary of war victory

As a child, Australian Ray Gamble would hear stories about how his father had to collect leftovers from the local butcher to feed fellow workers at the wharf.

“My dad, he used to talk about that hard time … he would get all the leftover meat for the workers to help them survive,” Gamble, 69, told China Daily.

His father, Norm “Sunshine” Gamble, then 25, and his colleagues were part of the 180 local wharf workers at Port Kembla in Wollongong of New South Wales, Australia, who refused to load a shipment of pig iron onto the steamship SS Dalfram bound for Japan on Nov 15, 1938.

The workers had heard that the iron would be utilized to produce weapons to be used against China, which was fighting Japanese invaders.

The port protest, which became known as the Dalfram Dispute, soon involved unions and other workers in the region and beyond, stretching over 10 weeks and leading to a lockout of ships, with about 4,000 steelworkers also laid off, as it garnered support from local residents and drew national and international attention.

“My father was a very staunch unionist and they were the ones who got together and stopped the pig iron being loaded,” said Ray Gamble, who also worked in maritime services and retired two years ago.

Ray Gamble, whose father died in 2002, said his children and other members of the younger generation also know very well this important time in the family’s history.

“I’ve explained to them what their grandfather and all the others went through; they’re proud of their grandfather,” he said.

The workers’ action at Port Kembla is widely lauded as a historic example of building peace and common ties across borders, with community leaders in Australia pointing to its renewed significance amid events commemorating the 80th anniversary of the victory in the Chinese People’s War of Resistance Against Japanese Aggression (1931-45) and the World Anti-Fascist War.

Garry Keane, 70, former secretary of the Southern New South Wales Branch of the Maritime Union of Australia, told China Daily in an exclusive interview that it is timely to be reminded of such an incident that occurred in this part of Australia.

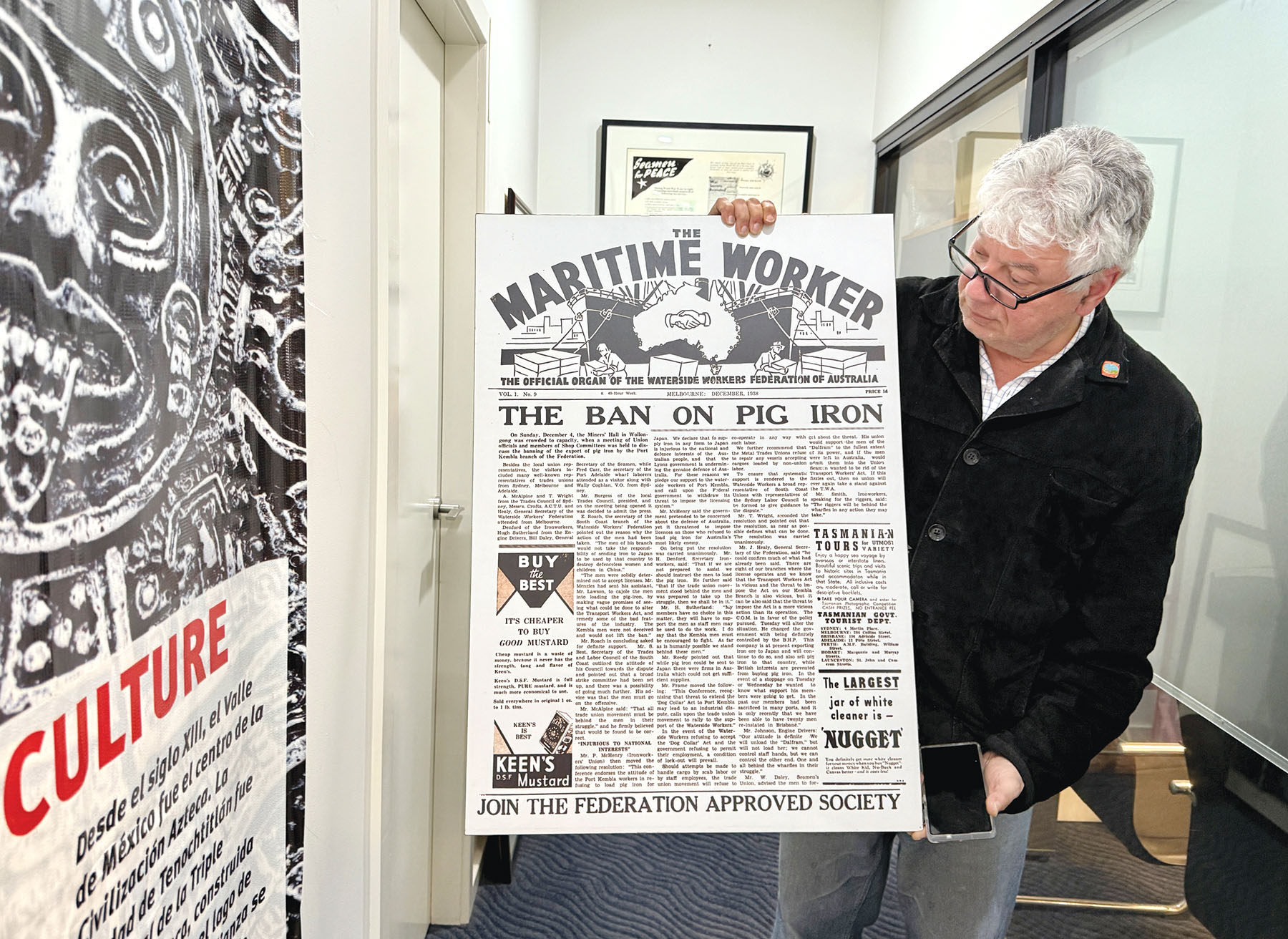

The maritime union traces its roots to the Waterside Workers’ Federation, which was behind the campaign in Wollongong opposing the Japanese invasion of China.

During the dispute, which highlighted Australian workers’ strong sense of solidarity with China and the broad anti-war sentiment, the Chinese community offered food and other support for the workers on the picket line, Keane said.

“The Chinese community in Sydney was very strong and they used to bring truckloads of vegetables from the markets down to the picket line,” said Keane, who was also deputy national presiding officer of the maritime union.

“It really did build a bond. This bond was forged during that time and it has been maintained over the past decades. We have a close association with the Chinese community,” he said, adding that the Dalfram Dispute is commemorated every year on Nov 15 at the Port Kembla Heritage Park, joined by members of the Chinese community, with similar events to remember the Nanjing Massacre.

Arthur Rorris, 57, secretary of the South Coast Labour Council, Wollongong, told China Daily that the Dalfram Dispute was important in showing how workers led with their stance for peace.

“This changed the face of Australian unionism and it changed the face as well of collective efforts with the relationships between the broader community and the union movement,” said Rorris, adding that the dispute influenced Australian foreign policy in facing increasing hostilities amid the run-up to World War II.

It wasn’t that long after World War I, when young people’s blood was spilt, Rorris said. “What had become apparent was that it’s always the workers whose blood is spilt in a time of war. And they said, ‘why should our blood be spilt for that?’ Sometimes you do have to do that to defend your country, to defend a rightful cause, but not for the interests of imperialists and others.

“That is why the workers’ action was so important and had a lasting change, because what they said is that we will have a seat on that table where you make the decisions about who is our enemy and who is not.”

Rorris added that “it was very clear that the workers … had a greater consciousness of the world and … the events unfolding in China”.

“Our workers felt a greater alignment in their interest and concern for their brothers and sisters in China than for the bosses who wanted to make a profit by sending iron to Japan,” he said, while noting that World War II Japanese attacks on Australia subsequently included the bombing of Darwin in northern Australia.

“What was done, how it was done, how it united all of the communities, the Chinese community, the broader Australian community, the workers here and abroad, these things are very significant, which is why we commemorate them,” Rorris said.

The Dalfram Dispute ended in January 1939 with the wharf workers going back to work, after union-government negotiations that encompassed future pig iron exports.

“They ended up loading the Dalfram but that finished the trade of pig iron to Japan. It was Australian foreign policy (at that time) to sell the pig iron, though knowing what was coming,” Keane said.

“But it was the action of those 180 waterside workers that actually changed the foreign policy and stopped that trade.”

Australian director Sandra Pires, who directed the 2015 documentary, The Dalfram Dispute 1938: Pig Iron Bob, told China Daily that it was “an internationally significant action … by men who believed they were going to make a difference; they had a conscience, and they won”.

“They are on the right part of history,” said Pires, whose film title refers to the nickname given to Australia’s then attorney general Robert Menzies amid his opposition to the workers’ action.

Christian Raymond, 30, told China Daily that the Dalfram Dispute is important to him as a young Australian because “it reminds us of a moment when Australians stood up to take a position in opposition to war, in support of peace across the world”.

Raymond, a public servant and member of the Communist Party of Australia, said he regularly visits the heritage park, where there is a monument attesting to “the stand against military aggression; a stand forever forged between the peoples of China and Australia”.

The significance of the Dalfram Dispute is being revisited amid the 80th anniversary of the victory in the World Anti-Fascist War, including a major symphonic concert and photo exhibition held in Sydney on Aug 9.

The “Ode to Peace and the Future” concert presented performers in a 58-piece symphony orchestra and 260-strong choir.

Speaking at the concert, Chinese Consul General in Sydney Wang Yu said that Chinese and Australians had stood united against fascism.

The Dalfram Dispute monument stands “silently recounting the heroic act of Australian workers”, he said.

“The ladder at the top of the monument symbolizes the yearning for peace and serves as a bridge connecting the friendship between the people of our two countries.”

Mark Buttigieg, New South Wales parliamentary secretary for industrial relations and multiculturalism, said that “unless we gather together and remember what happened in our past, in terms of loss of human life and wars … unless we’re vigilant, we can go down that negative path of the dark age again”.

Rorris from the South Coast Labour Council said events like the concert are always important to help remember the path to peace and progress forged eight decades ago by the port workers.

“We have a saying here that history is the workers’ greatest friend. You must never ever forget how we came to be, where we are,” he said.

“We are a relatively affluent country, we still have our issues but all of the protections and the benefits and our standard of living were won through the march of the labor movement. They were achieved by the working class,” Rorris said.

The seafarers in Australia played a major role in highlighting the sacrifices made by the Chinese people during the war, he said.

“The very nature of their work meant that they saw firsthand what was happening in many of these other countries because they would go to the ports. So a lot of the information that came back to their unions was firsthand information,” Rorris said.

During and after the war, it became a lot clearer the sacrifices that had been made, he said.

“People are starting to realize more and more how the resistance in China was a turning point … At the end of the day, the history of Chinese struggle is critical here.”

“There were great sacrifices that should never have happened. But it also means that in (regard to Australia), there’s no doubt the Dalfram Dispute was the first shot fired in the war against fascism in this country,” Rorris said.

Once again across the oceans, we can extend that friendship with the Chinese people and people around the world, he said, adding: “And to say that we must plan for peace, not war and not fall into the trap of thinking that we can arm ourselves to peace.”

“When you look at Dalfram … the people always have a say, the people will get out and their voice will be heard,” Keane said.

“There’s a saying among our movement, that peace is union business and the unions will always be involved in peace, not war.”

Contact the reporters at xinxin@chinadaily.com.cn