Ancient artisans who worked meticulously for merchant patrons are nameless today

Editor’s note: Traditional arts and crafts are supreme examples of Chinese cultural heritage. China Daily is publishing this series to show how master artisans are using dedication and innovation to inject new life into heritage. In this installment, we explore wood, stone and brick carving in architecture in the Huizhou area.

For Kuai Zhenghua, a 62-year-old national-level intangible cultural heritage inheritor of Huizhou wood carving based in Huangshan, Anhui province, restoring ancient wood carvings is initially a game of detective work, and requires experience, intuition, and imagination.

For example, when restoring one piece on which there were traces of elephant farming, he knew it depicted the story of the legendary ruler Shun, who is believed to have lived over 4,000 years ago.

“It’s a famous story about the cultural importance of filial piety. I have seen so many carvings about it and can recognize it at a glance. In the story, Shun’s display of filial obedience touched heaven and led to elephants farming for him,” said Kuai.

“The legendary ruler Yao, who is said to be the predecessor of Shun, heard the story and visited Shun to ascertain whether his character qualified him to take over his throne, before passing the mantle of leadership to Shun,” Kuai continued.

“Although there are often many missing parts, clues remain. For example, even if the heads of some figures are gone, you can still see their feet and clothing. Men often have bigger feet than women. Farmers don’t wear long robes, but officials do. Women’s costumes often have ribbons. Since these carvings usually depict legends, with clues like these, you can figure out which stories they are about,” Kuai added.

Once he understands a carving’s content, he can restore it. The pieces he has worked on over the last four decades once decorated the buildings of Huizhou, a historical prefecture, which straddled the border between southern Anhui and northern Jiangxi provinces and covered the area of modern-day Huangshan.

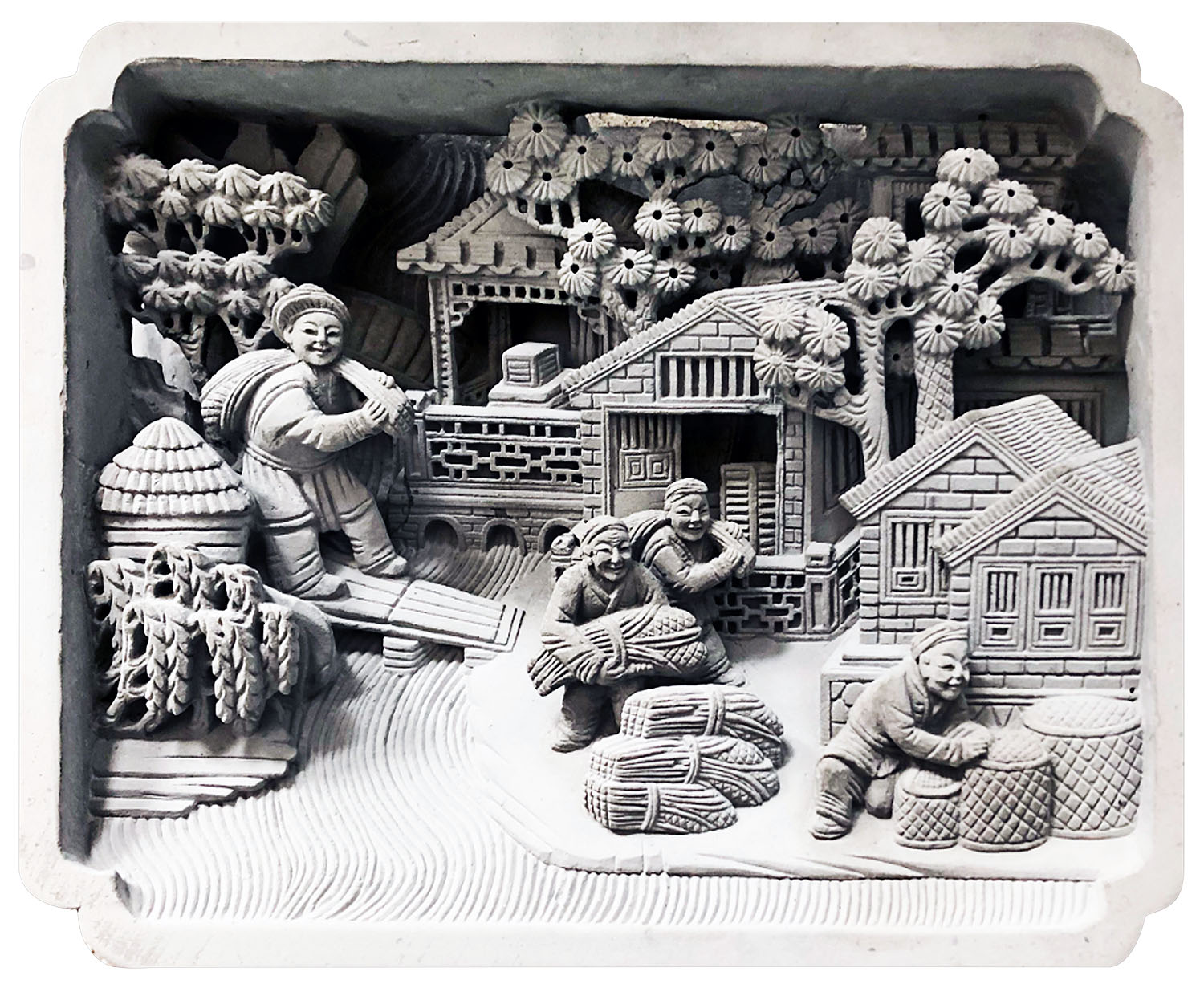

Stone, brick, and wood carvings — collectively known as the “three carvings” in Huizhou — have been integral components of Huizhou’s architecture since the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644).

Different types of carving work in coordination and are used in specific parts of buildings, giving rise to the exquisite decor for which Huizhou architecture is known, said Chen Zheng, deputy secretary-general of the Huangshan Intangible Cultural Heritage Research Association.

Historical buildings are often found nestled in mountainous areas. Residential buildings, one of the most important typologies, are enclosed by walls and look simple from the outside, but inside, they are open, spacious, and intricately decorated.

Chen said the popularity of the “three carvings” is closely related to the rise of Huizhou’s merchants, a class reputed for their honesty and morality during the Ming and Qing (1644-1911) dynasties.

Since Huizhou is a mountainous area with few flat areas for farming, its people often left the region at a young age to do business. Once they were successful and wanted to build homes for their twilight years, lack of land meant they could not build bigger buildings, so instead, they resorted to luxurious decoration to display their hard-earned prosperity.

Wood carving is widely believed to be the most important among the “three carvings”.

“People often say, ‘even if the walls collapse, Huizhou houses will not’, because their wooden structures use sunmao (mortise-and-tenon) joints. That’s why for interior decoration, the wooden beams and window lattices are the primary choices, and that’s where wood carving comes into play,” said Chen.

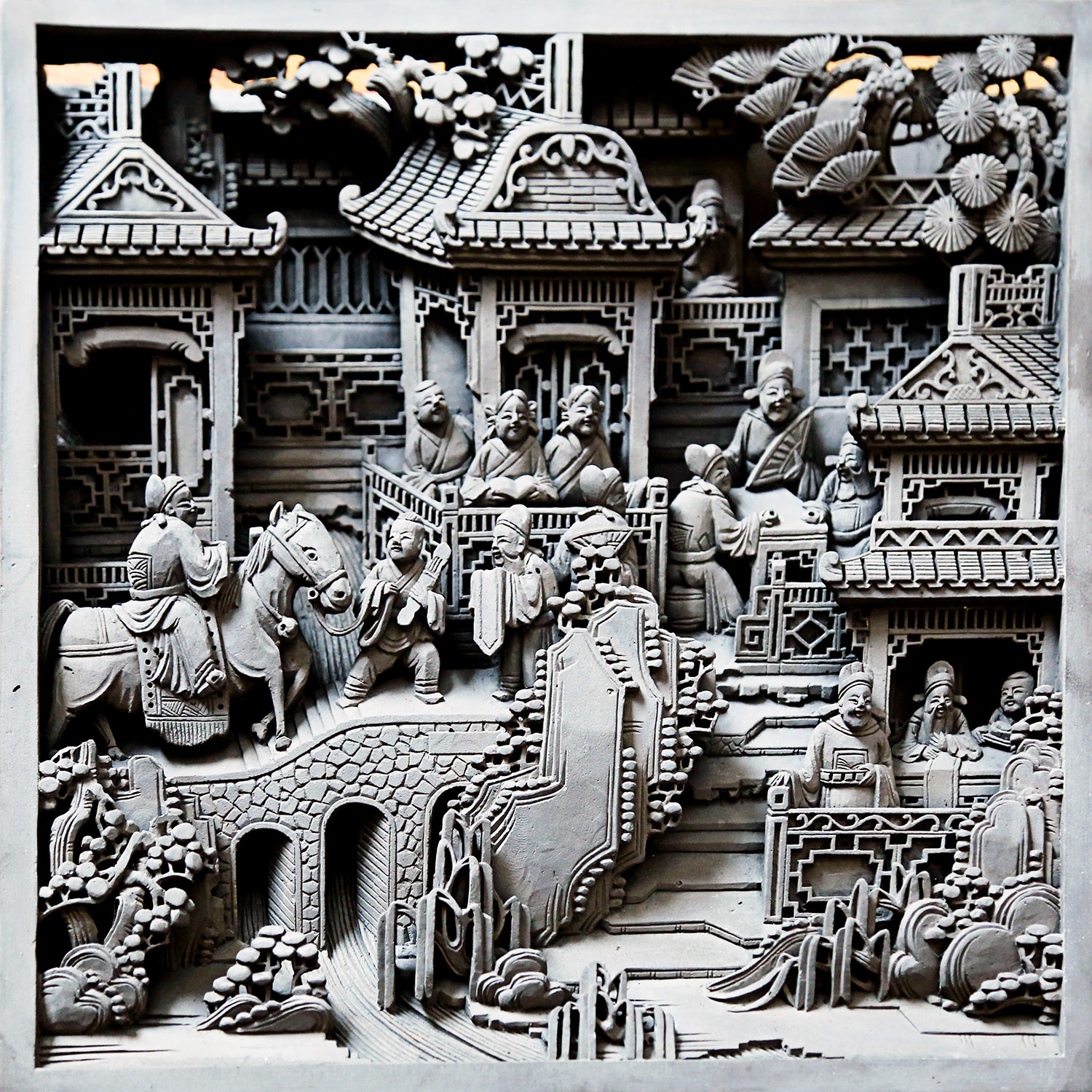

He further explained that brick carvings typically adorn the entrances of ancient residences to signify the owners’ status, but stone carvings are commonly found on pillar bases and are more prevalent in ancestral temples and on paifang, or memorial arches.

Chengzhi Hall in Huangshan’s Yixian county is a classic example of Huizhou architecture. The former residence of Qing Dynasty salt merchant Wang Dinggui is known for its outstanding wood carvings. Visitors often remark that their eyes can barely take in all the beautiful examples around the complex.

One beam in the main hall is decorated with a carving depicting a Tang Dynasty (618-907) prince’s party attended by many officials. The carving is intricate, and all the figures are painstakingly carved, including the servant in the right corner brewing tea, and another in the left corner cleaning the ears of an official.

Huang Jie, vice-president of the Yixian Huihuang Tourism Development Group, which is responsible for promoting scenic spots in the area, said the carving symbolizes the owner’s wish to become an official.

She explained that the carvings embody Wang’s aspirations. Beyond conveying his ambition to attain an official position, they also symbolize his drive for prosperity in business, his wishes for the longevity of elderly relatives, and his desire for the flourishing of his descendants.

“In the past, people could grasp the homeowner’s mindset by examining these carvings, as they encapsulated the owner’s aspirations and wishes. Consequently, buildings served not only as residential spaces but also as spiritual sanctuaries for their inhabitants,” she added.

Chen said the stone carvings at the Wu family’s ancestral temple in Shexian county depict 10 famous views of Hangzhou’s West Lake in Zhejiang province.

Legend has it that a family member who grew prosperous doing business in Hangzhou sought to fulfill his elderly mother’s desire to witness his success, and recruited skilled artisans to replicate Hangzhou’s scenic beauty on the blue-stone boards of their ancestral temple, thus allowing his mother to experience the city’s splendor without undertaking a tiring journey.

“This embodies filial piety and devotion to family bonds through an enduring display of love and respect,” he said. The exquisite carvings were the work of Huizhou craftsmen, a group known during the Ming and Qing dynasties for their skill in various art forms including carving and woodblock printing.

Their success was tied to the support of Huizhou merchants, who devoted a great deal of wealth to the best materials. Artisans were given plenty of time to build the splendid homes where the merchants sought to retire. As a result, craftspeople had both the money and the time to work meticulously, and satisfy their patrons, Chen said.

He makes particular mention of the wood carvings in a residence in Yixian county’s Lucun village, which are said to have been worked on by two artisans for nearly 20 years, a demonstration of the determination and devotion of Huizhou merchants to have the perfect dwelling, no matter the cost.

Huizhou’s craftspeople were highly skilled, but apart from being known for their accomplishment, most failed to leave their names in history. Their legacy, however, continues to shine.

“The artisans behind the ‘three carvings’ are nameless today. They were known only during their times and didn’t enjoy high social status, but it was precisely these ordinary people who made such breathtaking work,” said Chen.

According to Kuai, Huizhou wood carving emphasizes simplicity. Its smooth, simple lines and intricate yet modest carving techniques render beauty in an elegant and poetic way, in harmony with the cultural atmosphere of the area.

He said that since wood is softer than brick and stone, and is easier to carve, it can be more richly detailed and express a more delicate sentiment than the latter.

According to tradition, when carving a representation of a 3-year-old child, the eyes should dominate nearly half of the face, while the jawline should be rounded. For a depiction of a 10-year-old, the eyes should be positioned higher on the face, occupying a smaller area. When portraying adults, the eyes should occupy a smaller proportion of the face, often set in a more angular facial structure.

“From 3-year-olds to adults, the carving of different age groups varies based on observations of the maturing process. This is the basic principle of our wood carving tradition,” said Kuai.

According to Wu Zhenghui, a 58-year-old national-level intangible cultural heritage inheritor of Huizhou brick carving, the tradition is known for its multiple layers, which can result in an almost three-dimensional effect that makes them look more dynamic.

“By making recourse to multilayered carving, Huizhou brick carving transcends flat, two-dimensional presentation, and introduces techniques of perspective that advance toward three-dimensional art,” said Wu.

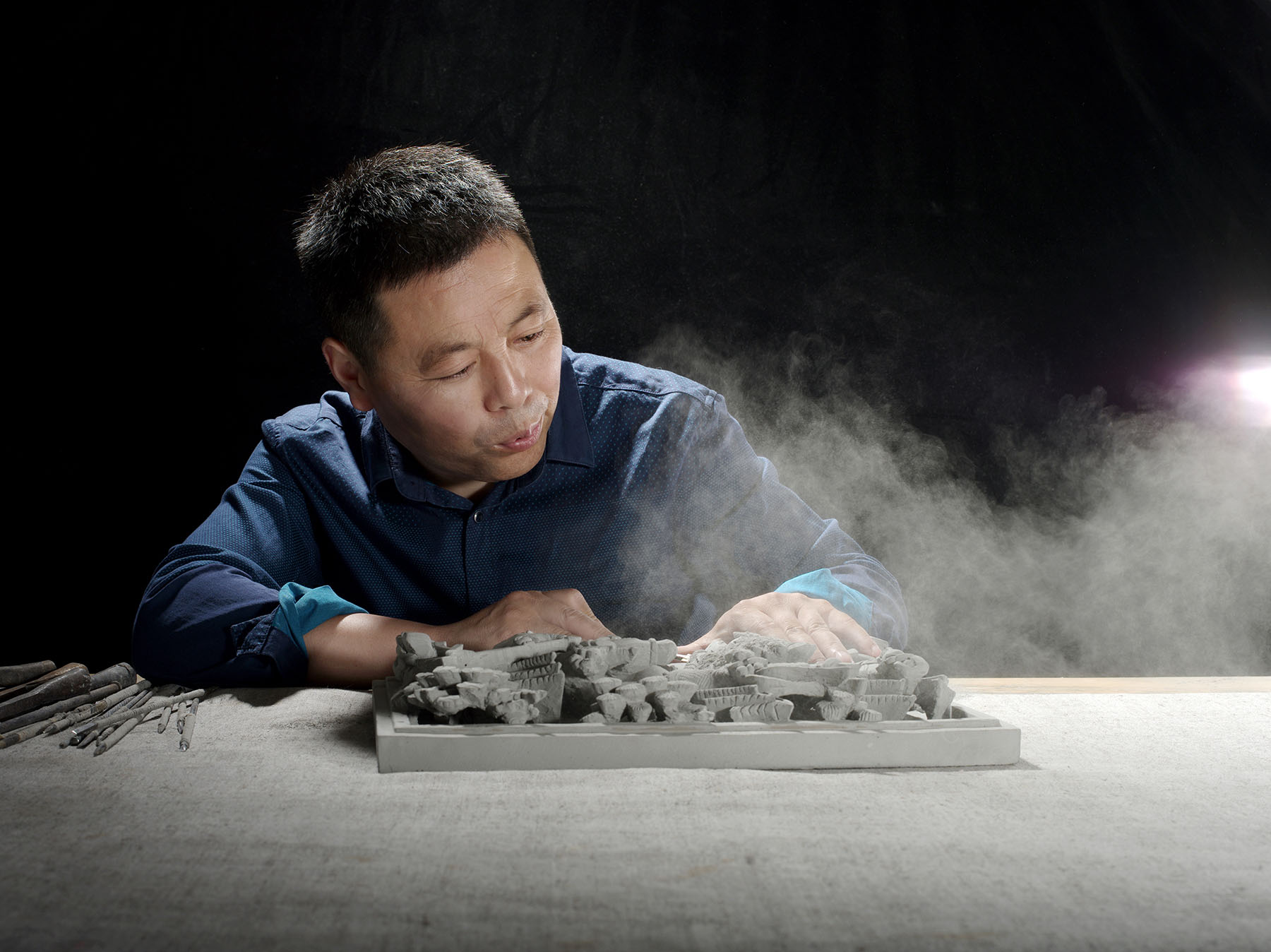

A native of Shexian’s Bei’an village, the birthplace of Huizhou brick carving, Wu was immersed in the art form from a young age, fostering a passion for this time-honored craft since childhood. He learned from local artisans before opening his own studio to restore old brick carvings in 1989.

Years of involvement in the craft and continual improvement have made Wu a leading figure in the field. He demonstrated his skill by spending six months re-creating the ancient technique of nine-layered carvings, which had been lost to history.

“Working from the front, you can carve at most seven layers before being unable to go any deeper. As a result, I was confused as to how I could add the other two layers,” said Wu.

He read widely and examined carvings on historical buildings, thinking about how to add those two extra layers.

One day, as he was looking at some old brick carvings he collected, he noticed openings on the sides of the bricks. At first he thought they were to help install the carvings, but after close observation, he realized he could insert a knife through these openings and carve two more layers. This was how he was able to re-create the technique successfully.

One of Kuai’s students is 29-year-old Tang Shuhui, a city-level inheritor of Huizhou wood carving who has been engaged in the craft for 11 years.

From a young apprentice whose hands hurt every day from sharpening knives to a mature craftsman with many award-winning pieces, Tang wants to continue following the path walked by his predecessors.

He said that people often compare Huizhou merchants to camels, noting their pioneering, enterprising spirit, and endurance. He believes this comparison can be applied to Huizhou craftspeople, too.

“I want to learn the skills and spirit they passed down, advance the techniques with modern tools, and try my best to add new vigor to this traditional craft,” he said.

Contact the writers at wangru1@chinadaily.com.cn