Ancient bamboo and wooden texts reveal a sophisticated system of governance, Fang Aiqing reports.

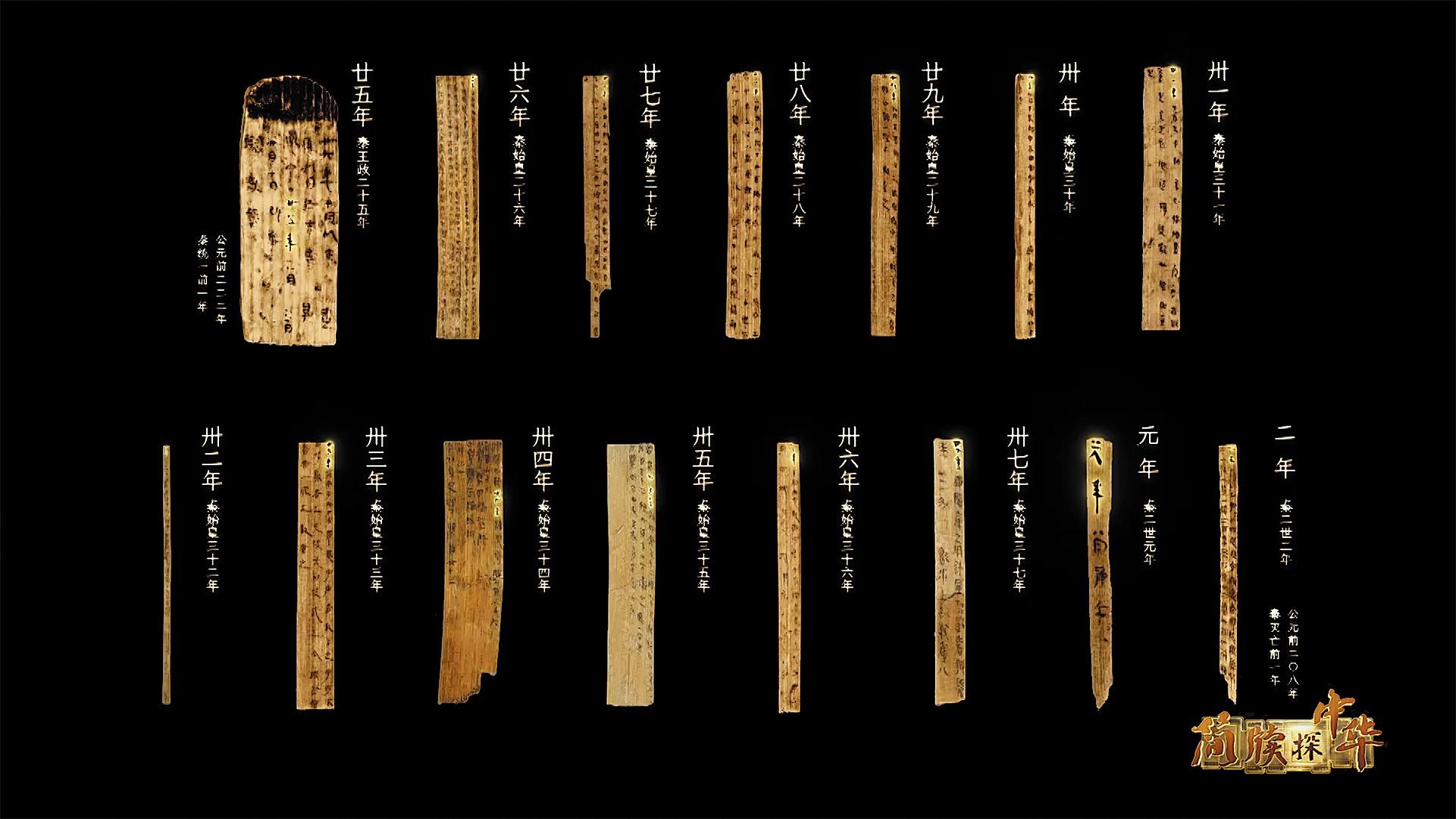

Qin Dynasty (221-206 BC) bamboo and wooden slips unearthed from the ancient town of Liye, Hunan province. (PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Qin Dynasty (221-206 BC) bamboo and wooden slips unearthed from the ancient town of Liye, Hunan province. (PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Western Han Dynasty (206 BC-AD 24) historian Sima Qian once lamented there were few historical records about the Qin Dynasty (221-206 BC). "What a pity! There's only Qinji (Records of Qin), but it doesn't give the dates, and the text is not specific," he wrote, when compiling a chapter on chronology for his Shiji (Records of the Grand Historian).

If an ancient master felt frustrated, you can well imagine how present-day scholars feel. But sometimes a breakthrough happens.

The Liye slips help us piece together what it was like in Qianling. We can therefore speculate how the government worked in the more than 1,100 counties of that time and how people lived.

Zhang Chunlong, paleographer

Sima would have been incredibly envious if he were told that more than 38,000 pieces of bamboo and wooden slips were kept in an old well in the ancient town of Liye, Central China's Hunan province, and would be unearthed more than 2,000 years after his time.

The figure is 10 times the total amount of Qin Dynasty slips discovered before. These documents are a comprehensive record of the administration, defense, economy and social life of a county, Qianling, from 222 BC, the year before Qin annexed the other six states of the Warring States Period (475-221 BC) and founded the dynasty, to 208 BC, not long before Qin's downfall.

"For the first time, documents left by Qin officials prove the existence of a county," says Zhang Chunlong, researcher at the Hunan Provincial Institute of Cultural Relics and Archaeology, in the first episode of cultural variety show Jiandu Tan Zhonghua (Discovering China in the Bamboo and Wooden Slips), broadcast on China Central Television's channel, CCTV-1, since Nov 25.

Zhang joined the excavation of the 16-meter-deep ancient well in 2002, describing the delicate slips, when discovered, as like "overcooked noodles". The archaeologists had to hold them, from the earth, very carefully in both hands so as not to destroy them.

"The Liye slips help us piece together what it was like in Qianling. We can therefore speculate how the government worked in the more than 1,100 counties of that time and how people lived. The slips made this part of history come alive," Zhang says.

The first two episodes of the show, featuring the Liye slips, have performers act out stories the relics tell. (PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

The first two episodes of the show, featuring the Liye slips, have performers act out stories the relics tell. (PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

He adds that archaeologists discovered 13 more ancient wells at Liye in spring. The bamboo and wooden pieces brought up from these wells suggest more slips are likely to be excavated.

The variety show, with scenes of several cultural relic sites around the country where slips have been unearthed, and interviews with archaeologists and historians, tells the stories of the relics, their isolation and rediscovery, as well as updated research findings, says Ma Hongtao, one of the chief directors.

So far, more than 300,000 pieces of bamboo and wooden slips have been excavated across China. Slips were common before paper was invented. They were widely used for more than 1,500 years.

According to Wang Zijin, a renowned expert on the history of Qin and Han (206 BC-AD 220) dynasties, the slips are mainly ancient classics, government documents and folk documents like personal letters, all crucial materials for a glimpse of the past.

A poster for the show. (PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

A poster for the show. (PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Some of the ancient books were scattered or lost, some were different from the documents handed down through history. Notably, the folk documents have numerous, trivial remarks of grassroots life that were unseen in official history records, Wang says.

The 73-year-old historian is one of the guests of the show.

The first two episodes, featuring the Liye slips, pictured an ancient downtown with a prosperous marketplace. The region abounded with orange groves. Residents made wine from grains they grew. Local wax gourds and dried fish were presented to the emperor as tributes. Raw lacquer was used to decorate armor and shields.

Back then, people applied the multiplication table for calculation. They used simple fractions, too. The piece of slip inscribed with the table confirms that Chinese people started using the method more than 600 years earlier than the West.

Some of the slips listed the area of land reclaimed and the land rent, while some, functioning like today's passports, detailed personal information, especially descriptions on an individual's appearance.

Paleographer Zhang Chunlong, who joined the excavation of the Liye slips in 2002.(PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Paleographer Zhang Chunlong, who joined the excavation of the Liye slips in 2002.(PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

The slips evidenced that the Qin Dynasty had developed an efficient postal system that facilitated its direct administration over localities. One such slip tracked the distance between different administrative units.

Archaeologists have also discovered what can be seen as the earliest envelope, marked with a postal priority.

According to Zhang and Wang, Qin officials needed to have written documents for every item of work — verbal requests didn't count — and each should be noted with the date and operators who handled the task, and how the work and goods were handed over.

"In fact, life of the Qin residents was not all that removed from us," Ma, the director, says.

To make it fun and easier to understand, the production team strung together the information on the slips, created storylines — while major events conform to the historical facts, some plots were fictional — and performers acted them out.

From the first two episodes, the audiences see how Qin officials were dispatched to take over a land that used to belong to the Chu state, how they governed, how the two cultures blended and the people got along.

Historian Wang Zijin attend the cultural variety show, Jiandu Tan Zhonghua (Discovering China in the Bamboo and Wooden Slips), broadcast on CCTV-1. (PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Historian Wang Zijin attend the cultural variety show, Jiandu Tan Zhonghua (Discovering China in the Bamboo and Wooden Slips), broadcast on CCTV-1. (PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

It was common then that government sectors were short-handed and had to transfer staff elsewhere.

The Qin Dynasty was known for its strict laws and regulations. When higher officials came to assess the performance of local officials, tough questions were asked, and Chang, the last governor of Qianling, became awkward and anxious, as is shown in the performance.

Audiences can also see in the performance how Hua, a Chu local, volunteered to explain the law to the people in case they broke it out of ignorance. Hua later became the secretary of government. Throughout the period these Liye slips covered, he carved down what we can read from them today.

Ma says, the production team has been working on the 11-episode variety show since November 2022.

"By creating a dialogue across time and space, we want to stress the importance of the Chinese contextual inheritance," he says.

According to him, later episodes of the show will involve slips found at a Qin tomb in Shuihudi village, Yunmeng county of Hubei province, a Han tomb at the Yinque Mountain of Shandong province, the sites of Xuanquanzhi and Yumen Pass of Gansu province, and more.

Contact the writer at fangaiqing@chinadaily.com.cn