As a major exhibition, featuring more than 200 works by iconic Japanese artist Yayoi Kusama opens at M+, Chitralekha Basu turns to its curators and Kusama experts for some gloss on the show.

At M+'s ongoing exhibition, Yayoi Kusama: 1945 to Now, a visitor takes in some of the artist's most recent, playfully effervescent works. (CALVIN NG / CHINA DAILY)

At M+'s ongoing exhibition, Yayoi Kusama: 1945 to Now, a visitor takes in some of the artist's most recent, playfully effervescent works. (CALVIN NG / CHINA DAILY)

I

Doryun Chong, deputy director, curatorial and chief curator, M+, co-curator, Yayoi Kusama: 1945 to Now

Would you like to tell us a bit about the newly commissioned site-specific works and how they complement and/or highlight M+’s unique architectural features?

We have installed three of these. And each responds in its own way to M+’s unique architectural features.

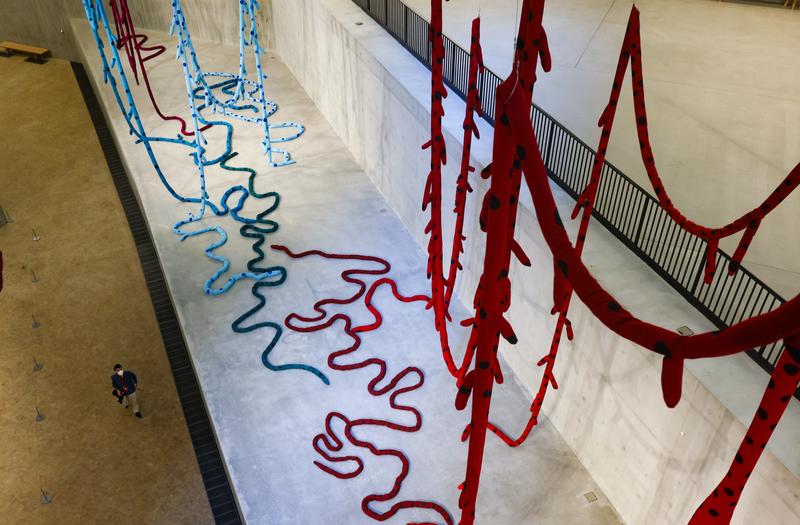

There is Death of Nerves (2022), an M+ commission. It hangs from the ceiling of the ground floor, draping down to the next three levels. It’s in the space we call the Lightwell, a vertical soaring space. The piece was designed with that particular architecture in mind and is open to public view.

Dots Obsession – Aspiring to Heaven’s Love ( 2022) is installed in our studio. It’s a bunker-like space with a 9-meter-high ceiling inside the basement. Inside it there’s a partial mirror room framing a smaller one. Kusama has produced infinity mirror rooms and inflatable sculpture spaces before but here she’s combining them together. So she’s definitely responding to that particular space.

Pumpkin (2022) comprises two large-scale public sculptures, hot off the factory. They are in our ground floor level space.

Is there a particular ethos or vibe these new works are expected to represent?

What we’re trying to accomplish in this exhibition is to highlight the depth, breadth and complexity of her practice.

It’s indisputable that she’s one of the most well-known and respected living artists of our time. She’s a global cultural icon. Even people who don’t follow contemporary art would know about this quirky Japanese artist in a red wig and polka-dot dress. What this exhibition is trying to do is to show unknown sides of her working practice in a career spanning seven decades.

The new works are (only) one of the portals of understanding seven decades of her career. Kusama certainly doesn’t need to prove anything. Having said that, I feel we’re creating an opportunity for even fans of her work to understand how multi-layered her practice is.

These new works go back to earlier examples. For instance, Death of Nerves is based on a piece she made in 1976, also included in our exhibition. She has gone back to a work that’s 44 years old and reinterpreted it.

In that sense, we’re showing the continuity of her practice. Also how her old practice remains a constant source of inspiration.

How did it all come together for such a large-scale exhibition, featuring over 200 of Kusama’s works?

I feel it all could come together only through a miracle. We began work on the project in 2018. The curatorial process was started in 2019, which was not an easy year for Hong Kong. And then the pandemic happened, which meant seeing the artist and her studio, traveling to see potential lenders and the works, and discuss loans… all of those things had to happen digitally and remotely.

The forced isolation was an opportunity to reflect on how we do our job. There were certain things that were indeed lost. If you cannot see a piece of art in the flesh, you cannot fully grasp their impact.

There is an expert and dedicated team working in Kusama’s studio. They serve as her eyes and ears and we collaborated closely with them. Mika (Yoshitake, Chong’s co-curator) is based in the US, and hence was able to visit some of the American lenders. We tried to make the best of the situation.

Leaving aside the challenges of logistics and practicality, we went through a pandemic—an epidemiological crisis. There was also such an emotional and psychological impact on the global populace that everybody is now openly and honestly talking about mental health issues.

This is something Kusama has been doing for decades. It was an incredibly brave thing to do, especially for someone coming from an Asian culture and a woman, to be so open and candid about her struggles. The mental health issues she had in many ways were so prophetic and prescient about where our culture would be at this moment. She’s always believed in and has been very vocal about the therapeutic power of art, its power to heal, and I think that’s ever more relevant at this moment. So as I see it, this pandemic-induced strictures and struggles actually gave us a new framework to understand Kusama’s art and also art in general.

A section of the Death of Nerves (2022), a site-specific installation cutting across three floors of the M+ building. (CALVIN NG / CHINA DAILY)

A section of the Death of Nerves (2022), a site-specific installation cutting across three floors of the M+ building. (CALVIN NG / CHINA DAILY)

Seeing that Yayoi Kusama: 1945 to Now comes with a pricey ticket (HK$240), would you like to tell us about the public programs around the show, especially those that can be enjoyed free of cost?

Our learning team has designed a number of workshops for different age levels. There are family focused activities inspired by Kusama: her idea of infinity, for instance (Family Day Art Workshop: Kusama’s Cosmic Portrait). Our cinema program around the Kusama exhibition will launch in January, with the screening of a 2018 documentary on Kusama’s life and art, Kusama: Infinity by Heather Lenz.

We try to contextualize (the art we showcase). For instance, who were the other women/feminist artists in 1960s New York when Kusama lived there? There is an upcoming program around that.

After she came back to Tokyo in 1973, what was the atmosphere there like for a woman artist? There are related screening programs.

The pricey ticket is all very relative.

We’ve attracted more than 2 million visitors so far and about a quarter of them are return visitors. So there are hundreds of thousands of visitors out there who have gotten used to coming to M+ again and again.

Many Hong Kong people have adopted M+ as their hometown museum. I don’t think ticket price is such a barrier.

Going from a free-to-visit museum to a paid museum (M+ scrapped free general admissions from November 12) is a huge transition and we are very mindful of creating free content available to the public.

What is Yayoi Kusama: 1945 to Now expected to achieve on behalf of Hong Kong, its community and its art ecosystem?

There is no doubt that Kusama is one of the most inspiring figures in art and culture of our time. In Hong Kong, every single auction in the past five years had a piece by Kusama, often a pumpkin sculpture or drawing.

What this exhibition will do is to establish her status not only as an artist but also a visionary thinker who thought up the idea of universal connectivity in an infinite network. Before the invention of social media, she saw prophetically that these things were coming.

So we have an opportunity to understand the depth, breadth and radical nature of her philosophy. It is an enriching experience for all artists and the art ecosystem.

What M+ will deliver for Hong Kong’s professional arts community is a global level international standard museum show marked by diversity of content. We opened the museum with more than 1500 artworks by more than 700 artists and makers from around the world. That set a firm foundation for looking at global visual culture through Hong Kong perspective. Our Kusama show, centring on an artist who is internationally known, and shown at some of the most major prestigious cultural institutions around the world, lands on that particular foundation: what does global visual culture look like from the cosmopolitan viewpoint of Hong Kong? I think that’s a very productive (endeavor) and should give our art community something to think about.

Would you say our experience of the world and the time we are living in is incomplete by not knowing the works of Kusama?

The pandemic-induced struggles and situations that we went through… that was something Kusama had been speaking about and even embodied for decades. And that is about the power of art to heal and keep you going. (Since the pandemic began) this has been really palpable — something you could experience.

I have been thinking much more deeply about her writing, statements and her art in the process of curating her works for the exhibition, (categorizing them under) the ideas of infinity, infinite connection, self-obliteration and radical connectivity. It made me realize that she had thought about humanity and its relation with nature and the universe in a deep way for such a long time and had predicted where humanity was going to be.

I think through her art you gain a new understanding of life and without that understanding life indeed is incomplete.

Mika Yoshitake and Doryun Chong, co-curators of Yayoi Kusama: 1945 to Now. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY BY M+, HONG KONG)

Mika Yoshitake and Doryun Chong, co-curators of Yayoi Kusama: 1945 to Now. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY BY M+, HONG KONG)

II

Mika Yoshitake, co-curator, Yayoi Kusama: 1945 to Now

What would you say is the surprise element in Yayoi Kusama: 1945 to Now, given a sizeable section of M+’s visitors (from Hong Kong and elsewhere) are already more-than-familiar with the artist’s works through auctions, art gallery exhibitions and fairly recent retrospective shows in Washington DC, Tokyo, New York and Tel Aviv?

This is my third Kusama exhibition as a curator (following Yayoi Kusama: Infinity Mirrors, in 2017, at the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden in Washington DC, and KUSAMA: Cosmic Nature at New York Botanical Garden in 2021).

I think the key factor is that we are presenting her work in a way that frames some of the motifs and ideas that cut through critical moments of her career — converging in those moments while also spanning across time. There are new themes that have not been addressed in previous exhibitions which have been, mostly, chronological.

Through my research for the two earlier exhibitions I came up with the bio-cosmic theme, which integrates the earthly and the cosmic nature of her practice and that’s something that has never been addressed before.

We are also looking at her philosophy, called self-obliteration, which is this idea of inter-connectivity among mankind. It cuts through the 60s to her most recent works. So we are looking at specific lenses that cohesively narrate her work. Even if some of the paintings, sculptures and installations have been presented before, here you see them in a very different kind of refreshing light.

It’s not about just the polka dots, pumpkins and mirrors that the public tends to focus on in a very superficial way.

How would you say Kusama has resolved the dichotomy between making pop/consumer-pleasing art and touching the heights of artistic achievement?

I don’t think she herself views it as a dichotomy. She’s not strategically being avant-garde and popular at the same time. I think it’s all the same for her. She calls herself an avant-garde artist. Even when it comes to her most popular works which do get over-exposed through social media and merchandizing, I think, from the artist’s point of view, it’s a form of memory for the public to relate to. The merchandize is a part of her trying to disseminate her own vision of connecting with people through her art. Whether it be through the merchandize or the million-dollar paintings, it’s on the same level for her. Her collaborations (with product designers) are highly selective.

Do curators such as yourself see a conflict between Kusama the artist and Kusama replicating or adapting her own works for mass consumption or do they believe these two aspects can happily coexist in Kusama’s life and career?

Kusama had her own line of clothing, Kusama Enterprises, since the 1960s. The tunics (costumes bearing Kusama’s infinity net pattern and trademark soft protrusions) on display are part of her radical period when she was organizing the Happenings series of performances in 1968-69. Later on she designed clothes with holes for the genitals. I think she was always trying to be ahead of her time and there was a socio-political aspect to those costumes as well.

In the Radical Connectivity section, you see this in the archival photographs and slide shows of performances. The videos of performances from the 1980s were never shown before. Kusama collaborated with filmmakers. It’s all a part of her. Her practice is about conception and production and this becomes a part of her oeuvre, as seen throughout the exhibition.

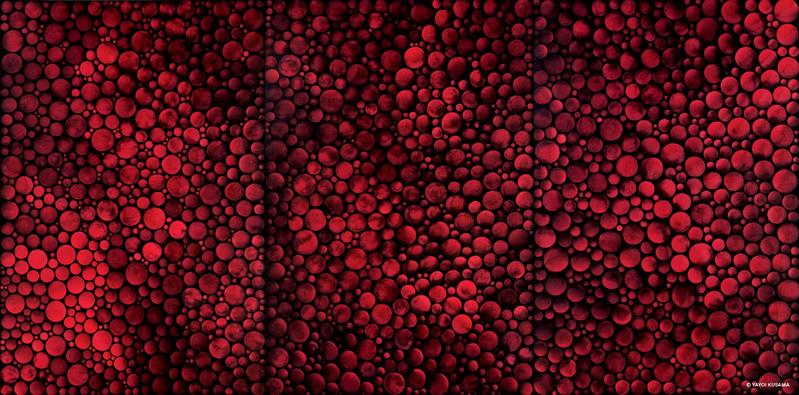

An Yayoi Kusama triptych, Accumulation of Stardust, (2001). (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY BY M+, HONG KONG)

An Yayoi Kusama triptych, Accumulation of Stardust, (2001). (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY BY M+, HONG KONG)

Would you like to tell us about the significance of Kusama’s generic emblems such as dots, mirrors and pumpkins and if you see a progression in the ways they have been used in her works since the 1960s?

Absolutely. She grew up in a seed nursery her family owned. Our show tracks the historic progression of her relationship with Japan. During World War II, she worked as a seamstress in parachute factories.

Her first experience of pumpkins was of her grandfather walking her through a field. She had a very visceral reaction to the pumpkin and the bio-cosmic section of the exhibition addresses this very grotesque but also adoring relationship she has with nature.

One of her earliest pumpkin sketches, drawn when she was growing up in Kyoto, is now lost. She began drawing pumpkins over and over again in a way that the image became almost like an abstraction. There’s a meditative quality to it.

You see that evolution — the pumpkin becoming an abstraction — through the (introduction of the) polka dots and different (repetitive) patterns.

We have two major big sculptural works, Pumpkin, (2022) reflecting a grotesque, biomorphic element in objects that are perfect and round (in real life).

These forms stand the test of time because they are universal. People from all walks of life relate to them. The polka dot is a highly abstract form but also highly symbolic, like the sun and moon. She started drawing polka dots in the 1950s. They are also related to the hallucinations she was having.

The (ideas of) connection, similarity and repetition are symbolic of a community. One dot suggests isolation. Two suggest connection and dialogue. Three suggest community. It’s a kind of world building for her.

There is also the idea of negative space about polka dots, that of infinity.

We focus on her interest in organic forms… the moments of ephemerality or serendipity. For instance, in 1957, on her way to New York, she was flying over the Pacific Ocean. Looking down at ocean currents, she began to imagine the abstract forms of ocean currents as nets. The idea appears throughout the Infinity section of the exhibition, covering the period from the 1950s to the present.

The idea of infinity is a recurring form in her works but I would say there is a progress. For instance, in Transmigration, 2011, an infinity net painting across four panels, there’s a very toxic, green neon quality to it. It’s produced in the same year as the Fukushima nuclear disaster and the (Tohoku earthquake and) tsunami. It was her response to what was happening in the world.

Would you say our experience of the world and the time we live in is incomplete by not knowing the works of Kusama?

One of the important themes arising out of this exhibition is the notion of healing. She offers visually, through her latest paintings, a model of how to survive. She went through a deep depression about survival in the 1960s and ‘70s, especially after her return to Japan. And that story is not very well known. Her productivity decreased after 1973. That’s when she began writing novels. It’s absolutely amazing… a resurrection of sorts. We’re showing the diversity of the works that she made in her deepest, darkest periods.

Those are the moments I would have missed if I lived a life without knowing the works of Kusama. They anticipate us trying to deal with our shared isolation during the pandemic. It’s amazing how this 93-year-old artist who has been working for seven decades can now offer a kind of life lesson. She’s come out of this crazy period of isolation and is still painting every day. I think her life is about the beauty of survival.

Seeing that Kusama has been ever the avant-garde, one wonders what she makes of the new technologies embraced by artists around the world.

She’s been approached by VR and NFT companies, but she’s still painting, working in the traditional medium. She understands the times, but her art is not reflective of those technologies. She’s filtering her experience of the world into more conventional practices.

Lately, she’s started writing a lot of poems on the back of her paintings which is new. She’s a prolific writer, having received literary awards in the 1970s and ‘80s. We have translated quite a bit of her writing, poetry and parts of her novels for the show’s 400-page catalog.

Midori Yamamura, academic and author of Yayoi Kusama: Inventing the Singular. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Midori Yamamura, academic and author of Yayoi Kusama: Inventing the Singular. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

III

Midori Yamamura, associate professor of art history, Dept of Art, The City University of New York, Kingsborough; author, Yayoi Kusama: Inventing the Singular

Does Yayoi Kusama: 1945 to Now look any different from the Kusama retrospective shows you have seen before?

Kusama often speaks about art as a healing process. She has anxiety neurosis and copes with her neurological disorder by engaging in artistic creation. I think it is a special experience to see Kusama’s oeuvre at this particular moment when we are just about coming out of more than two and half years of pandemic. Also, held in Hong Kong, the exhibition features many artworks on loan from collections all over Asia, which will be interesting for people who have not visited Kusama retrospectives in other Asian cities, such as Singapore and Japan.

Would you say between them the thematic categories — Self Portrait, Infinity, Accumulation, Bio-cosmic, Death, Force of Life — cover all aspects of Kusama’s oeuvre?

I believe there are many more ways to look at and understand Kusama. However, I do think the show’s six themes cover major characteristics of her art. Among them, bio-cosmic is a new concept which people started seeing in Kusama’s works at the 2021 New York Botanical Garden exhibition where one of the co-curators of the M+ exhibition, Mika Yoshitake, was a guest curator.

Kusama grew up in a family that owns a plant nursery. She has a close relation to plants and flowers. In this age of environmental crisis, the way she sees and connects with the natural world and expresses that connection visually is very timely and important. The infinite expansion of the cosmic world in her works signals that humans cannot live alone and that we are all part of the immense universe, connected to one another through fragile relationships. I believe the bio-cosmic theme is an important aspect of her work, illuminated nicely in this exhibition.

Would you have a comment on the site-specific new commission, Death of Nerves, a technicolor, magnified version of its 1976 prototype, and some of the other public art on show as part of the M+ exhibition?

I saw an iteration of Death of Nerves, called Black Nerves, at Kusama’s Robert Miller Gallery show in New York in 2006, so no surprises there.

Among the public art commissions, I believe the images of Kusama pumpkins on the walls of MTR trains running on the Tuen Ma Line work well. It is new. In Kusama’s hometown, Matsumoto City, they have polka-dotted buses. But I haven’t seen images adapted from Kusama’s works on the walls of public transportation outside of Matsumoto before.

In the mid-1960s, Kusama began displaying her artworks in public spaces. The best-known artwork from this period is Narcissus Garden (1500 mirror orbs laid out on the ground) which she showed at the 1966 Venice Biennale. Through the outdoor site-specific installations, she wanted to make her art available to people from all walks of life.

The art train is a fantastic idea. Kusama must be very happy about it.

The M+ show does not shy away from showing Kusama at her most bold, racy, in-your-face avatar. Photographs from the Happenings series of performances from the ‘60s — marked by nudity and suggestive gestures — are presented in the form of a slide show, for instance. What would you say is the value of what used to be radical and shocking in the ‘60s in today’s world?

Kusama was familiar with psychotropic drugs through treatment of her anxiety neurosis. In the latter half of the 1960s, she was into creating psychedelic spectacles. In New York, marijuana will be legalized this winter. Scientists are making a case for the health benefits of marijuana —which is ironic when seen in the light of the ban on psychotropic drugs since 1965. I believe the 1960s psychedelic culture that encouraged the youth to drop out of the tribal game and look for happiness outside of accumulating material wealth remains valid in today’s neoliberal world.

A section of the Yayoi Kusama: 1945 to Now exhibition at M+, showing (left) Kusama's floral paintings (1979); (middle) Self-Obliteration (1966-74) and (right) soft sculptures resembling biomorphic forms. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY BY M+, HONG KONG)

A section of the Yayoi Kusama: 1945 to Now exhibition at M+, showing (left) Kusama's floral paintings (1979); (middle) Self-Obliteration (1966-74) and (right) soft sculptures resembling biomorphic forms. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY BY M+, HONG KONG)

There’s also the curious mix of creepily grotesque and endearing, a muppet-like quality, if you like, about Kusama’s works, as in sofa sets growing multiple hands, or a giant red flower-shaped soft sculpture reclining like a benign crocodile. Would you like to comment?

In one of Kusama’s novellas, she describes how she created special paint to create both soft and eerie effects in her soft-sculptures. So, if you find them creepily grotesque and endearing, it means her calculated technique worked out.

Would you say Kusama’s over-exposure — through social media and merchandizing (M+ has developed a whole new range of products around the show) — could come in the way of her being taken seriously?

She emerged out of the pop art circle. They tried to make art accessible to people from all walks of life. For example, at the 1966 Venice Biennale, she sold her mirrored orbs for $2, competing with Andy Warhol who sold his small flower prints for $5 a piece at the Leo Castelli Gallery in 1965.

The range of products developed around the show is an important part of art history. I believe people should take it very seriously.

I am particularly interested in the Kusama tattoo design workshop hosted by M+ as part of its public program. This is something new, and yet reminds people of an important, yet overlooked aspect of Kusama’s art. In 1969, Kusama ran two body painting studios in New York. It is interesting to see how body painting is materialized in this exhibition.

The exhibition begins with abstract self-portraits, imagined like a malignant, carnivorous flower (1950) with claw-like petals and concludes with a whole wall full of images (acrylic and marker pen on canvas) Kusama painted in the summer of 2022… a series of joyous, life-affirming paintings in fluorescent colors. Most of these new works have the same title: Every Day I Pray for Love. Would you like to comment on Kusama’s trajectory as an artist and her place in the contemporary art world?

At Kusama’s first US retrospective in 1989, art critic Kim Levin had called her the “Odd Woman Out” in Village Voice. At that time it was difficult to put Kusama into an existing category, especially since the world of art was centered on white male artists. The artist’s self-proclaimed episodes of mental illness promoted since 1975 further isolated her from the established art history. Kusama’s Tate Modern exhibition in 2012 was the first historical re-contextualization of her art detached from her neurological disorder, establishing the important place she occupied in art history, particularly the 1960s New York art scene.

Also, the 1960s commercial art market typically excluded women artists. Kusama thus needed to archive her own achievements. The boxes she sent back from New York to Japan contained countless articles on her art, her notes on them and her art campaigns, as well as her appointment book with the details. Her early malignant carnivorous flower-like portrait may have been a projection of her uncertain future as a woman artist.

Her happier-looking self-portraits emerged for the first time in the sculptures included in Hi, Konnichiwa (Hello)!, a large-scale installation shown at Mori Art Museum in 2004. I believe her life-affirming portraits came into being once she had earned her due recognition in the art world.

She always has a good grasp of the time she is living in and captures it in her art. In many ways, especially when you look at the ongoing disinformation wars, we have a situation similar to the time when fascism emerged in the 1930s. So Kusama’s prayer for love, and peace, in her latest series of paintings might be seen as an extension of the 1960s Flower Power slogan, “Make Love, Not War”, a sincere aspiration for a peaceful future, coming from a person who has lived through the Pacific and Vietnam wars.

Jacky Ho, Head of Evening Sale, 20th and 21st Century Art Department, Christie's Asia Pacific. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Jacky Ho, Head of Evening Sale, 20th and 21st Century Art Department, Christie's Asia Pacific. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

IV

Jacky Ho, Head of Evening Sale, 20th and 21st Century Art Department, Christie’s Asia Pacific

Yayoi Kusama’s works have been part of every Hong Kong sale/auction of contemporary art in the last five years. As an auction house insider dealing with the artist’s works on a regular basis, were there any surprises for you at M+’s Yayoi Kusama: 1945 to Now exhibition?

As auctioneers we connect the suppliers to the market. Whereas we tend to focus more on where a particular piece sits in an artist’s career in terms of period, size, quality and rarity, the M+ exhibition offers a birds’ eye view of Kusama’s creations and her career.

I think the M+ show offers a fresh Asian perspective in a way that’s very non-judgmental. It’s very different from other Kusama shows where they are often focusing on her New York or Japanese periods. I think it’s a well-balanced display, thematically arranged, rather than following a chronological order. I feel I need to go back several times to study this thematic arrangement more closely.

Would you say Kusama’s over-exposure — through social media and merchandizing and M+ is into it as well, having developed a whole new range of products around the show — could come in the way of her being taken seriously as the visionary artist that she’s being pitched as?

Nowadays people do not draw a line between an artist’s commercial success and greatness. Just because you’re popular doesn’t mean you can’t be a serious(ly talented) artist. That dividing line disappeared 20 years ago. And Kusama is one of the pioneers who helped achieve that.

Do you see her popularity in the secondary market rising after the M+ experience?

The show only opened last week, so there is a great deal of anticipation, but it will take at least two months to gauge if there’s any impact on the secondary market.

In the past year Kusama’s auction records were broken twice: in Hong Kong (in Dec 2021 at a Christie’s Evening Sale, when a pumpkin painting fetched over $8 million) and in New York, when Untitled (Nets) sold at a Phillips auction in May for $10.5 million.

So regardless of what the M+ exhibition achieves on Kusama’s behalf, her stocks are on the rise.

What for you is the standout feature of the show in terms of curators’ vision?

It’s a really well-researched exhibition for which I assume the curators looked at everything that’s been done before to come up with a new angle. It’s not easy to bring (together works representing) someone so famous and diverse, and whose works span 70 plus years. It must be quite a challenge deciding what to include.

I think it was clever to go about it thematically and under each of those themes the display was chronological. For example, the exhibition begins with some of Kusama’s earliest available self-portraits (1950-53) as well as one of her latest (2020). I think the show gives a clear picture (of Kusama’s oeuvre) to those who are new to it and at the same time it is refreshing for Kusama experts.

If you are asked to choose one particular image or installation from the show, what would it be?

I would pick the works covering 70 years of self-portraits displayed on a single wall. I felt that ensemble of self-portraits is very powerful and striking.

What is your take on the site-specific installations?

Death of Nerves is more accessible, because it’s displayed across three floors. As for Dots Obsession, the infinity mirror room in the basement, I’d recommend that’s where viewers start their journey, rather than the main exhibition hall. It’s a practical piece of advice if you want to avoid the queues.

How could a show like this benefit Hong Kong’s art ecosystem, including auction houses such as the one you represent?

I think in a mature market we have the auction houses, art galleries and museums. They all have their distinctive functions. Among these, auction houses are concerned with the commercial side (of art), galleries nurture artists’ careers while museums can look at artists’ works objectively, in an academic way, with a focus on art history.

I don’t think before the M+ show, Hong Kong has seen an exhibition of Kusama’s works where the curation is world-class. I think it has put Hong Kong on a new level where we’re not just commercially successful, in terms of auctions but also academically on solid ground. The show has great educational value for the local community. While previously I would be blown away by exhibitions in London and New York museums, now I can have a similar experience in my hometown.

The M+ show has educational value for people in the art circuit as well as those starting their art journey.

But we’ve had a taste of high standards of curation since M+ opened a year ago. Is there anything particularly about the Kusama show that’s great for Hong Kong’s art scene?

I think the Kusama show is really special because it’s not limited to the M+ collection. They decided on a theme which materialized through sourcing artworks on loan. This exhibition demonstrates what M+ is capable of in terms of presenting a chapter of art history.

What is your takeaway from the Kusama show at M+?

My takeaway is that I need to go back to the exhibition several times. And this is speaking as a Kusama fanatic. Even the works I’ve seen before, elsewhere, are presented in this exhibition with a new X factor.

And I can actually do the revisits over the next six months because the show is in my hometown.

Was there anything you missed in the show though?

I think the one thing that is missing is Kusama herself. Kusama’s performances are an important part of her art. I think it would have been perfect if she could be present at the opening and sing for us. I have seen her perform before. Given it’s such a major retrospective of her works it would have been an amazing experience to see her come out and perform.