Dedicated conservators piece together the past in Hong Kong

Lesley Liu Yuyang (center), head of the University of Hong Kong's Libraries Preservation Centre and Conservation Laboratory, introduces the collections of Luo Zhenfu, an imperial physician in the late Qing Dynasty, to students at the university in November. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Lesley Liu Yuyang (center), head of the University of Hong Kong's Libraries Preservation Centre and Conservation Laboratory, introduces the collections of Luo Zhenfu, an imperial physician in the late Qing Dynasty, to students at the university in November. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

For the past few years, Silas Lee Choi-leung, a 67-year-old retiree in Hong Kong, spent every Wednesday restoring ancient books at a museum in the city, rather than joining his friends for morning tea.

His restoration work was voluntary, and Lee was seldom late or absent.

At 10 am on Wednesdays from 2016 to 2019, he arrived at the Hong Kong Museum of History in Tsim Sha Tsui and headed to the restoration laboratory. Rows of brushes hung from a wall, reference books and bottles of chemicals packed the shelves, and paper scrolls filled a corner of the room.

Lee donned a lab coat, placed tweezers, scissors and an art knife on his work desk, and began his weekly practice of repairing book pages that had yellowed.

He stayed until 5 pm-sometimes 6 pm-and returned the following week to continue any unfinished work. From 2016 to 2019, he helped restore more than 500 paper items.

"To do this work, you must be patient, and you cannot rush. It tests you," Lee said.

From being a layman who simply followed the instructions of professional conservators, Lee gained experience year by year, and learned to repair different types of paper items on his own.

Viewing each restoration project as a "fantastic journey", he traveled between several dynasties when restoring the Twenty-Four Histories, official records covering the earliest dynasty in 3000 BC to the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644).

Lee also discovered the beauty of clothes made from paper when handling a book about the Ghost Festival, and he also dealt with posters about life in Hong Kong when it was invaded by the Japanese.

Under his care, stacks of paper items that were torn, holed or which had mold, were cleaned, reassembled and preserved. "After this work, these items look fresh to the reader, and are strong enough to withstand future tests of time," he said.

Lee took part in the volunteer program operated by the Leisure and Cultural Services Department, or LCSD, until the plan was suspended in 2019 due to social unrest in Hong Kong and the COVID-19 pandemic.

His work reflected the city's growing interest in and attention paid to conserving cultural relics.

To preserve the 1 million-plus relics in the city, professional conservators and enthusiastic culture lovers using eastern and western techniques continue to hone their skills amid unprecedented challenges.

Their work has become an indispensable part of Hong Kong's ambitious goal to become a hub for arts and cultural exchanges between China and rest of the world.

Martina Ho Yee-man checks the condition of a silk painting in her office at the Hong Kong Museum of Art. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Martina Ho Yee-man checks the condition of a silk painting in her office at the Hong Kong Museum of Art. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Numerous repairs

Jonathan Tse Chi-yuen began his career as a government conservator of cultural relics from museums in 1997, when Hong Kong returned to the motherland. At that time, most people were unaware of such work, he said.

Tse, now a 3D objects curator at the LCSD's Conservation Office, has repaired countless artifacts over the years, ranging from coins to a 20-meter-long railway coach and a fireboat weighing 500 metric tons that helped many stricken vessels.

In 2002, he was told his services might be needed to repair a boat, but Tse was somewhat confused, as the government's collection of relics did not include any boats.

He was assigned to work on the Alexander Grantham, Asia's largest and most advanced fireboat at that time. Built in Hong Kong in 1953, the vessel was 38.9 meters long and 15 meters high. Most of its metal components were damaged and rust had formed in numerous areas of the boat, which was taken out of service in 2002.

Never having worked on a boat, it took Tse and his colleagues nine months to repair the vessel. With the help of dockyard workers, they stripped the paint and rust on its metal parts, cleaned away salt, and carried out repainting work.

Tse, who often handled artifacts in the restoration lab, never imagined he would work on a boat. Arriving at the shipyard almost every day, he examined nearly all areas of the vessel-squatting in the cabin to remove rust, standing beneath the boat to repair the propeller, and even climbing meters-high scaffold to paint the craft.

After the restoration work, a crane was brought in from Guangzhou, capital of Guangdong province, to hoist and then lower the fireboat at Quarry Bay Park, where it was later transformed into an exhibition gallery, which has showcased Hong Kong's marine rescue history to the public since 2007.

Silas Lee Choi-leung (right) repairs the page of a book at the Hong Kong Museum of History. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Silas Lee Choi-leung (right) repairs the page of a book at the Hong Kong Museum of History. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Relentless efforts

In addition to museums operated by the LCSD, many cultural relics are owned by academic institutions, social organizations and individuals.

Every day, boxes of damaged books are delivered by a library van from the University of Hong Kong to the 14th floor of a harborside building in Aberdeen, where the University of Hong Kong Libraries Preservation Centre and Conservation Laboratory is located.

Lesley Liu Yuyang, head of the center, said this pioneering conservation facility, which focuses on books and other paper-based items, not only works on the university's collections, but also offers services to a wide range of clients in the community. On average, the team handles about 5,000 items annually.

Relentless and painstaking efforts are required for restoration work. For example, it took a conservator up to an hour to remove tape from a piece of paper, without damaging the paper itself.

The University of Hong Kong Libraries boasts a vast, unique collection of works in Chinese and English related to China and Asia, which is rare to see around the world, and is of vital importance for overseas communities to study China, Liu added.

The collection of photojournalist Frank Fischbeck, which focuses on Asian society seen through the eyes of a foreigner, is among the projects that Liu's team is working on. Fischbeck has recorded and collected a number of photographic documents about life in Hong Kong from the 1860s to the 2000s, as well as the lives of mainland people at the dawn of the People's Republic of China.

The team is also working on the collections of Luo Zhenfu, an imperial physician in the late Qing Dynasty, who moved to Hong Kong in the 1930s. The collections include Chinese medicine prescriptions, rare books and manuscripts, and correspondence with friends such as Liang Qichao, a prominent reformist at that time.

Luo specialized in treating lung diseases. His descendants donated his collections to the University of Hong Kong Libraries in 2003 during the outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome, or SARS, and again in 2020, when COVID-19 emerged.

Liu said the donors, who had been shocked by cases of pneumonia during both outbreaks, hoped Luo's collections could be well preserved to benefit future generations.

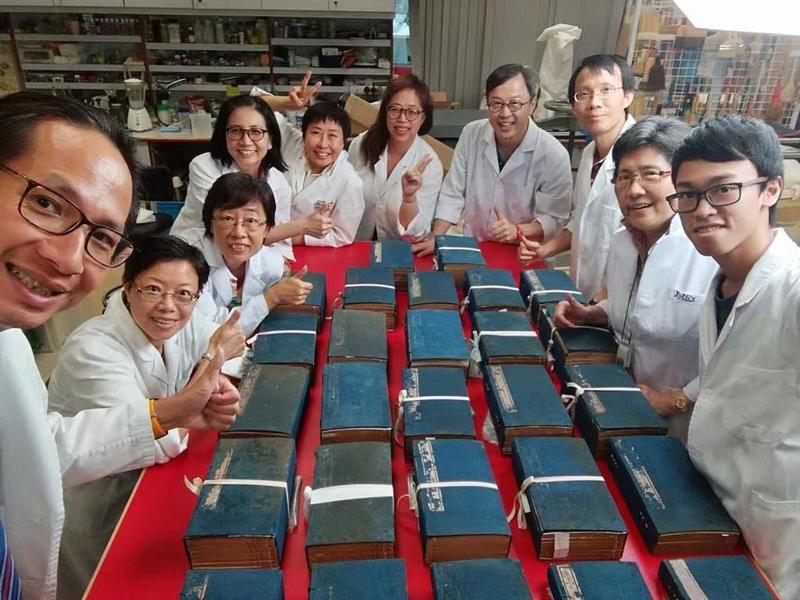

Silas Lee Choi-leung (fourth right) and other cultural relics restoration volunteers pose with books they are working on at the Hong Kong Museum of History in 2017. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Silas Lee Choi-leung (fourth right) and other cultural relics restoration volunteers pose with books they are working on at the Hong Kong Museum of History in 2017. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Top advice

As well as restoring local antiques, Hong Kong conservators learn such techniques from the nation's top professionals at the Palace Museum.

Martina Ho Yee-man, an assistant curator at the LCSD's Conservation Office, who is in her 30s, was the office's first conservator to get the chance to attend an exchange program at the Palace Museum in Beijing.

Ho attended the national museum for four months in 2015 to learn traditional Chinese methods to restore paintings. It was a totally new experience for Ho, who majored in materials science and engineering at college, and learned Western restoration methods at the LCSD.

She witnessed time-honored and exquisite craftsmanship from the masters. The first stage of learning centered on the preparation of Chinese-style restoration tools. Ho familiarized herself with needle corns, learned to sharpen a horse-hoof knife on a grindstone, and wrapped a bunch of palm fibers into brushes.

Until she could use these tools skilfully, she practiced on paintings that were not part of collections-learning step by step about cleaning, repairing and mounting. During her time at the museum, she took part in the complete restoration of a historical silk wall painting, under the guidance of teachers.

After returning home, Ho applied the skills she learned in Beijing to her daily work at the Hong Kong Museum of Art. As part of a cooperation memorandum, the LCSD conducted two further exchange programs with the Palace Museum, covering repairs to ancient buildings and scientific research of artifacts.

The painting Ode to the Goddess of the Luo River is one of 10 ancient paintings and works of calligraphy on display this month at the Hong Kong Palace Museum. (WANG SHEN / XINHUA)

The painting Ode to the Goddess of the Luo River is one of 10 ancient paintings and works of calligraphy on display this month at the Hong Kong Palace Museum. (WANG SHEN / XINHUA)

Drawn to city

Conservators worldwide have been attracted to Hong Kong to develop businesses.

Dawne Steele Pullman, a veteran self-employed painting conservator who has traveled to Hong Kong for the past 13 years, has based her business locally due to the city's huge art market and the increasing need for art conservators. She now spends most of her time in Hong Kong.

Few individuals work in private conservation practice in the city, with most of its larger art collections managed by public organizations.

As interest in all types of art continues to grow in Hong Kong, the city is making its mark globally with the establishment of the M+ art museum in the West Kowloon Cultural District. However, Pullman said there is room for more conservators in the private sector, especially for objects, paper items and textiles.

Liang Jiafang, a collection restoration director at the Hong Kong Palace Museum, who used to teach courses related to cultural relics at the University of Hong Kong, said that previously, the attention paid by the city to art and cultural collections mainly focused on their trade value. Now, the value of these treasures is being extended to areas such as education and cultural presentation.

More courses focusing on scientifically researching cultural relics-and the use of virtual technologies to present such items-have been introduced in colleges. For example, the Hong Kong Palace Museum's newly launched weekly painting restoration workshops are proving popular, Liang said.

Numerous initiatives have been launched by the Hong Kong government to support the conservation of relics.

For the 2022-23 budget, the government has allocated HK$37 million ($5.3 million) for conservators at the LCSD and the Hong Kong Palace Museum to receive training, and for local museums to expand internship programs during the next six years. Later this year, the government will seek funding from the legislature to build a designated cultural relics restoration center in Tin Shui Wai. It is planned to complete the center in four years.

Liang said that in the past, cultural relics conservation was rarely in the spotlight in Hong Kong, compared with some mainland and overseas cities similarly steeped in rich culture and history.

She added that the recent changes have been uplifting, but more important, this momentum needs to be maintained and sustainably developed.