TOKYO – Shukatsu, or end-of-life planning, is often associated with tasks that are seen as being for the elderly, such as arranging for belongings to be taken care of after one dies. Recently, however, it has grown more common among younger people, who see it from a fresh perspective: as a way of reexamining the present moment.

Two years ago, Mutsumi Suzuki, 34, an office worker from Nagareyama, Chiba prefecture, became a member of Enjoy Life Care in the city, a civil organization that supports end-of-life planning for younger generations.

“Since starting end-of-life planning, I’ve had more opportunities to reexamine my present self,” Suzuki said.

Roughly once a month, the group organizes sessions where members discuss how they want to approach their future lives, referencing their self-created informal living wills. Most of the members are women in their 30s and 40s who are raising children.

Suzuki previously worked for an insurance-related company, making preparing for the unexpected a familiar concept in her professional life.

She happened to come across the organization’s social media account and decided to join. At the time, however, she did not have a very positive image of shukatsu, which she strongly associated with death.

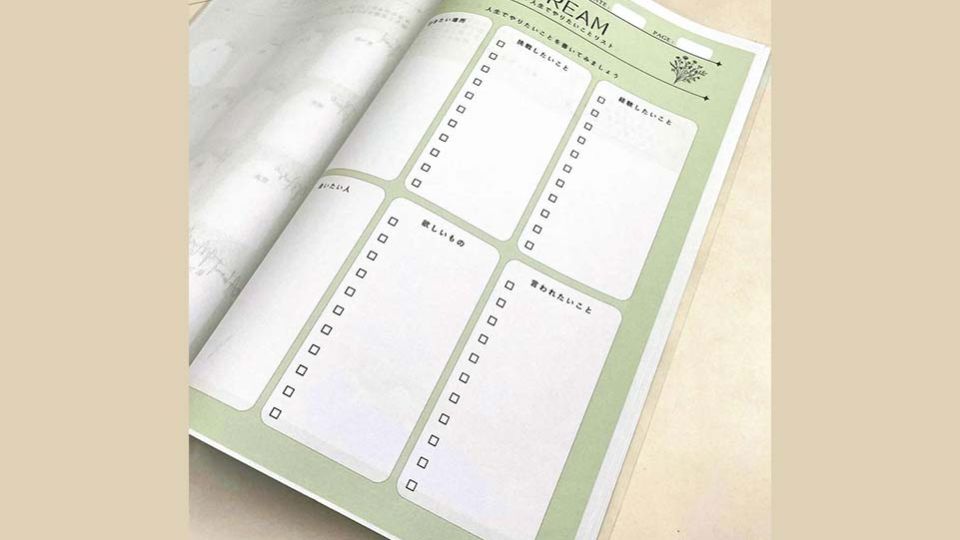

She was amazed by the items listed in the organization’s original informal living will format booklet. These items included: “Challenges I want to take on,” “Places I want to visit,” “People I want to meet” and “Things I want.”

The booklet not only focused on personal wishes regarding medical care, funeral arrangements and asset status — typical concerns for the elderly in shukatsu — but also contained many entries about “my present self.”

As Suzuki filled out the booklet during the activities, she realized, “I should think about things counting backward from the end of my life and do what I truly want.”

Following this realization, she changed jobs at the end of last year and began working in a field in which she had long been interested. “This helped me organize my thoughts. It motivated me to think about how I want to live,” she said.

In March of last year, Rakuten Insight Inc, a Tokyo-based internet research company, released the results of a survey on shukatsu targeting 1,000 men and women nationwide, aged 20 to 69. About 70 percent of respondents reported intending to engage in the practice.

The breakdown by age group was as follows: about 40 percent of men in their 20s and 60 percent of men in their 30s said they intended to do shukatsu, as did 50 percent of women in their 20s and 70 percent of women in their 30s.

Aya Seike, a social medicine specialist at Ritsumeikan University’s College of Sport and Health Science, suggests that the spread of shukatsu among younger generations may be influenced by the coronavirus pandemic. She explains that younger people have become more aware than before that death can be sudden, citing the sudden deaths of famous entertainers who contracted COVID-19.

In June, Seike conducted an experiential lecture related to shukatsu for the first time, centered on the question, “What is a better life?” Students were invited to lie down in a coffin as part of the session. She reported receiving many positive comments from the students, such as, “It gave me a chance to reexamine my way of life,” and “I realized that I still have things I want to do while I’m alive.”

“People’s perceptions of shukatsu vary by generation, and it shouldn’t be forced on them. It should be pursued in a way and at a time that suits each individual,” she said.