Hong Kong resistance fighters joined CPC-led guerrillas to liberate city from Japanese invaders

The agonized cry, “If I die, avenge me!” has echoed in Lam Chun’s mind for 82 years.

It was May 1943 in Kowloon City, when Japanese soldiers dragged her 23-year-old sister, Lam Chin, into their home. The accusation was theft — a charge fabricated after she rejected a soldier’s advances.

A laundry worker at the Japanese barracks, Lam Chin was subjected to relentless beating, with rifle butts smashing against her bones.

Eight-year-old Lam Chun stood frozen. Her sister was tied to the staircase, her shirt staining redder with each blow.

Soldiers demanded stolen military currency she never touched. When she fainted, they revived her with water. When their mother lunged forward, a soldier threw the older woman to the ground. A blade was pressed to Lam Chin’s throat — yet she never yielded.

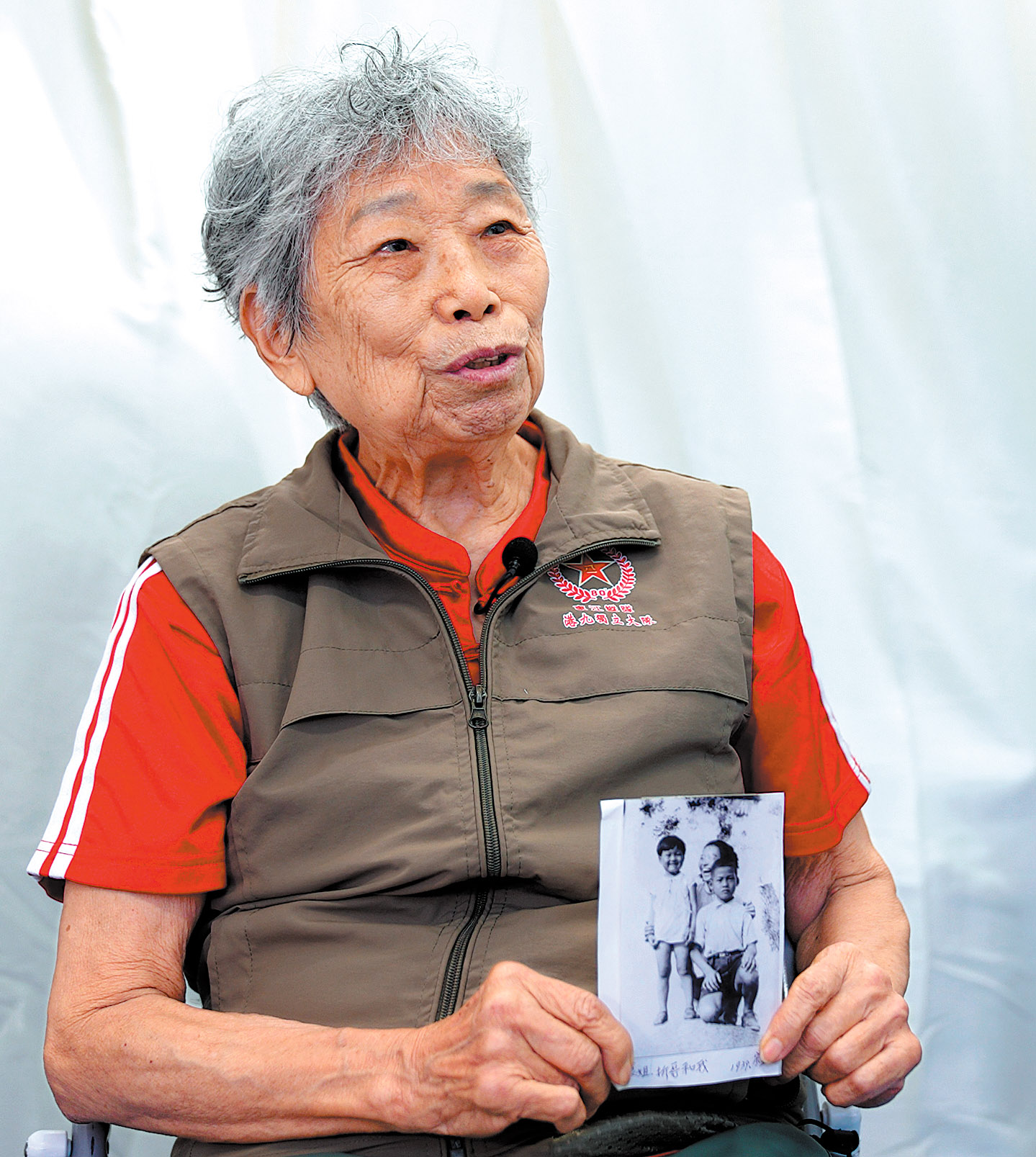

“That day left a deep impression on me,” Lam Chun, now 90, recalled. “It wasn’t a day for just our family’s shame, but also the nation’s suffering.”

The torture lasted hours, finally ending at lunchtime. Having found nothing, the soldiers left — but not before stealing a pair of military binoculars that had belonged to Lam Chun’s late father, a Kuomintang officer.

What her tormentors did not know was that Lam Chin was secretly smuggling intelligence for guerrillas led by the Communist Party of China in their fight to liberate Hong Kong.

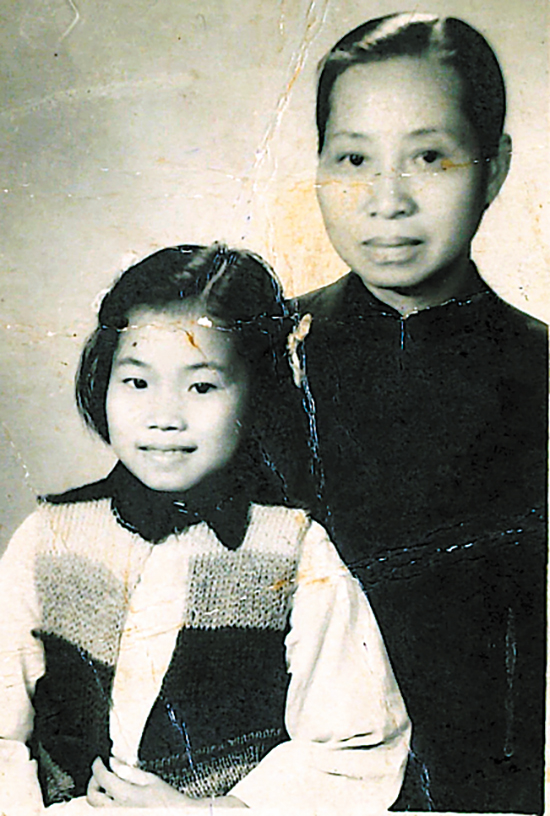

That night, as her family dressed her wounds, Lam Chin revealed her secret. A former leader in the student movement supporting the Chinese People’s War of Resistance Against Japanese Aggression (1931-45), she had long been fighting back.

Her suffering, coupled with this revelation, became a call to arms — not just for vengeance, but for victory.

Within months, Lam Chun, her mother, and her brother joined the Hong Kong Independent Battalion — her sister’s unit. They fled to its Pingshan headquarters in rural Shenzhen in Guangdong province. Lam Chun’s two other older sisters stayed behind in occupied Hong Kong.

Nearly 1,000 strong and composed almost entirely of locals, the battalion became a relentless foe to Japan after its Dec 8, 1941, invasion of Hong Kong.

The then-British colony’s defenses had collapsed in just 18 days.

Now, as the last survivors fade, their stories — once buried under colonial and wartime politics — have resurfaced. Their resistance played a crucial role in the broader Allied effort to defeat fascism and weaken the Japanese war machine.

Dec 8, 1941, began like any ordinary morning in Hong Kong — until warplanes tore through the dawn sky. The Lam family had just finished breakfast when air raid sirens shattered the calm.

Their home, directly across from Kai Tak airfield, placed them in the crosshairs.

The Japanese occupation shattered their lives overnight.

The Hong Kong Independent Battalion traces its roots to the Guangdong People’s Guerrilla Force resisting Japanese aggression — specifically its 3rd and 5th Companies, precursors to the famed Dongjiang (East River) Column.

For three years and eight months, they stood as Hong Kong’s only organized armed resistance, sustained by civilian networks.

“Many Hong Kong families joined the resistance together — fighting as one,” said Lam Chun, now president of the Society of the Veterans of the Original Hong Kong Independent Battalion of the Dongjiang Column.

Few embodied this spirit more than the Law family of Sha Tau Kok, with nine of its 11 members taking up arms as guerrillas.

Born in 1930, Law King-fai grew up amid the resistance efforts. His childhood was defined by the cause and, even as a toddler, he was taught patriotic songs.

The Lams’ journey was part of this collective resistance.

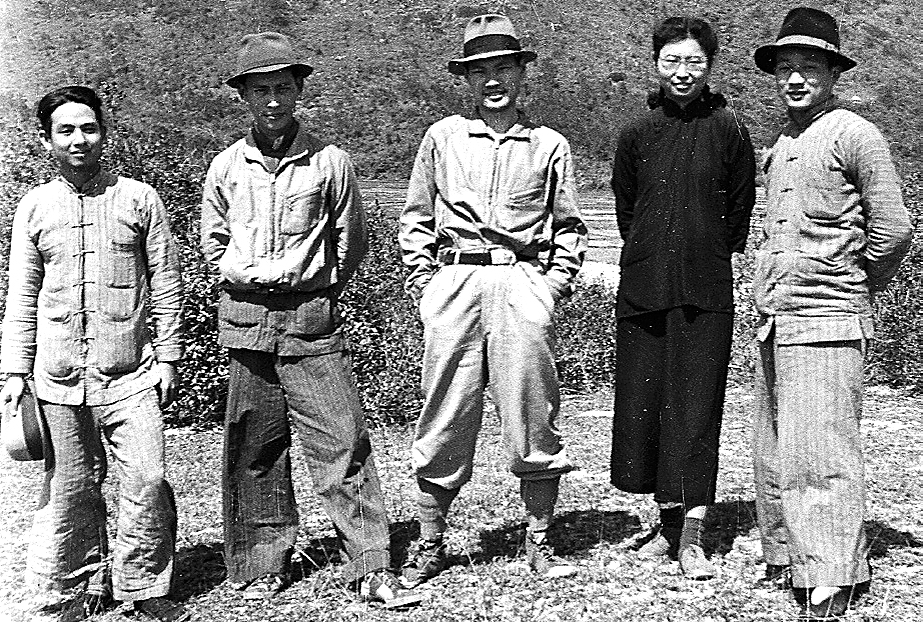

By 1943, Lam Chin was already a member of the battalion’s international work division in charge of translation and intelligence. She also served as a personal interpreter for Dongjiang Column Commander, Tsang Sang.

Her mother was involved in military logistics, proving that even those who had never held a gun could contribute to the fight.

Lam Chun, just a child at the time, was a messenger, threading her way through enemy lines with matchstick-sized intelligence scrolls tucked into her collar or hidden among fruit baskets. She mastered the Hakka dialect and learned to decipher secret trail markers.

In one of the war’s boldest missions, the battalion smuggled over 800 Chinese cultural figures, their relatives, and soldiers of international allies out of occupied Hong Kong.

The city had been a precarious refuge since 1937, when artists, writers, and scholars from the Chinese mainland fled there to avoid Japan’s invasion. They published underground newspapers, staged anti-fascist plays, and broadcast messages of defiance. This made all of them prime targets.

When Hong Kong fell to Japanese forces in 1941, the occupiers moved swiftly to crush China’s intellectual resistance. Propaganda flooded the streets, and cinema screens ordered prominent figures to report for “collaboration”.

Peking Opera legend Mei Lanfang, filmmakers Cai Chusheng and Situ Huimin, and writer Mao Dun were summoned by occupiers under the guise of an invitation.

Trapped in a Cantonese-speaking city where their accents marked them out, escape seemed impossible. Yet a covert network of guerrillas, fishermen, and locals orchestrated their evacuation — sneaking them past checkpoints and through jungle to Free China.

“It was an epic operation — moving 800 people under the noses of the Japanese, undetected for over 200 days,” said Chan Hoi-lun, daughter of guerrilla leader Chan Leung-ming.

Her mother, Tsau Sheung-ling, played a key role. At 20, she disguised herself as filmmaker Cai’s niece, guiding him and his wife past patrols with acting so convincing she fooled the soldiers. They reached a safe house in Central and later escaped to Guilin in Guangxi via Macao.

Her bravery came at a high price. After helping run a Lantau Island resistance base, Tsau was betrayed by a traitor and arrested by the Japanese. Right after giving birth to her daughter, she was seized and tortured. She watched the 12-day-old girl die of malnutrition in prison. Her in-laws were later executed by Japanese troops.

Hong Kong is launching a series of events to educate its youth on national history and commemorate the 80th anniversary of the victory in the war. The initiative includes exhibitions, workshops, film screenings, and exchange tours to historical sites on the Chinese mainland.

The need for such education is felt personally by the likes of Chan Hoi-lun, who said she was excited to hear about the new memorial that began construction on Aug 12 at Silvermine Bay.

The site on Lantau Island is where her father once organized guerrilla fighting and where a tragic massacre unfolded from Aug 19 to 26, 1945. Even after Japan’s surrender, Japanese troops accused villagers of harboring guerrillas, arresting 300 and killing 11 of the bay’s 500 residents.

Upon its completion in October, the Silvermine Bay memorial will join other commemorative sites, including those in Sha Tau Kok in the New Territories, and in Sai Kung’s Wong Mo Ying village and Tsam Chuk Wan.

At a recent forum, Hong Kong Special Administrative Region Chief Executive John Lee Ka-chiu underscored the city’s significant role in China’s war efforts.

In a recent interview with China Daily, Hong Kong lawmaker Chan Yung said that while history education has improved significantly since the 1997 handover, more must be done to strengthen the understanding of national history.

That history remains etched in the memory of Lam Chun. Holding a black-and-white photograph of herself with her older sister and brother taken at Sung Wong Toi Park before the Japanese invasion, Lam recalled how her sister Lam Chin would constantly bring home friends to sing:

My home is on the Songhua River in the Northeast,

Where there are forests and coal mines,

And soybeans and sorghum all over the mountains and fields.

“I would listen and sing along, but couldn’t understand at the time,” she said. “It was not until the 1941 invasion started that I realized they were songs of resistance against Japanese aggression.”

Contact the writer at lilei@chinadailyhk.com