The International Council of Museums now officially lists a number of social roles for museums to play. Chitralekha Basu wonders if Hong Kong Palace Museum is up to the task.

A vase with spiral pattern from the Qianlong period (1735-96). (PHOTO / © THE PALACE MUSEUM)

A vase with spiral pattern from the Qianlong period (1735-96). (PHOTO / © THE PALACE MUSEUM)

In the middle of a video-call interview for this article, Daisy Wang’s office suddenly goes dark. “I’m sorry, we’re in a green building,” says Wang, Hong Kong Palace Museum's (HKPM) deputy director, curatorial and programming, flailing her arms for a bit to prompt the room’s occupancy sensors to turn the lights back on.

Not that long ago, museums were mainly concerned with conserving and showcasing heritage. Today they are expected to serve as disseminators of public good. And since charity begins at home, it’s hardly surprising that HKPM — a "brother" to Beijing’s Palace Museum and therefore majorly invested in the conservation and restoration of Chinese art and antiquities — would want to keep their carbon footprint in check.

Sustainability is high on the list of social responsibilities a present-day museum is expected to fulfill. Accordingly, it’s a significant addition to the new, enhanced definition of a museum, passed by the International Council of Museums (ICOM) on August 24. And since the newly approved museum description, arrived at after years of deliberation, marks a paradigm shift in the roles museums play, this might be a good time to inquire how HKPM — the SAR’s newest museum, having opened to the public on July 3 — is measuring up.

Flowing Script, installation by Chris Cheung, featuring robotic arm, ribbon and multiple video channels. (©HONG KONG PALACE MUSEUM / PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Flowing Script, installation by Chris Cheung, featuring robotic arm, ribbon and multiple video channels. (©HONG KONG PALACE MUSEUM / PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Resonate

Take, for instance, the idea of making museum collections “accessible” in a way that facilitates “the participation of communities” (neither of these aspects figured in ICOM’s previous museum definition, adopted in 2007).

Curiously, getting people through the door seems to be the least of the challenges HKPM faces. Wang says the enthusiasm shown by an overwhelmingly large number of “curious, intelligent and engaged visitors” since the museum’s opening has been unlike anything she experienced in her dozen or so years as a curator at the Smithsonian.

“I was amazed by the rush (of people waiting to try their hand) at the calligraphy station. We had to get them to queue up. That was a happy problem to have,” Wang says.

“We need to improve our logistics and other facilities to be able to accommodate more visitors,” she adds.

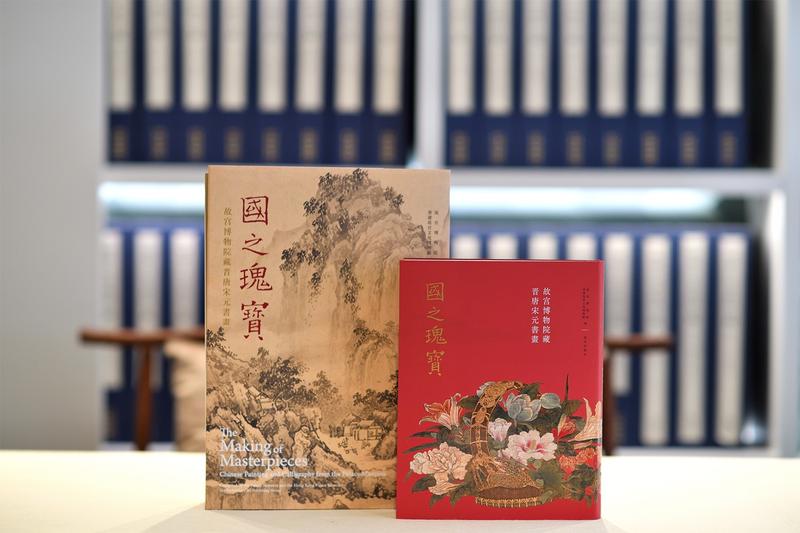

Hong Kong Palace Museum collaborated with the Palace Museum in Beijing to produce the The Making of Masterpieces: Chinese Painting and Calligraphy from the Palace Museum. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Hong Kong Palace Museum collaborated with the Palace Museum in Beijing to produce the The Making of Masterpieces: Chinese Painting and Calligraphy from the Palace Museum. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

From the outset, HKPM has relied on the power of story-telling to reach out, especially, to a younger demographic. The strategy seems to be appealing to Hong Kong people across the board. As museum director Louis Ng said to this writer some months before the museum’s opening: “We will adopt a modern-day approach by bringing traditional art and culture into people’s lives in the present. Each idea or object that we show will be linked to our audience’s experiences.”

It’s an ambitious project, given the bulk of HKPM’s exhibits are sourced from the Palace Museum in Beijing and include items that are 5,000 years old. The loan from Beijing comprises 914 pieces, including 166 Grade 1 objects — many of these personal effects of the Qianlong Emperor (1711-99) or pieces he commissioned. Examples include an exquisitely crafted jade coiled-dragon imperial seal, from the Chongde period (1636-43) of the Qing Dynasty, and Giuseppe Castiglione’s painting (1736-38) showing the emperor enjoying a spot of domestic bliss as he celebrates the Lunar New Year surrounded by children — quite a change of scene from another Castiglione painting showing the emperor in full armor, riding a white stallion (1758).

An oil painting titled The Matilde Moored in Hong Kong Harbour (circa 1850), sourced from Hong Kong Maritime Museum. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

An oil painting titled The Matilde Moored in Hong Kong Harbour (circa 1850), sourced from Hong Kong Maritime Museum. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

If all that seems quaint and distant from the perspective of a Hong Kong audience, Wang points out that 18th century Qing culture has more resonances with present-day Hong Kong than is immediately apparent.

She draws attention to the menu of a banquet the Qianlong Emperor hosted in honor of his mother. Peaches assembled for that feast “are similar to the longevity peaches served as desserts at traditional banquets in Hong Kong to this day”, she notes, adding that such details can help local visitors feel connected to the grand narrative of traditional Chinese culture.

Emperor Qianlong’s seal with jade coiling dragon (1636-43). (PHOTO / © THE PALACE MUSEUM)

Emperor Qianlong’s seal with jade coiling dragon (1636-43). (PHOTO / © THE PALACE MUSEUM)

Interpret

Museums of today are also expected to question mainstream narratives linked to their collections, especially when these have remained entrenched for centuries. As Li Yu-chieh, assistant professor in the Department of Visual Studies at Lingnan University, sees it, “HKPM has a great opportunity to intervene in the conventional narratives of Chinese art histories.”

Such new and alternative narratives developed “from the unique perspectives of the Greater Bay Area ... will have a long-term impact on the identities of local communities and the ways in which Chinese cultures are understood globally”, Li predicts.

Interpreting collections is a crucial addition to ICOM’s newly approved roster of a museum’s duties. HKPM has taken this idea to the next level by inviting six Hong Kong artists to choose an object from the Beijing Palace Museum’s galleries and create new works in response.

Gramophone from early 20th century. (PHOTO / © THE PALACE MUSEUM)

Gramophone from early 20th century. (PHOTO / © THE PALACE MUSEUM)

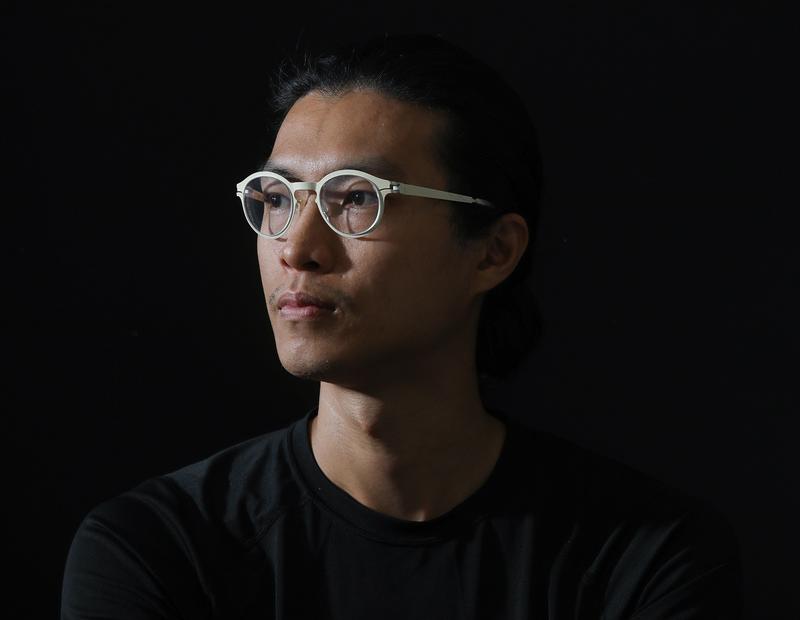

Commissions include Chris Cheung’s installation, Flowing Script, in which a robotic arm wielding a red ribbon “writes” Chinese characters in the air. The piece takes inspiration from Yuan Dynasty scholar Deng Wenyuan’s (1258-1359) handwriting practice text, Jijuzhang. Cheung explains that the piece is his ode to “the disappearing aesthetic of Chinese characters”.

“The next generation of technology will allow us to use brain waves to communicate directly,” he says — an innovation that could make writing, including calligraphy, redundant.

Cheung’s way of passing on the heritage craft was to “teach the robotic arm to mimic the drawing of all 1,394 characters in Deng’s passage”.

Raft-shaped cup (1345) created by Yuan dynasty silversmith Zhu Bishan. (PHOTO / © THE PALACE MUSEUM)

Raft-shaped cup (1345) created by Yuan dynasty silversmith Zhu Bishan. (PHOTO / © THE PALACE MUSEUM)

Include

The very idea of HKPM has been treated with a degree of skepticism since the plan to build it on the southwestern tip of the Kowloon peninsula was announced in December 2016. Among the various complaints — including that by environmentalists who believe the museum’s construction on reclaimed land endangers the area’s biodiversity — are charges that the HKPM project was a fait accompli, passed without public consultation.

Since then, the leaders of the $450-million project have been trying to make amends. Wang says the museum has been inviting representatives from various interest groups — arts and culture professionals and school principals, for example — for sharing and consultation sessions since long before the museum opened.

Marianne Wong, a senior tutor in the Department of Chinese and History, City University of Hong Kong (CityU), attended one such session back in February 2021. She mentions that HKPM is “collaborating with at least three university departments in Hong Kong on arts education projects”, inviting participation from young artists and art educators. “I think this is a clever approach that enables a much wider and more far-reaching impact on the community,” she adds.

CityU academic Marianne Wong says Hong Kong Palace Museum could help foster a stronger sense of national identity in Hong Kong peple. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

CityU academic Marianne Wong says Hong Kong Palace Museum could help foster a stronger sense of national identity in Hong Kong peple. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

The idea ties in with director Ng’s vision: to make “inclusivity a very important part of our learning, engagement and community programs”, hold more women-oriented shows and “cater to those with special needs and from disadvantaged groups”. While it might take a few years for a fledgling museum like HKPM to reach these goals, Hong Kong’s culturally invested expect nothing less.

“My expectations of a museum like HKPM are that it will foster the education and participation of local communities — for instance, by having a docent program that involves diverse social groups, and research programs that support emerging scholars to study cultures in critical ways,” says Li.

She also hopes that HKPM will, eventually, resurrect “voices from the frontiers of Chinese art histories”, in line with efforts to decolonize museum collections and wall texts — a worldwide trend since well before the new ICOM definition, which lists fostering inclusivity and diversity among the core tasks of a museum, was approved.

Li Yu-chieh, assistant professor of visual studies at Lingnan University, says, “Hong Kong Palace Museum has a great opportunity to intervene in the conventional narratives of Chinese art histories.”(PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Li Yu-chieh, assistant professor of visual studies at Lingnan University, says, “Hong Kong Palace Museum has a great opportunity to intervene in the conventional narratives of Chinese art histories.”(PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Educate

Of all the responsibilities on ICOM’s list, HKPM’s progress in the area of “offering varied experiences for education, enjoyment, reflection and knowledge sharing” is actually quantifiable.

“We’re working on an ambitious project to bring over 100,000 students to HKPM for gallery tours and curated experiences,” Wang shares.

HKPM collaborated with the Hong Kong Education Bureau on a Chinese history teaching resource book. Every history teacher in Hong Kong has received a copy, and a PDF version is available for free download on the Education Bureau’s website.

“We collaborate with artists and curators to design resource materials for teachers,” explains Wang. “They contain guidelines on using museum treasures as classroom teaching aids — while talking about emperors and their ruling principles, for example.”

HKPM’s deputy director, curatorial and programming, Daisy Wang reveals that the institution recently acquired nearly 1,000 priceless objects. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

HKPM’s deputy director, curatorial and programming, Daisy Wang reveals that the institution recently acquired nearly 1,000 priceless objects. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

HKPM’s publication team also works closely with its Beijing counterpart. The two recently teamed up to bring out an English version of the recently released The Making of Masterpieces: Chinese Painting and Calligraphy from the Palace Museum.

“This is something we’re uniquely positioned to do,” says Wang. “The book contains information on seals, inscriptions and so on, and required inputs from specialists to make the descriptions accessible to an international audience. (At HKPM), we have a diverse international curatorial and publication team, and hence the ability to produce reading material for an international audience.”

Chris Cheung pays homage to “the disappearing aesthetic of (handwritten) Chinese characters” in his Hong Kong Palace Museum-commissioned installation, Flowing Script. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Chris Cheung pays homage to “the disappearing aesthetic of (handwritten) Chinese characters” in his Hong Kong Palace Museum-commissioned installation, Flowing Script. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

The road ahead

Starting life as a subsidiary of the Palace Museum in Beijing, HKPM appears ready to come into its own. Wang reveals that HKPM is all set to make its first round of acquisitions — “a wonderful collection of nearly 1,000 objects, including a very distinguished collection of gold objects sourced from the mainland”. Besides, the number of queries from prospective donors in possession of Chinese antiquities has been growing.

At the end of the day, the measure of a museum’s success lies in whether it’s able to add social value to the land on which it stands.

While it’s premature to wonder whether HKPM might, one day, evolve into what the Louvre is to Paris, or the British Museum to London, those tasked with developing the museum as China’s bridge with the rest of the world are sparing no effort.

Wang is confident that HKPM will be “a tourist hotspot” once quarantine-free travel resumes. The museum is also banking on “tourists from the Greater Bay Area and elsewhere on the mainland” in due course.

CityU’s Wong believes the inclusive, cosmopolitan outlook of Hong Kong people will aid HKPM on its journey to becoming a world-class institution. “Hong Kong people are familiar with promoting cultural development through collaboration and cultural exchanges,” she points out.

What Hong Kong stands to gain from this process is a better understanding of its place in the national framework. When a Hong Kong person stands in front of a Qing ceramic vase with red, white and blue spirals, and is struck by its resonance with the city’s generic, plastic packaging material, it might be easier to believe in, as Wong puts it, “a more defined national identity and a stronger sense of belonging in their relationship with the rest of China”.