The writing of Chen Nianxi not only taps into the rich vein of material provided by his career blasting ore in mines around the country, but also gives voice to society's 'invisible' people, Yang Yang reports.

Chen sitting in front of his old house in Xiahe village, Shaanxi, in 2018. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Chen sitting in front of his old house in Xiahe village, Shaanxi, in 2018. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

In a world where it seems that everyone has a voice online, few people's voices can really be heard; In a world where, superficially at least, the internet has entitled people to better understand diversity, the gaps between generations, countries and opportunities remain, and in some cases, seem to be growing.

That is why many people, when reading the poems and essays of former miner Chen Nianxi, are at first surprised and then moved.

In his writing, he uses a restrained voice to describe his life as a miner, working 5,000 meters underground, as well as his fellow miners, his family, friends, acquaintances, people who would have perished silently if he had not recorded their passing, poverty, accidents, injuries, deaths, diseases and pain, along with his travels around China and his observations, thoughts and feelings.

Chen was born in a small village called Xiahe, south of Qinling Mountains in Northwest China's Shaanxi province-one of the most poverty-stricken areas in China-in 1970. It was in this barren place where he spent his early years.

When he went to high school at the end of the 1980s, China had entered a period when poetry had become a popular literary genre widely read around the country. A lot of people wrote poems and Chen was one of them.

He remembers that both his grandfather and father's generations could sing xiaoge, a performance prevalent at local funerals. Three days before the burial, a group of people would circle around the coffin, singing songs, the complicated lyrics of which interweave historical stories, folklore and even the personal experiences of the singers.

"Actually in my poems, sometimes the lines don't rhyme, but there is a basic tone. People who are familiar with those funeral songs might be able to tell the difference," he says.

In the 1990s, when he worked at the family's farm and herded cattle in mountains, he read extensively, including Karl Marx's Capital, and wrote a lot of "naive", "romantic" poems, he says.

That idyllic time ended when he got married in 1997 and his son was born in 1999.

"My wife and I tried our best to work, but although the food and vegetables growing on our own farm could feed the family, and we could make some money from selling the pigs we raised, there was no other income," he says.

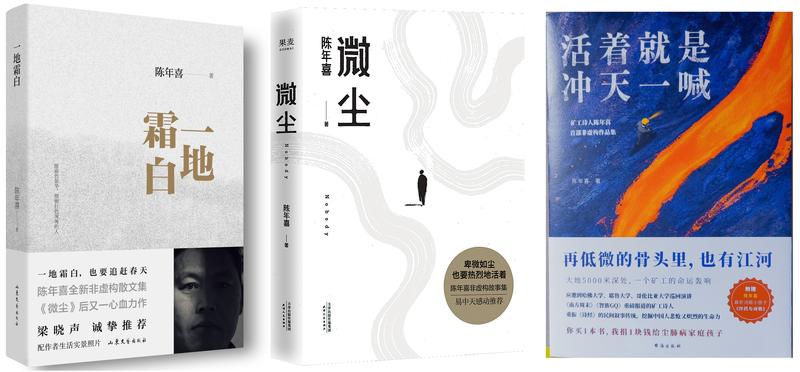

From left: Three nonfiction books by miner-turned-writer Chen Nianxi, which were published last year and this year-Yidi Baishuang (Ground Covered With Hoarfrost), Weichen (Nobody) and Huozhe Jiushi Chongtian Yihan (To Live Is to Roar at the Sky). (PHOTOS PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

From left: Three nonfiction books by miner-turned-writer Chen Nianxi, which were published last year and this year-Yidi Baishuang (Ground Covered With Hoarfrost), Weichen (Nobody) and Huozhe Jiushi Chongtian Yihan (To Live Is to Roar at the Sky). (PHOTOS PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

At the turn of the millennium, Chen published his first two poems and got 40 yuan ($6.30), with which he bought several bags of milk powder for his son. But it happened only once. One evening, he got a message from a classmate saying that a mine needed a carman, so Chen packed his luggage, and started his career as a miner.

For 16 years, Chen traveled across the country to work in different mines, from both ends of the Xinjiang Uygur autonomous region to Qinghai province and the Inner Mongolia autonomous region, and from Jiangxi to Guangdong provinces, witnessing many moments of danger and death, recording his observations, feelings and thoughts in poems.

Verses came to him while he was drilling holes in tunnel walls; sometimes he bent over the dynamite boxes writing poems to kill time; sometimes he would spontaneously record his feelings on scraps of paper and cigarette boxes.

In 2011, he arrived in a deserted area of Karamay, Xinjiang, to work in a mine, and slept in an underground room along with a "slagger"-someone who removes the waste material from the worksite-who would leave for work when Chen would get back from his shift underground.

The bunk bed was very thin. As a blaster, Chen placed empty dynamite boxes he brought back with him under the mattress. In this "no man's land", there was no paper available. To avoid boredom during his downtime, he would write poems on the boxes.

One year later, when he decided to leave and he packed his bedclothes, he found that his poems had covered all the boxes. However, the boxes were disposed of, so were the poems, like many of those he had written before.

In the following years, blogs became popular in China. Chen got a smartphone and registered a blog account, where he started to post his poems.

Gradually, he attracted a large number of readers and, in 2015, he was featured in a documentary The Verses of Us together with five other migrant worker poets. In 2016, he went to the United States to talk about his poems at universities such as Harvard and Yale.

In a speech, he said, "There are souls in the 'humblest' bones! I write poems, because I've got things to say. I know in this world, quite a lot of people, even the families and friends of migrant workers, know very little about their work and lives. This is actually a time of infinite alienation. There are such big gaps between generations, countries, and fates."

Chen writes in his new house in Danfeng city, Shaanxi province, in October 2021. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Chen writes in his new house in Danfeng city, Shaanxi province, in October 2021. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Reading The Book of Songs, Chen got to know the time and mindset, as well as the misery and pain, of ancient China, and understood that real poetry is a historical record of the reality and mindset of the era in which it is written.

"There are 7 billion people in the world, and only a very few people's voices can be heard. Those silent souls, when they can finally speak, what are they going to say?"

In one of his most well-known poems, A Record of Explosion, he wrote:"I daren't take a look at my life. It's hard, pitch black. Sharp like an air pick. It bleeds once abraded by rocks.

"I killed my middle age 5,000 meters under the ground. I cracked the rock strata again and again with dynamite. So that I recomposed my life.

"My little family, at the foot of Shangshan Mountain far away. They're sick, their bodies covered with dust. How much I can cut from my middle age. How much longer can they live.

"I had 3 tons of dynamite in my body. They (the family) are the detonators. Just at last night. I exploded, like rocks, falling over the place."

In the 16 years working underground, Chen narrowly escaped death many times, but he could not escape other injuries. One accident caused him to go deaf in his right ear and caused nonstop booming in the left.

Working 10 hours in tunnels no more than 1.8 meters high has resulted in him suffering neck issues, which could lead to paralysis if not treated in time. The dusty working environment caused pneumoconiosis, which will gradually consume his life.

In April 2015, he underwent a vital operation on the fourth, fifth and sixth cervical vertebrae, where metal implants were added to keep the bones in place. Chen decided to use implants imported from the US, although they were more expensive.

"These exquisite pieces, produced in the US, were perhaps made from some of the ore that I helped extract from the pitch-black deep mountains. Transported far away to the US and turned into medical devices, it then traveled back across the ocean and became part of my body," he says.

In 2016, Chen won the first Worker Poet Laureate Prize. Commenting on his poems, the jury said that Chen used poetry to think about the fate of common workers in the globalized world, taking worker poetry to a new height. The cervical operation ended Chen's mining career. In the autumn of 2015, he came to Beijing for a TV program and stayed. After working in Picun for a year, he was introduced to a tourist company in Guizhou province as a publicity staff member.

Since the end of 2017, he started writing a column for The Paper in his free time. In 2018, an article, The Last Ten Years of a Rural Carpenter, went viral online, in which Chen used 6,000 words to write about his father, a carpenter in the countryside.

In May 2021, the 21 articles of his newspaper column became his first book, Wei Chen (Nobody), telling the stories of people whose hard lives were little known. In June, his second essay collection, Huozhe Jiushi Chongtian Yihan (literally, To Live Is to Roar at the Sky) was released, telling more about the hard life of miners, the invisible people in the society, death, love, pain, struggle, the COVID-19 pandemic, and his writing.

Like his best-selling poem collection Zhaliezhi (A Record of Explosion), published in 2019, these nonfictional writings have also been well-received by readers and critics. The two books have, together, sold more than 130,000 copies, and appeared on a number of different lists of top nonfiction books in 2021.

Commenting on Wei Chen, Zhang Li, professor of Chinese literature with Beijing Normal University, says: "He is a good writer by my standard. I've never thought about his profession. I respect all kinds of writers, whether they are farmers or workers, but the most important thing for me is the quality of writing."

Diagnosed with pneumoconiosis in 2020, Chen, now a professional writer, lives in his hometown. His new nonfiction book, Yidi Baishuang (literally, Ground Covered With Hoarfrost), was published recently, and he is now revising Chen Nianxi De Shi (Poems by Chen Nianxi), a new collection of poems.

Contact the writer at yangyangs@chinadaily.com.cn