Ten years in the making, Hong Kong’s new global museum of contemporary art is finally ready to face the public. M+ insiders and industry-watchers share their views on the museum’s present and continuing relevance with Chitralekha Basu.

Both art historian and curator Ole Bouman and Lingnan University academic and museum expert Selina Ho mention “adventure” while sharing their views on M+ — Hong Kong’s new global museum of visual culture — which opens to the public on Friday. “Adventure” could well be one of the key words to describe the museum that has been part of Hong Kong’s cultural life since at least a decade ago, when its first core team of executives, under the leadership of then-executive director Lars Nittve, kicked off a series of public engagement activities.

Adventure was quite literally the name of the game in Inflation — one of M+’s earliest pop-up exhibitions in 2013, held on the rolling green meadows of West Kowloon Cultural District, where the museum stands today. The show drew over 100,000 visitors. The young and young at heart happily took a tumble between the pillars of Jeremy Deller’s Stonehenge-meets-bouncy castle piece, titled Sacrilege — one among several other soft, inflatable, monumental sculptures that also included Paul McCarthy’s excreta-shaped Complex Pile.

“It was a very different idea of sculpture, and that immediately established M+’s mark. People had a lot to say about the exhibits,” M+ Museum Director Suhanya Raffel remarks.

Suspended from a high ceiling, Young-Hae Chang’s five-channel video installation has a larger-than-life aura. (CHITRALEKHA BASU / CHINA DAILY)

Suspended from a high ceiling, Young-Hae Chang’s five-channel video installation has a larger-than-life aura. (CHITRALEKHA BASU / CHINA DAILY)

Such appetite for departure from the norm is in evidence, once again, left, right and center, in M+’s 17,000-square-meter display space spanning 33 galleries, showcasing 1,500 exhibits from the museum’s ever-growing collection of often-atypical and groundbreaking art as part of its six inaugural exhibitions.

A playful spirit informs the interactive museum experiences on offer — from soundscapes presented with “unexpected audio-visual stimulation,” created by multimedia artist Gaybird, to the Moving Playground-designed Body Game, where children between 3 and 8 are encouraged to use their body parts to make art. Among the exhibits is a rusty ball joint from Osaka’s Expo Tower (1968), designed by Kikutake Kiyonori, and a plastic water dispenser on wheels repurposed as a chair by strapping a cushion on top — a found object gifted to the museum by the photographer Michael Wolf, known for his intense portraits of Hong Kong’s back alleys. By inviting viewers to observe and engage with such objects, M+ is putting out the idea that it’s possible to have a meaningful, open-ended conversation about art without the participants having to take themselves too seriously.

A ball joint from Osaka’s Expo Tower designed by Kikutake Kiyonori looks special when observed in its sociohistorical context. (CHITRALEKHA BASU / CHINA DAILY)

A ball joint from Osaka’s Expo Tower designed by Kikutake Kiyonori looks special when observed in its sociohistorical context. (CHITRALEKHA BASU / CHINA DAILY)

Touching people’s lives

The extent to which a museum can connect with a demographic other than art enthusiasts, scholars and those with a stake in the industry is a key measure of its relevance. Launching at a time when Hong Kong remains off-limits to nonresidents, M+’s efforts to reach out and build sustained relationships with the local community remain critically important. As Ho, the acting head of the Department of Visual Media at Lingnan University, says, “M+ will have to be more community-facing, by supporting community-based artistic practices and collective curation; conceive more inclusive and polyphonic approaches to collecting, curating and interpreting; mediate art as a tool to empower community members; and shape the narratives and experiences that matter and are relevant to their lives.”

It’s a long and ambitious wish list. Reassuringly, M+’s learning and interpretation team has been working toward roughly similar goals for some time. M+ Rover, the museum’s mobile interactive showcase that earlier visited Hong Kong schools and community centers, went online in 2020. During the months of pandemic-induced closure of schools, it had managed to connect with over 45,000 students virtually.

Now that M+ has a home, audiences are invited to claim a share in it. Among the visitor experiences meant to inspire a sense of museum ownership and facilitate impromptu community bonding is an interactive game Raffel particularly recommends. The Cabinet is inspired by the idea of the Wunderkammer, i.e., the Cabinet of Curiosities, which was a staple of “19th-century museums as a way of collecting numerous interesting things that were unrelated and presenting them together as curiosities.”

“The Cabinet is actually an open storage system of 40 movable panels housing 200 artworks. It amplifies the accidental connections that individuals have when they are looking at many things at the same time. It’s an open-ended interactive conversation to exchange ideas, information and thoughts about what you are seeing, through a very playful structure,” Raffel explains.

Cao Fei’s RMB City series of videos is presented as a hybrid experience, combining physical objects with screenings and interactive digital interfaces. (RAYMOND CHAN / CHINA DAILY)

Cao Fei’s RMB City series of videos is presented as a hybrid experience, combining physical objects with screenings and interactive digital interfaces. (RAYMOND CHAN / CHINA DAILY)

Art by chance

In fact, the Wunderkammer is at the heart of one of M+’s six opening exhibitions: The Dream of the Museum. This one was probably a no-brainer though. M+ has acquired the largest collection of works by Marcel Duchamp in Asia through Uli Sigg — who also donated his collection featuring 325 major Chinese artists active from the 1970s onwards to the museum. When viewed side by side, the resonances between the works by the French pioneer of conceptual art and his Chinese spiritual progeny became all too evident to M+’s curatorial team.

“So many Chinese artists, including Huang Yongping who began a kind of Dada movement in China, cited Duchamp as an inspirational figure although they never got to see his works in the original,” Raffel points out.

Some of these “unexpected parallels” cut further across time and space, as Doryun Chong, deputy director, Curatorial and chief curator of M+, points out. For example, traces of Emperor Qianlong’s square sandalwood curio case in the palace museum in Taipei seem to resurface in Duchamp’s seminal work, Boîte-en-valise, “which the artist called a ‘portable museum’ dedicated to his life’s work,” Chong says.

“From the 18th to the 20th century, and across cultures between Asia and the West, artists and collectors have dreamed about what a museum or collection could be. As conceptual methods of art-making developed in more recent decades — including powerful notions such as chance and readymade — artists all over the world could come up with more and more innovative and unconventional artistic expressions, boldly exploring and updating their own cultures and histories, as well as the everyday. The broad range of possibilities created by artists together make and enrich ‘the dream’ of museums like M+,” Chong says, explaining the scope of the exhibition whose spirit aligns with a core idea informing M+’s overall curatorial vision.

Mediatheque is M+’s moving image library, offering a range of screen-on-demand videos, besides VR and gaming experiences. (RAYMOND CHAN / CHINA DAILY)

Mediatheque is M+’s moving image library, offering a range of screen-on-demand videos, besides VR and gaming experiences. (RAYMOND CHAN / CHINA DAILY)

Where the past meets future

Many of the items in M+’s collection are already familiar to Hong Kong’s art lovers. Highlights from the 6,413 works of art acquired by the museum (as of June 2021) as well as those from the 1,510-strong Uli Sigg Collection are free to access on the museum website. Besides, over the last eight years, M+ has hosted a number of curated off-site shows featuring material selected from its collection — the stunning, iconoclastic architecture designs by Zaha Hadid, and red Manolo Blahniks worn by Cantopop legend Leslie Cheung, to cite just two examples.

The curiosity at this moment therefore is mainly centered around the new commissions and perhaps unsurprisingly, many of these are digital works of art.

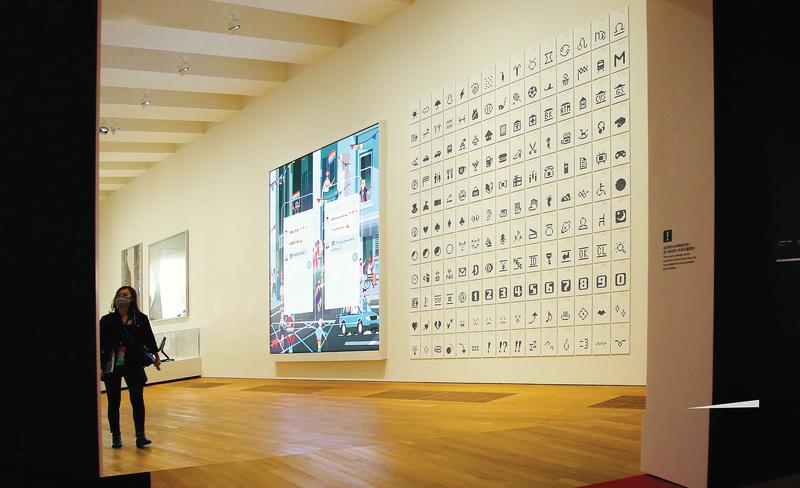

The range is mind-blowing. Highlights include Young-Hae Chang’s site-specific larger-than-life video installation in the shape of a crucifix, throwing up a series of irreverent graffiti, comicbook graphics and photos in lurid colors superfast, challenging the viewer’s capacity to register them all. Hoisted in M+ Focus Gallery, the piece is strategically placed to let shafts of sunlight come in through the small windows close to the ceiling, like in a prison cell. Video production house Jiu Jik Park has created a giant interactive digital screen that answers emoji-related queries from viewers, while the piece hung next to it is a chart showing the earliest versions of emoji, developed in 1999 by Japanese telecommunication company NTT Docomo Inc. and designed by Kurita Shigetaka and architect Aoki Jun. Kong Khong-chang’s Flower in the Mirror — a single-channel animation video installation with a psycho pop aesthetic that seems to channel Yayoi Kusama — is hung in a tunnel-like space to amplify the piece’s loud, surrealist tones.

A live emoji screen complements an artwork showing the earliest versions of the digital icon developed by NTT Docomo Inc. (RAYMOND CHAN / CHINA DAILY)

A live emoji screen complements an artwork showing the earliest versions of the digital icon developed by NTT Docomo Inc. (RAYMOND CHAN / CHINA DAILY)

“There isn’t a particular style or direction we are looking for in digital/tech-driven art,” Chong says. “But one question we consistently ask about potential collaborators or works is whether they ask critical, probing questions about digital technology and experience, while harnessing the unique features of capabilities of this new medium. We are less interested in digital as a mere update on older or classical mediums like painting or video art.”

Besides art powered by the latest technology, M+ is also showcasing the evolution of technology in cultures across Asia. Cao Fei’s RMB City series of 33 videos, for example, is presented like a retrospective show. Created between 2007 and 2011, the series tells the story of the rise and ultimate destruction of a fictitious Chinese city. The videos were created using what might now come across as outdated digital videography tools. The avatars in them come across as prototypes. The low-resolution images of landmark projects symbolic of China’s urban development from Beijing and Shanghai are painted in a limited range of colors that tend to overlap.

The immersive RMB City show is M+’s homage to a milestone in the history of digital filmmaking — the moment when the possibility of making films using only a laptop and an internet connection to assemble the components online was confirmed. There is also a side-show of objects — hard hats and shovels apparently used by “characters” who dug their way through the debris of the RMB City, apotheosized like museum pieces inside a glass case.

“My intuition is that the breadth of the M+ collections and the curatorial choices will help M+ to quickly gain relevance and become a cultural interface between China and the international museum discourse,” says Bouman, the founding director of Shenzhen’s Design Society museum.

Indeed, this is one of M+’s key ambitions, which aligns with the Chinese government’s plan to help develop Hong Kong into a hub of cultural exchanges between China and the rest of the world as part of the nation’s 14th Five-Year Plan (2021-25). Hong Kong is now vested with the responsibility to play an ambassadorial role on behalf of Chinese art and culture and M+ is expected to be a key driver in this endeavor.

Museum 2050 co-founder Nicole Ching is impressed by the range of “in-depth resources” at M+’s disposal, and the “transparency and accessibility” of its online content. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Museum 2050 co-founder Nicole Ching is impressed by the range of “in-depth resources” at M+’s disposal, and the “transparency and accessibility” of its online content. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

The road ahead

More than 10 years in the making, M+ has courted its share of controversies along the way and if anything the odds seem to have grown heavier over time. Writers obsessively wonder why the museum is not displaying a particularly sensitive piece of art as part of the opening exhibitions. Environmentalists point out that M+ is built on a reclaimed piece of land, accusing West Kowloon of trying to legitimize messing with the local ecological balance by “artwashing”. Various high-profile media catering to the Anglophone world routinely worry as to whether it’s still possible to have a free discussion on art in Hong Kong.

Such criticisms will probably start losing their edge once M+ is able to establish a track record of serving a broad range of interests, by getting both museum virgins and seasoned art historians to sign up.

Nicole Ching, who co-founded Museum 2050, a platform to hold conversations around the future of China’s museums, says M+ might be already on its way to achieving this goal.

She is impressed with the way M+ is trying to construct an alternative visual art discourse, by creating a space “especially for those that have not previously had a voice in the Western canon”.

“The kind of transparency and accessibility M+ is trying to achieve, in more than one language, nonetheless, is truly laudable,” she says, referring to the content available online. “It takes a lot of work behind the scenes to allow for that kind of access, and I’m so grateful to have in-depth resources from the museum at my disposal, no matter where I am in the world,” she adds.

Doryun Chong, deputy director, curatorial and chief curator, M+, says The Dream of the Museum show highlights “unexpected parallels” between objects, cutting across space and time. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Doryun Chong, deputy director, curatorial and chief curator, M+, says The Dream of the Museum show highlights “unexpected parallels” between objects, cutting across space and time. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Ho of Lingnan University contends it might not be enough for M+ to put Hong Kong “onto the global cultural map” unless it’s “able to draw dynamic interactions between the global and local”. Indeed what M+ achieves in terms of putting Hong Kong artists and art traditions on the world stage would be the thing to watch. However, this is already part of M+’s remit. Since 2013, the museum selects artists to represent Hong Kong at the Venice Biennale, supports them with curating and mounting the show, and subsequently hosts a return exhibition in the city, creating a new experience based on the original Venice version.

Bouman contends M+ is on solid ground, now that Hong Kong is promoted as China’s window on the world. “The integration of the cultural infrastructure and exchanges between the different key players in the Greater Bay Area provides a solid base for a new museum’s future relevance,” he says.

At the end of the day, the true measure of the efficacy of a museum probably lies in whether it’s able to bring value to the lives of its audience, or what Ho outlines as “whether it is able to uphold a futuristic thinking through experimental art and change-driven projects.”

Industry-watchers feel M+ has the wherewithal to pull it off.

“I feel M+ is positioned to be a leader in showing ways in which cultural institutions can become guardians of creative optimism and solid platforms of the highly necessary inspiration we need to summon to stay afloat,” Bouman says.

“Between now and 2050, I can only imagine M+’s collection of art from all over the region as well as its commitment to telling stories from Hong Kong and elsewhere will continue to grow,” says Ching.