Temples and other intriguing sites draw the crowds to a city where multicultural tradition is part of its modern appeal, Wang Kaihao reports.

An aerial view of the Anping Bridge, once a lifeline in Quanzhou's transport network centuries ago. (SONG QI / FOR CHINA DAILY)

An aerial view of the Anping Bridge, once a lifeline in Quanzhou's transport network centuries ago. (SONG QI / FOR CHINA DAILY)

Buddhist pilgrims and visitors bring hustle and bustle to this famed temple in the historical quarter of Quanzhou, Fujian province.

As one of 22 monuments included in the "Quanzhou: Emporium of the World in Song-Yuan China", Kaiyuan Temple is part of the city's recently gained UNESCO World Heritage status. But it has always been a top attraction for visitors to Quanzhou.

First built in 686, the biggest Buddhist temple in Fujian was given its current name in 738 during the Kaiyuan era (713-741), in the first half of the reign of Emperor Xuanzong of the Tang Dynasty (618-907). The era witnessed the dynasty's pinnacle and many temples around China were bestowed with the same name to mark that prosperous time. But the one in Quanzhou is arguably the most famous.

Luoyang Bridge represents the country's pinnacle of engineering in the Song-Yuan period (960-1368). (WANG KAIHAO / CHINA DAILY)

Luoyang Bridge represents the country's pinnacle of engineering in the Song-Yuan period (960-1368). (WANG KAIHAO / CHINA DAILY)

In the eyes of locals, its psychological significance is exceptional. The 40-odd-meter-high twin stone towers from the Song Dynasty (960-1279) stand sentinel-like above the ancient city's skyline. They ubiquitously appear on posters promoting Quanzhou as the most conspicuous landmarks of the city and are symbols of nostalgia for those far from home.

The main hall architecture demands attention for its splendor. It is not only the exquisite colorful decorations on the roof, but also the 24 sets of wooden buttresses, in the shape of flying Buddhist deities, supporting that roof.

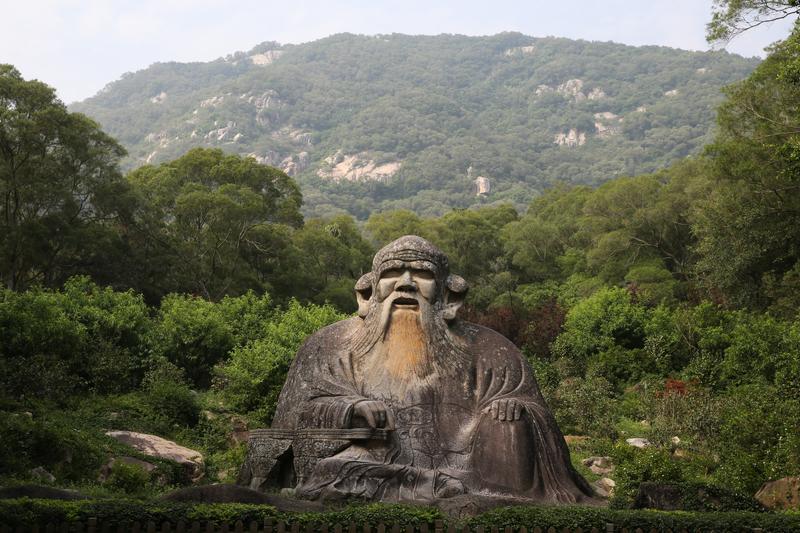

The statue of Lao Tze in Quanzhou is the country's largest surviving Taoist stone-carved statue. (CHEN YINGJIE / FOR CHINA DAILY)

The statue of Lao Tze in Quanzhou is the country's largest surviving Taoist stone-carved statue. (CHEN YINGJIE / FOR CHINA DAILY)

Without the guidance of Shi Deyuan, a monk in charge of conservation and receiving visitors in the temple, one may easily walk by the stone base of the main hall without paying it much attention.

But it is special: 73 stone carvings of lions or deities with human faces and lion bodies indicate their past may be linked with something other than Buddhism.

"They resemble Hindu temples in the south of India during the Chola Dynasty (third century BC-AD 13th century)," Shi says. "It reveals a piece of precious information: there was a Hindu temple in Quanzhou before the 13th century whereas other places in ancient China rarely had such a structure."

A Song Dynasty (960-1279) coin unearthed from Xiacaopu site. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

A Song Dynasty (960-1279) coin unearthed from Xiacaopu site. (PHOTO PROVIDED TO CHINA DAILY)

Hindu decorative patterns are also visible on the stone pillars along the corridor of the main hall. Among the 24 pieces of relief on the pillars, nine are about Hindu deities, including Shiva, Vishnu, Krishna, and other stories from epics such as Mahabharata and Ramayana.

"But local styles also influenced the form of the pillars and its Hindu patterns," Shi explains. "Their counterparts in southern India have a more realistic style while these carvings are more impressionistic, showing a mixture of different cultures."

When the main hall of Kaiyuan Temple was rebuilt in 1637, these building materials were moved from the abandoned Hindu shrine to this site.

"In a well-established Buddhist temple, which had almost a one-millennium history by then, people would use architectural components from Hinduism in renovation," Shi says. "It's a rarely seen cultural phenomenon, but it just shows inclusiveness of Quanzhou culture, which is deeply rooted in the tradition of this city."

Porcelain relics found in the shipwreck of Nanhai One. (WANG KAIHAO / CHINA DAILY)

Porcelain relics found in the shipwreck of Nanhai One. (WANG KAIHAO / CHINA DAILY)

East-West communication

Quanzhou, which witnessed a booming maritime trade from the 10th to 14th centuries, is like a gateway embracing a multicultural community.

"Trade brought Quanzhou not only an influx of goods from all over the world," says Huang Haojing, a researcher at Quanzhou Maritime Museum.

"During the Song-Yuan era, a large number of foreign merchants came to live here. They participated in social affairs and married Han Chinese. Some even became officials. They gave Quanzhou a distinctively cosmopolitan characteristic."

In Jinjiang, Quanzhou, Cao'an Temple on the cliff seems isolated.

A relic unearthed from the site of Southern Clan Office. (WANG KAIHAO / CHINA DAILY)

A relic unearthed from the site of Southern Clan Office. (WANG KAIHAO / CHINA DAILY)

When it was first built in the 10th or 11th century during the Song Dynasty, the temple was made from thatch. That also explains its name Cao'an, which means "a temple of thatch". In 1339 during the Yuan Dynasty (1271-1368), a stone chamber was added.

Lacking any ostentatious appearance, far away from the commercial district, the simple-looking temple is like a perfect place for a hermitage, and it has reason to be included in the 22 monuments across Quanzhou becoming World Heritage sites.

A statue of Mani in the stone chamber, also carved in 1339, is the world's only surviving rock carving depicting the main god of Manichaeism, a worldwide religion active from the third to 15th centuries, according to Wu Jinpeng, director of Jinjiang Cultural Heritage Conservation Center.

Manichaeism originated in Persia during the third century on the basis of Zoroastrianism. It was introduced into Quanzhou in the ninth century, and was then known in China as "the religion of light".

"That religion was quite adaptive," Wu says. "When it spread to the West, it absorbed some doctrines of Christianity, and when it came to the East, it fused with Buddhism, and was thus acceptable for locals. Manichaeism is a perfect example of East-West cultural communication."

A Dehua porcelain jar found in Nanhai One. (WANG KAIHAO / CHINA DAILY)

A Dehua porcelain jar found in Nanhai One. (WANG KAIHAO / CHINA DAILY)

Manichaeism had no idolatry in its original tradition, and that explains why Mani statues were so rare around the world. However, during the Yuan Dynasty, when Quanzhou became a world-class trading center and its rulers showed great inclusiveness toward various religions in the city, Manichaeism became localized at a deeper level.

"Consequently, this statue of Mani in Cao'an wears a Taoist robe while he sits on a lotus throne, which is a typical Buddhist image," Wu says. "And its appearance was also influenced by folk beliefs of the local community."

A group of contemporaneous stone inscriptions by the statue also offer a precious reference for people to see the doctrines and rituals of Manichaeism, as well as how it was developed in Quanzhou.

Manichaeism in Quanzhou faded away during the Ming Dynasty (1368-1644), but the statue remained and was protected by locals for generations as their patron god.

"The statue survives to testify to a dialogue between foreign and indigenous cultures," Wu explains.

A Christian gravestone unearthed in Quanzhou. (WANG KAIHAO / CHINA DAILY)

A Christian gravestone unearthed in Quanzhou. (WANG KAIHAO / CHINA DAILY)

Numerous religious relics in Quanzhou may combine to portray a harmonious picture on cultural diversity during the Song-Yuan era, ranging from the Christian tomb stones exhibited in the Quanzhou Maritime Museum to the Qingjing Mosque, which was first built in 1009 as the first mosque in the city, also part of the World Heritage inscription. The mosque was rebuilt in 1310 thanks to the patronage of a pilgrim from Shiraz, Iran. It thus features the typical medieval Middle Eastern architectural style.

In the archaeological ruins of Deji Gate site-the southern gate of ancient Quanzhou city which is also among the 22 inscribed heritage sites-Christian and Islamic patterns were even found on the same stone carving.

In spite of all the diverse cultures gathering in this harbor, the indigenous culture in Quanzhou during the Song-Yuan era still proved its vitality and influence through other temples included in the World Heritage List.

A Hindu stone carving in Kaiyuan Temple. (WANG KAIHAO / CHINA DAILY)

A Hindu stone carving in Kaiyuan Temple. (WANG KAIHAO / CHINA DAILY)

Center of belief

All along the southeastern coast of China, the worship of the sea goddess Mazu shows how people expressed their hope to survive perilous voyages. Originally named Lin Mo, the woman born on Meizhou Island of Fujian province during the Song Dynasty, gradually became the main deity among seafarers setting off from Quanzhou. According to local mythology, she was able to rescue people in danger, drive away plagues, and predict the weather.

Tianhou Temple, which is located on the gateway leading to the ancient port of Quanzhou, is a key venue for people to pay homage to Mazu.

First built in 1196 as the oldest remnant Mazu temple, it was also among the highest-ranking institutions in the belief system, according to He Zhenliang, a veteran researcher of local history in Quanzhou. He was also former director of the administration overseeing the temple.

"The official sacrificial ritual has also been regularly hosted since the Song Dynasty throughout ancient China," He says. "That also shows how the state mixed folk belief to jointly promote maritime trade."

In 1329, in a Yuan Dynasty royal sacrificial eulogy, the Tianhou Temple in Quanzhou was clarified as "the origin" of Mazu belief, and He says it also marked Mazu being raised to a national-level patronage god from a regional deity.

"Spreading the belief system indicated the prosperous business here," He says. "The temple bears testimony to the development of the commercial district on the city's south side under the effects of maritime trade."

The statue of Mani in Cao'an Temple. (CHENG DONGDONG / FOR CHINA DAILY)

The statue of Mani in Cao'an Temple. (CHENG DONGDONG / FOR CHINA DAILY)

The end of the Song-Yuan era may indicate a pinnacle of ancient maritime trade in China had passed, but it is not the end of Mazu belief. Following the continuous migration from Quanzhou across the Taiwan Straits during the Ming (1368-1644) and Qing (1644-1911) dynasties, the belief system was also introduced to Taiwan.

After 1684, when Emperor Kangxi of the Qing Dynasty bestowed the honorary title of Tianhou (meaning "heavenly queen") to this temple in Quanzhou, Mazu temples were established across Taiwan.

"One temple derived from another, and so on," He says. "A complete and stratified system of Mazu belief was thus built up starting from Tianhou Temple in Quanzhou, like a tree and its branches, and the system remains a key emotional attachment across the Straits."

Following Fujian emigrants, Mazu belief also spread across Southeast Asia and even further to the rest of the world.

On Qingyuan Mountain in Quanzhou, a Song Dynasty statue of Lao Tze (Laozi), a philosopher from the Spring and Autumn Period (770-476 BC) and founder of Taoism, is seen as a symbol to reveal the rich historical context of the city. This biggest surviving Taoist stone carving from ancient China and its surrounding environment with lush vegetation is perhaps the best explanation of harmony between humanity and nature, which is a key concept of Lao Tze's ideas.

The Confucius Temple and School in the city, the largest institution of its kind in southeastern China, also witnessed how generations of ancient scholars worked hard to succeed in examinations.

"Quanzhou grew to be China's biggest port in the 12th century, and, as a window to the outside world, it represented the country's general image," He says. "Consequently, Confucianism, Taoism and other indigenous beliefs remained the mainstream in spite of cultural diversity of the city and reflected a country's willingness to display its cultural tradition."

Contact the writer at wangkaihao@chinadaily.com.cn