Streaming e-commerce has taken China by storm, fanning rags-to-riches tales across the country. But industry experts call it a boon ‘borrowed from the future’ that has rekindled bitter memories of the spectacular bike-sharing crash. Luo Weiteng reports from Hong Kong.

‘Could the show be a ‘rollover accident’?” asked Wu Xiaobo, one of China’s most successful finance writers, when he was about to make a livestream debut in July on Taobao Live — an offshoot of the country’s biggest e-commerce platform, Taobao.

“Surely, it wouldn’t be!” an assistant assured him with certainty. “We’ve ‘removed all the wheels’.”

But the show turned out to be a flop. Hopeful merchants, confident assistants and even the business-savvy writer himself, whose personal brand is built on best-sellers and annual year-end shows where Wu shares his insights into the business world, apparently under-estimated the complexity of the business logic of streaming e-commerce, and overrated his ability to sell anything from snacks, bedsheets to laundry detergents.

Yashily, a milk powder retailer, paid Wu 600,000 yuan (US$91,600) for the promotion. He managed to sell just 15 cans during the five-hour session. Three orders were canceled the next day.

Such a commercial flop may be just the tip of the iceberg in the freewheeling and loosely regulated streaming e-commerce that has been on a real tear in the world’s most populous nation this year.

With the coronavirus pandemic having roiled the entire retail industry worldwide, hastening the demise of many brands found in once-crowded shopping districts, nowhere is the potential of streaming e-commerce more apparent than in China. Elite celebrities, prominent entrepreneurs, government officials and global luxury-brands owners who might have given little thought to streaming e-commerce some time ago have now joined in the scramble to engage millions of coronavirus-wary Chinese consumers.

At the dawn of the stay-at-home economy, the boom is depicted as a lifesaver for brick-and-mortar stores to reach shoppers, a magic pill to revive the pandemic-torn economy and boost employment, as well as a new route to make a fast buck.

The craze didn’t come from nowhere. It has its roots in the energetic chaos of China’s vibrant digital economy. With its large variety of tech-savvy consumers, social media, payment processors, third-party portals, offline stores, online markets and seamlessly interactive technology, streaming e-commerce burst onto the scene as a psychedelic mashup of online chat shows and QVC-style hard-sell advertising.

“Although streaming e-commerce has been part of Chinese internet culture for a couple of years, it’s the coronavirus crisis that has essentially supercharged such a trend,” said Wang Zhentao, chairman of Zhejiang AoKang Shoes, who turned himself into a sales guru with 400-plus livestream sessions during the pandemic.

In the first half of 2020, the number of streaming e-commerce sessions in China topped 10 million. Nearly 400,000 people hosted livestream shopping events that attracted more than 50 billion views, according to the Ministry of Commerce.

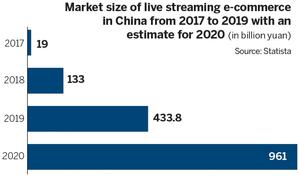

Much of the allure venturing into this world lies in the lucrative opportunities up for grabs. Nielsen predicts that by year-end, the streaming e-commerce market in China will be worth 961 billion yuan, accounting for 10 percent of overall e-commerce. The number of streaming e-commerce customers will reach 265 million, equivalent to nearly half of the country’s livestreaming audience.

“Such exponential growth can be both a boon and a curse for the new business model. Prior to the pandemic, streaming e-commerce would have taken two or three more years to become a mainstream trend. Instead, it only took two or three months,” said Pan Yuemin, a senior market insider who has been working in e-commerce for 16 years. “The growth is borrowed from the future. It overdraws the vast potential that could have made the burgeoning business a real game changer.”

“You know what? The ongoing fever really reminds me of the country’s doomed bike-sharing craze from the recent past,” Pan said.

Next tech bubble?

The meteoric rise and spectacular collapse of China’s bike-sharing sector in recent years played out like a sped-up version of every tech bubble, an unprofitable idea sustained by fantasy and the power of bigger firms.

In just a few years, the bike-sharing idea became a country-wide phenomenon. It was supposed to be the next big thing. But bloody battles for market share, unsustainable cash-burning games, and shortsighted visions turned it into another cautionary tale of “from boom to bust”.

As the bike-sharing boom went bust in the blink of an eye, no one can be sure whether the highflying streaming e-commerce will fall into the same old trap. But one thing is for sure at least — Wu was not the first and won’t be the last to learn a lesson the hard way after jumping on the bandwagon.

Shen Yi, an apparel retailer on Taobao, speaks of the lesson he learned from the streaming e-commerce mania after a few failed attempts.

“Not everyone will succeed, especially if you are just a normal, ordinary merchant with no pre-marketing,” he said.

In March, Shen paid a base fee, or “appearance fee”, of 100,000 yuan plus an actual sales commission of 7.5 percent for his products to be featured on a livestream show, for a 10-minute slot. He ended up selling 57,000 yuan worth of products. With no minimum sales guaranteed in the contract, he had no one to blame, but simply blamed it on bad luck.

The next time, Shen assembled a team of employees to hawk products live, all on their own. They fared even worse. The well-prepared two-hour livestream session attracted only thousands of views, with a few viewers placing orders.

Amidst the iconic battle call of “Buy it! Buy it! Buy it!” from Li Jiaqi, one of China’s most well-known faces of this booming trend, streaming e-commerce has all the ingredients to create a potent product perfectly constructed for viral marketing, social influence and impulse buying.

Viewers get bombarded with coupons, deals, and alerts of rapidly diminishing stock, enticing them into buying now before it’s too late. The so-called exclusive limited-number and limited-time offers intensify the “fear of missing out” and create a crazy sense of urgency to make a purchase.

Such a constant sense of urgency is also shared among clueless merchants like Shen. “When everyone nearby is looking up at the sky, you just cannot help but follow suit. Admittedly, there is sort of herd mentality,” said Liu Piaomei, a jeweler who has set her sights on streaming e-commerce since February, when 20 percent of her offline stores were closed during the pandemic.

Shen believes his failure may be a wake-up call for those starry-eyed by the industry’s intoxicating newfound wealth and overnight success.

Today, brands routinely announce hundreds of millions of dollars in sales in a single sitting. Media feed the frenzy by reporting the rags-to-riches stories of top online influencers. Viya and Li, a pair of household names in China’s streaming e-commerce circles, stand as the legendary flag-bearers. The former, hailed as “Queen of Goods”, is known for her power to sell everything — noodles, genetically modified rice, razors, houses and commercial rocket launch services. The latter made a name for himself as the country’s “King of Lipstick” by once selling 15,000 tubes of lipstick within five minutes.

Just as Viya’s live broadcast of a US$6 billion rocket launch sale on April 1 came as no April Fools’ joke, scores of people scrambled to get a seat on the rocket ship to be the next grassroots millionaire livestreamer.

Over the first 10 months of this year, more than 10,000 “gold-seekers” had made a pilgrimage to Beixiazhu, China’s “No 1 streaming e-commerce village” located in the world’s capital of small commodities, Yiwu, buoyed by another sense of urgency that “everyone is getting hilariously rich but you’re not”, according to the village’s Party chief, Huang Zhengxing.

The overcrowded market

In previous years, such a number had hovered between 200 and 300 on average.

But fortune favors the few. Only 30 percent of newcomers can actually make money. “Twenty percent manage to break even and 50 percent end up losing money,” Huang said.

The pandemic has accelerated the global trend of wealth concentration. According to data from marketing service provider Wemedia, the combined gross merchandise volume of Viya and Li reached 3.6 billion yuan, equivalent to the total GMV of the next 28 hosts.

“In terms of traffic, the gulf between the big names and everyone else becomes bigger than ever,” said Elijah Whaley, chief marketing officer of influencer marketing platform Parklu.

Pan agreed, saying “With so many merchants and livestreamers getting on board, harboring high hopes of making it big, the overcrowded market forced everyone to play the numbers game.”

Since the business rose to prominence, data fabrication is almost an open secret, bearing the imprint of the Wild West on the country’s internet scene.

Merchants and livestreamers are beholden to merciless master-instant digital metrics, said Pan, explaining how it’s tempting and possible to cheat.

The government recently warned some third-party livestreamers against using bots to inflate visitor numbers and generate fake sales to charge higher fees from merchants who hire them.

Likewise, merchants tend to fabricate data to make their online stores appear prominently on platforms and get more promotion resources, Pan said.

Zhao Yuanyuan, former president of Taobao Live, pointed out the illusion on his social media: “Now, it seems it’s not even worth bragging about if sales from a livestream session fail to reach tens of millions of dollars. The truth is many stores see 50 percent or more of their orders canceled or returned. ”

For top-tier livestreamers, a 30 percent ratio of returns is said to be normal, while for the middle tier, it could be as high as 70 percent.

As the competition for eyeballs intensifies, a relentless price war has begun, reminiscent of all the dog-eat-dog rivalries seen during the bike-sharing boom. Merchants and livestreamers feel mounting pressures to offer massive tit-for-tat discounts to fire up sales and secure customers.

In an ever-more-expensive and hostile playing field, small businesses that cannot afford to cut margins to the bone bear the brunt. “If they pin too much hope on streaming e-commerce, they’re just accelerating their demise,” warned Kan Hongyan, former vice-president of cosmetics e-commerce platform Jumei.

Lesser-known livestreamers, who simply don’t have strong bargaining power to ask brands for exclusive discounts, are also rendered uncompetitive.

Are consumers the only winners? Probably not. A study by the China Consumers Association in March found nearly 40 percent of consumers surveyed accused livestreamers of having misleading advertising and promoting low-quality or counterfeit goods.

“Some fervent believers in markets may argue such a rat race and lose-lose situation is an inevitable process every emerging industry has to go through. Yet, as the coronavirus disrupts the rhythm, letting the industry itself run rampant under all sorts of its dark arts will only spoil an otherwise great business idea,” Pan said.

“The world’s second-largest economy never lacks revolutionary business ideas. True enough. But how to make the idea a real revolution to build giant firms on, rather than a one-hit wonder, calls for a blend of delicacy and force from all parties involved.”

He believes the streaming e-commerce’s playbook is more than just one vision of retailing’s future. Its potential to lift people out of poverty by helping farmers not only from Chinese remote rural areas but also thousands of kilometers away, in Southeast Asia and Africa, to sell agricultural products is also well proven.

“Just as bike-sharing could have delivered environmental-friendly and sustainable results had it not been mired in unsustainable capital expansion, streaming e-commerce equally has more to offer,” Pan said. “As rusting relics in ‘bike graveyards’ on the outskirts of Chinese cities tell of a boom-to-bust tale, it’s time to draw some lessons and start doing real business in streaming e-commerce-before the never-ending feast comes to an abrupt end.”

Contact the writer at sophia@chinadailyhk.com