As US listings become more difficult and less attractive, mainland firms seeking a major IPO are increasingly looking to Hong Kong to provide the opportunity they need. Luo Weiteng reports from Hong Kong.

After decades of chasing the prestige of a Wall Street listing, prominent Chinese mainland enterprises that have gone public in the United States are coming home in what could be an irreversible trend that may offer a glimpse of game-changing events in the making.

Just six months after the blockbuster secondary flotation of e-commerce behemoth Alibaba Group in Hong Kong, two of its tech peers — Guangzhou-based NetEase, which went public in the US in 2000, only to be delisted from the Nasdaq the following year amid allegations of fraudulent corporate practices by its directors and listed on Nasdaq again in 2002; and Beijing-based online retail giant JD, which has a slot in the Fortune Global 500 — have made a solid debut in Hong Kong, with a slew of mainland businesses likely to follow in their footsteps.

As of June 19, 33 Chinese mainland enterprises have gone public on the Hong Kong Stock Exchange this year, raising US$10.1 billion in total.

“To be sure, the homecoming of US-traded mainland firms is nothing new,” said Li Songze, chief investment adviser at Chuancai Securities.

The nudge to trek back to home turf was probably nurtured in 2011 as a growing number of Chinese mainland enterprises companies got delisted in the US amid stringent regulatory curbs, short-seller attacks, and the failure of foreign investors to adequately value them.

Another wave of delistings followed in 2015, including the high-profile privatization deals of security software specialist Qihoo 360 and online game developer and operator Perfect World, both of which embarked on the long, hard road back to a domestic listing.

The impetus for the fresh bout of homecoming remains as old as time. But it comes at a delicate moment as the decoupling of the world’s two economic superpowers hit a crescendo over a host of economic and geopolitical issues. It may also be too late for Chinese mainland enterprises to look back with regret, with the Nasdaq — the ultimate dream of the tech creme de la creme — making spectacular advances over the past two months as investors try to put the worst of the coronavirus shock behind them.

The accounting infamy involving Beijing-based Luckin Coffee, which burst onto the scene in 2017 as a high-profile answer to US beverage titan Starbucks, dropped a bombshell that spawned a “trust crisis” in which even US-listed mainland firms boasting a sound financial or property label found themselves embroiled in.

In a rare move, US Securities and Exchange Commission Chairman Jay Clayton warned in April against investing in Chinese firms. A bill that the US Senate passed in May calls for stricter audit standards for for- eign companies, and could potentially force many Chinese firms to ship out their listings elsewhere if the US House passes it and US President Donald Trump then signs in into law. In addition, the Nasdaq’s new curbs on IPOs will certainly make it harder for some Chinese companies to make it to its bourse.

“Once again, US-listed Chinese companies have run into a hostile climate in New York,” said Pan Xiangdong, chief economist at New Times Securities.

As the mounting regulatory scrutiny and new IPO restrictions mark just the latest flashpoint in the lingering Sino-US political rhetoric, “the ongoing homecoming may not be a flash in the pan as before, but has what it takes to become the norm in the near future”, Li said.

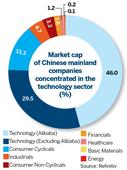

Statistics from global financial market data provider Refinitiv showed 409 Chinese mainland enterprises are currently listed on US stock exchanges, accounting for 3 percent of the total market capitalization. By market cap, 76 percent of the US-listed Chinese mainland companies are from the technology sector, with Alibaba taking up 46 percent overall, followed by consumer cyclicals with 13 percent.

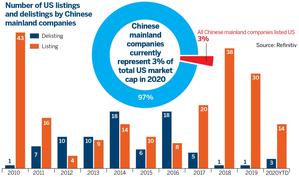

Up to June 16, 14 Chinese mainland companies have successfully listed in the US this year, which pales in comparison with 30 in 2019 and 38 in 2018. During this period, as many as three companies were delisted, including gaming company Changyou and online cosmetics retailer Jumei, whose high-profile founder, Chen Ou, was crowned the youngest publicly-listed CEO in China in 2014.

“There’s a downward trend of Chinese companies getting listed in the US,” Refinitive said.

Unlike their delisted peers which might see delisting as a last resort with much reluctance years ago, the new batch of US-traded Chinese mainland firms are today making a beeline for home in a more proactive manner — they’ve more suitable places to go to.

Open door to overseas firm

Optimism over a domestic listing has risen on hopes that market overhauls by Beijing will make the once-complex and time-consuming listing procedures, entangled in red tape, simpler and more efficient.

Chinese mainland securities regulators and stock exchange officials are making a fresh attempt to attract technology listings, with the launch of a sci-tech innovation board in Shanghai last year, the newly amended securities law this year, and the ongoing registration-based reform on Shenzhen’s ChiNext startup board.

They’ve wasted no time having the door wide open for innovative companies with weighted voting rights (WVR) and pre-profit firms, which could pave the path to tech glory for exchanges.

“Basically, the historic overhauls have helped US-traded mainland companies grind out the last mile on their home journey. Their homecoming is a big trend that cannot be reversed,” Pan said.

But Hong Kong appears to be one more step ahead. The Asian financial center introduced its biggest listing reforms for 25 years in April 2018, upping the ante in its competition with New York for the highly sought-after new-economy and biotechnology listings.

The reforms have opened the gateway for companies from emerging and innovative sectors with a WVR structure and biotech companies without any track record of revenue or profit. It also provides a concessionary secondary listing route for Chinese mainland and international innovative companies listed on qualifying exchanges overseas.

The sweeping changes dismantled the hurdle that caused Hong Kong to lose out on Alibaba’s US$25 billion deal in 2014 — the world’s largest IPO.

In November, Alibaba — by far the largest US-listed Chinese mainland corporation in terms of market capitalization — made its US$13 billion Hong Kong debut with a secondary offering. The mega float, which Alibaba CEO Zhang Yong described as a “homecoming”, represented a vote of confidence in Hong Kong in the midst of months of violent anti-government protests.

In a sign of the city bourse’s determination to welcome back “homesick” mainland firms listed overseas with open arms, the 50-year-old benchmark Hang Seng Index announced in May its biggest reform in 14 years. The gauge, along with the Hang Seng China Enterprises Index, will admit Chinese mainland companies with a WVR structure and those with secondary listings as constituent stocks.

With both A-shares and Hong Kong markets shaping up as viable rivals to Wall Street in the race for the new economy’s IPO crown, Steven Yang Lingxiu, chief strategist at Citic Securities, believes Hong Kong is fully capable of being the “go-to” destination for US-traded mainland firms seeking a foothold closer to home.

Hong Kong’s current listing regime allows companies to maintain the existing variable interest entity (VIE) structure to go public, Yang said. The VIE structure is used as a method for mainland domestic entities to gain access to international capital markets through offshore listings, and enables foreign investors to indirectly invest in restricted or prohibited sectors on the mainland.

US listing not top option

“Although Shanghai’s sci-innovation board and the reformed Shenzhen’s ChiNext startup board have also set the stage for VIE-structured companies, the bar remains relatively high and rules have yet to be tested,” Yang wrote in a recent research report.

In fact, Hong Kong’s streamlined listing process has put mainland companies listed overseas on the fast track for a planned Hong Kong float. “It takes roughly three months to get all the preparation work done,” said Edward Au, Deloitte’s co-leader of the national public offering group. “Certainly, the homecoming of US-traded mainland firms will be the focal point for the Hong Kong stock market in the second half of 2020.”

Once a badge of honor among Chinese enterprises, a US listing offers greater control for founders, a higher degree of liquidity and trade and, above all, prestige, although their tales may be a bittersweet ballad of love and hate.

Today, much of the advantage is on pace to be wiped out. A US listing should no longer be the alpha and omega for a Chinese company, said Wu Wenjie, former chief financial officer of mainland online travel agency Trip.com.

The SAR’s long-cherished attractions, including well-developed capital markets without any capital control curbs, coupled with strong legal, regulatory and financial regimes with easier access to international investors, make the city an ideal listing venue for mainland companies seeking to exit the US stock market or explore alternative avenues to raise funds.

And then of course there’s Hong Kong’s proximity to and close links with the Chinese mainland that ensure seamless collaboration between cross-boundary regulatory authorities and stock markets.

“Companies may further mull a domestic listing after it has established a presence in the Hong Kong market. This remains a possibility,” Wu said.

“In turn, the homecoming of US-traded mainland firms will help reshape Hong Kong’s stock market, which has long been dominated by the traditional real-estate and financial services sectors,” Yang said.

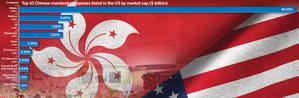

As many as 39 US-traded Chinese mainland firms are believed to have the potential for a secondary listing in Hong Kong, according to Refinitiv. The top 10 US-listed mainland companies by market cap are on the list. However, e-commerce behemoth Pinduoduo — by far the second-largest mainland corporation listed in the US by market capitalization — denied market rumors that it plans to float in Hong Kong in July.

“In the past few decades, China’s economic and technological miracle has given birth to a whole breed of entrepreneur-led enterprises. Though the country is home to the largest online community on Earth, most of its symbolic internet enterprises have chosen to list overseas. This doesn’t fit in with the ever-changing development of the world’s second-largest economy,” Li said.

“From this point of view, the homecoming of mainland firms listed overseas is a historic certainty, as high-tech and modern industries become our next growth engines. US-traded companies from these sectors cannot afford not to gain a foothold closer to the home market and target consumers,” he said.

“But, more importantly, with a listing at home, it’s time to let Chinese people share the huge development dividends these companies have long enjoyed since they timed the take-off with the meteoric rise of our nation’s economy.”

Contact the writer at sophia@chinadailyhk.com